"Wednesday We’ll Go Back to Class"

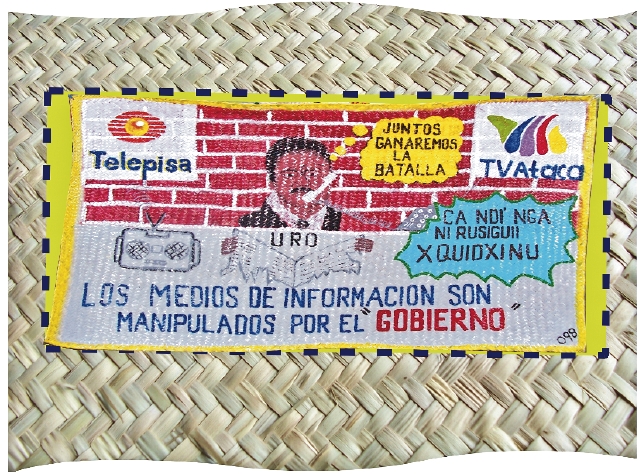

Meyer was in the encampment on June 14. At 4 a.m., state police moved on the camp of teachers and their families. "I was scared," she says. "I’ll be honest."But let’s start at the beginning: The teachers of Oaxaca began their strike on May 22, occupying the zocalo , the center of the city’s Downtown. Oaxaca, like many Mexican cities, has a heart of pretty tourist areas surrounded by miles of intensely impoverished neighborhoods. As the town’s tourism industry boomed, the price of real estate and services increased. The teachers wanted a pay hike, as well as better conditions for schools, among other things. Ryan Judge has seen the trouble firsthand. "Schools might have the building, but they don’t have water; or they have classrooms, but the desks aren’t put together because they’re broken," he says. Teachers were also requesting breakfast and lunch programs for students. Judge, who is studying for his master’s in Latin American Studies at UNM, lived in Oaxaca from 2000-2005. He was also there this year from May until August. During his time in the city, he witnessed six teacher strikes, some of which he attended. Many of his friends are teachers. "Usually, the strikes are two or three weeks." The teachers camp out in the zocalo . "Sometimes you might have 20,000 people living there," Judge says. Strikers bring their families. Often, demonstrators close the main arterial roads going in and out of the zocalo , or block off banks, government buildings and stores. "That irritates a lot of people," Judge says. "Sometimes, when the teachers start to become mobilized and start the strikes, people will say, ‘These people are just bothering us. We don’t like them.’” This year, Judge says, the strike almost didn’t happen. "Monday of the first week of the strike, teachers said, ‘OK, symbolically, we’ll go on strike today. Tuesday we’ll sign the contract, and Wednesday we’ll go back to class.’” Negotiations broke down. Gov. Ulises Ruiz, accused of stealing the election that put him into office in 2004, began using TV and radio to promote his message. "They would have little kids chanting slogans, like, ‘Us children, we want classes. We don’t want strikes,’" Judge says. The state government also began circulating rumors that there were armed groups of troublemakers within the teachers’ movement, Judge adds. That rumor was used as justification for the June 14 raid that turned the teachers’ yearly strike into a broad social movement with implications for the entire country."Four in the Morning, The Word Came"

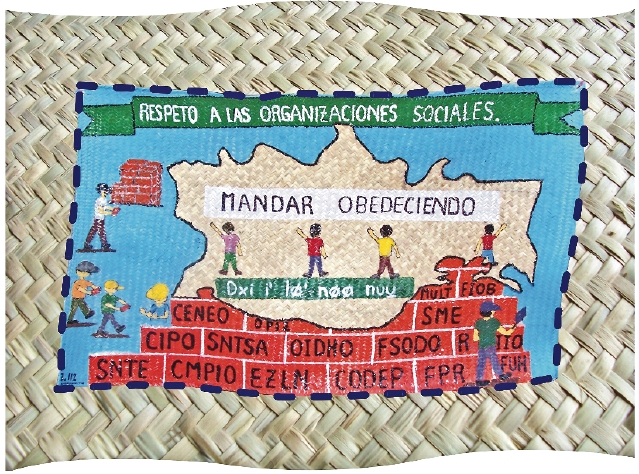

The state police raid on the encampment violated some of Mexico’s political norms, according to Judge. Usually, before police enter and protesters are kicked out of Oaxaca’s square, police give a 15-minute warning, enough time for some of the demonstrators, including women and children, to leave. "In this case, that didn’t happen."Meyer remembers well the night she chose to stay in the camp (called the planton ) that at the time occupied more than 40 city blocks, she estimates. "There were probably between 30,000 and 40,000 sleeping in cardboard, under those awnings, covering the center of the city on any given night," she says. She’s worked with a coalition of more than a thousand indigenous teachers in Oaxaca for seven years. She reached the city in early June to continue workshops that help the teachers develop materials in their languages. Since all of the teachers were in the planton , she decided a deviation in the standard workshop plan was in order. "Looking at their reality and the encampment and their strike and the stress, tension and tiredness—even at that time—and listening to them. They said their concerns were that the city of Oaxaca and the people of Oaxaca understand what the strike was, and that their communities understand why their teachers left the classrooms."Work began immediately on banners (see above), 24 paintings on large straw mats called petates usually used to sleep on. The paintings explore the causes of the strike and the teachers’ hopes for its outcome. All but five were burned the night the police came, though Meyer had taken photos of them all. She asked the teachers if she could stay in the camp one night, so she could "more deeply experience" their struggle. There had been rumors of police action for days, she says, so it wasn’t a small request. "They were risking themselves," she says. "If anything happened to me, they would consider themselves somewhat responsible."At about 11 p.m., word-of-mouth suggested a possible police raid. Scouts reported no movement. Everyone settled back down in their bedrolls. "The government used these rumors of repression to instill fear, and it worked," Meyer says. "I noticed how confident the teachers seemed. They’d been through so much. We settled down. About four in the morning, the word came that, indeed, the encampment was ringed by the state police."Leaving their belongings behind, thousands began to move as orderly as possible along the escape route, trying to get to one of Oaxaca’s famous churches that offered safe haven. Demonstrators held cloth over their mouths, soaked in alcohol or water, intended to cut down on the effects of tear gas, which was expected. The law school opened its big colonial door unexpectedly, and hundreds entered. Women and children were moved out of the courtyard and into the classrooms. "The police in Mexico have a grim history of rape," she says. Hours passed. The strikers resisted the police and retained control of the city’s center. Meyer concludes the tale of that night with tears in her eyes: “We knew somebody was coming for us. We didn’t know if it was police or if it was teachers coming. When they opened the door and said, ‘go out’—everybody was expecting tear gas—we didn’t know what we were expecting. We went out, and it was the most amazing experience to walk out of that building and see the street full of teachers, who were just cheering us, many of them with their faces covered, assuring us that everything was OK. They were in charge of the streets, and we should just exit. Women with children and babies and also men—it was an amazing thing. We walked for blocks …”"Well, Yeah. We Cheated"

G ov. Ruiz’ move to stamp out the blemish on his city by sending in state police spurred the anger of other movements in Oaxaca. The People’s Popular Assembly of Oaxaca (APPO), a coalition of many civic groups, was born on Saturday, June 17. The demand changed when the APPO formed. The strike was no longer about only classrooms and teacher pay. Ruiz, a brute and tyrant, the APPO demanded, should step down. The APPO joined the teachers in the zocalo , the numbers of occupants swelling to unknown proportions. To remove a governor legally, according to Judge, you have to show that he’s lost control of his state. "If Congress at a state or federal level, or the president, say you’ve lost control, you’re no longer the governor," Judge says. The APPO began building roadblocks, he says, took over radio and TV stations and municipal governments throughout the state. The loss of control became an embarrassment for the governor, but corrupt politics and the power of Mexico’s oldest political party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), kept Ruiz in office."A lot of the people at the federal level have argued, ‘We can’t get rid of this governor, because if we do, other states will realize that if you rise up, you can throw out the governor, and that’s not in our best interest.’”Still, some teachers have grown restless in the state, as the school year usually ends in early July and resumes in early August. They’ve missed weeks of class, and so have the state’s 1.3 million students, reports the Washington Post . On Thursday, Oct. 26, 31,000 members of the teachers’ union voted to end the walkout. Some schools had already reopened. Perhaps sparked in part by the death of American photojournalist Bradley Will in Oaxaca on Friday, Oct. 27, and increasing pressure from the global community, President Fox sent in thousands of federal troops to retake the city’s center on Sunday, Oct. 29, with water cannons and tear gas. In the days that followed, the protesters showed that they would not be beaten back so easily, and on Sunday, Nov. 5, people from around Mexico traveled to the city to march and demand the exit of the federal police. Estimates put the crowd at 20,000. As of Monday, Nov. 6, Gov. Ruiz refused to bow to the ever-louder cry that he leave his post. Rebeca Jasso-Aguilar was born in Mexico City and lived in the country until a few years ago. She’s been protesting outside the Mexican consulate in Albuquerque along with a handful of others, including Judge and Meyer, beginning Monday, Oct. 30. The protests culminated in a larger demonstration with Albuquerque’s teachers and a discussion with the consulate on Monday, Nov. 6. The hope, says Jasso-Aguilar, Judge and Meyer, is to show that these events are on the minds of people in the United States. Jasso-Aguilar attributes the strife in Mexico to a growing feeling of helplessness due to the corruption in the electoral process. "We suddenly realized all the institutional methods for change disappeared," she says. "But it was so open. It was so shameless. It was like seeing the powers that be, the ones that committed the fraud, saying, ‘Well, yeah. We cheated. We did this. We did that, and we got caught. What are you going to do about it?’" What now? asks Jasso-Aguilar. How can the people of Oaxaca create change if all the usual channels are closed to them? "People take to the streets when they have no other choice," she adds. The Oaxacan movement transformed from a teachers’ strike to a powerful democratizing demand, says Meyer. Reports from her friends who are still in Mexico say APPOs are organizing in other states. "I think there’s a good chance that if the Mexican government doesn’t open its eyes very quickly and deal seriously with these issues, it could have a major, major upheaval on its hands.”Oaxaca Timeline

Fund-Raisers And Solidarity Actions For Oaxaca

To contact the author, e-mail marisa@alibi.com.