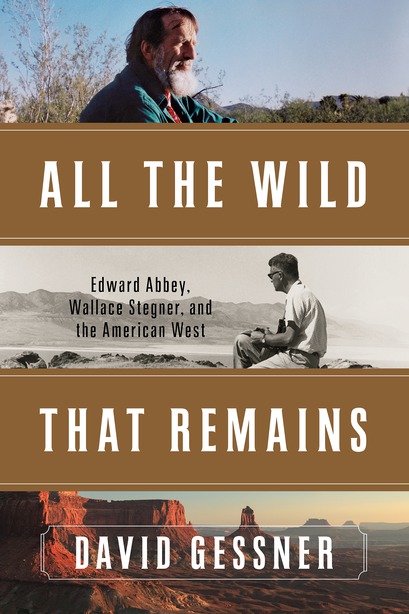

Book Review - All The Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, And The American West

Book Review - All The Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, And The American West

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992