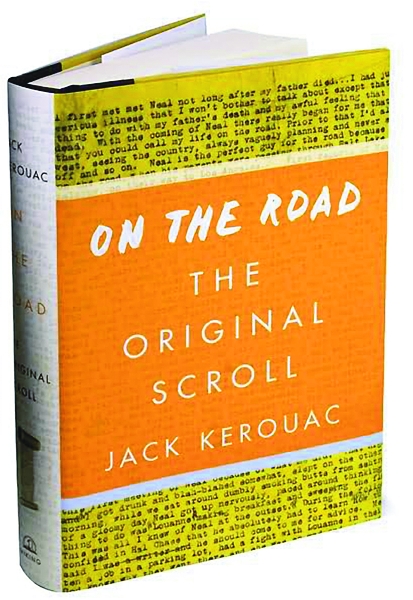

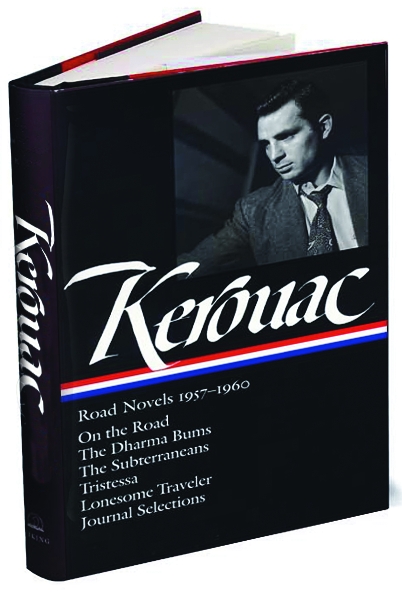

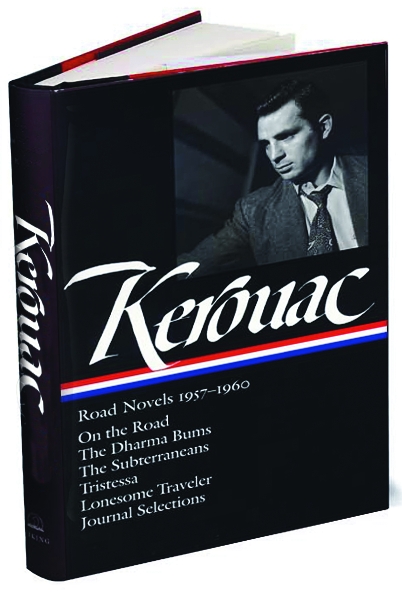

Shot Of Jack

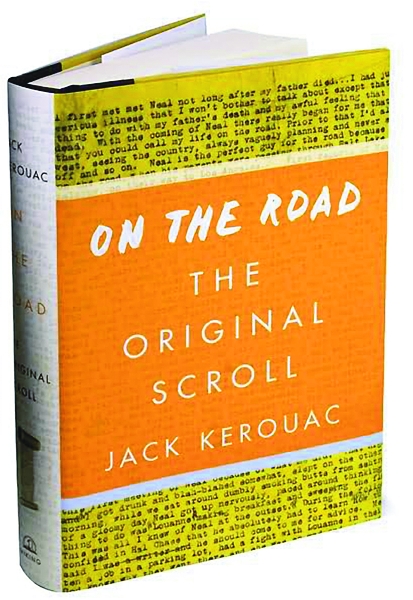

Kerouac's On The Road Hits 50

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992