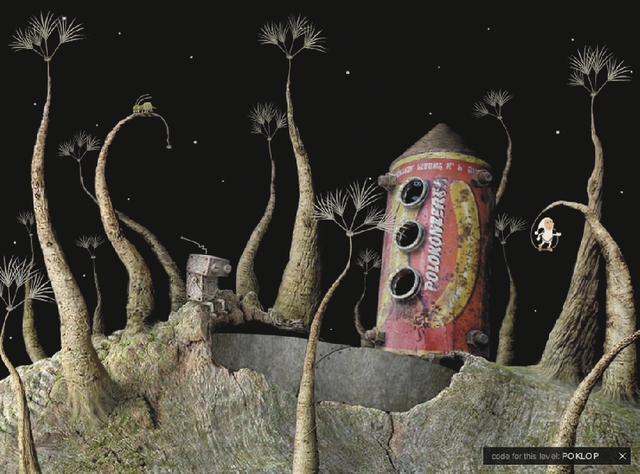

"Art games are to the game industry what short films are to the film industry."—Julian OliverArtists are working with a new medium: videogames. In a way, they’ve been at it since the early ’70s. While Atari’s PONG (1972) didn’t exactly presage the idea that videogames could be art, even prehistoric text-only computer games like Hunt the Wumpus (also 1972), in which the player tracks a fierce beast along the vertices of a dodecahedron, exhibited a geeky flair for leveraging CPU cycles to produce imaginary environments.In 1983, the soon-to-be father of virtual reality, Jaron Lanier, produced the interactive music game Moondust — arguably the first full-blown "art game"–for the Commodore 64. The bleepy ambient score that emerges during gameplay is as abstract and compelling as any modern blip-hop release. The same year, Atari released programmer Dave Theurer’s I, Robot, a game so full of new ideas (the first with 3-D polygon graphics and camera control) that ’80s arcade-goers were baffled. Most significantly, I, Robot featured an "ungame" mode called Doodle City wherein players can paint with static or rotating elements from the game and produce their own videogame art.In 2001 (we’ll skip the CD-ROM-obsessed ’90s), Sega released Tetsuya Mizuguchi’s Rez for Dreamcast and PlayStation 2, a traditional on-rails shooter with an incredibly innovative presentation: A pulsing techno soundtrack evolves as the player progresses, the force-feedback in the game controller throbbing in time to the beat of the music. The wireframe graphics, which harken back to the Disney film Tron (1982), intentionally reference both Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky and the visions produced by psychedelic drugs. The net effect is ecstatic and transcendental, yielding an experience as close as possible to the "synesthesia" the creators explicitly cite in the game’s attract mode.Now, with new tools (programming kits, graphic libraries) and a ubiquity of avenues for distribution (Web-based games, console downloads), current art games run the gamut from point-and-click Flash projects like Samorost (1 and 2)–kid-friendly puzzle games with a moss-grown organic style and sly, dark humor–to Jenova Chen’s meditative works Cloud and flOw. In Cloud , inspired by dreams of flying, the player manipulates clouds and releases them strategically to build huge cloud sculptures or thunderheads. In flOw (now available for PlayStation 3) you control an evolving (or devolving) creature in a 2-D plane, gobbling everything in your path and choosing blue or red globs to rise or fall within the Z axis of some primordial soup. Games like these are becoming more common. Electroplankton for the Nintendo DS and even sleeper PS/2 hit Katamari Damacy qualify. Some promising art games are still vaporware, including the Rez-inspired Everyday Shooter (described as an "album" of games) and the Wii "casual ambient" prototype Pollen Sonata, in which the player controls a pollen cluster navigating a fully 3-D world of gargantuan flowers. Given the growing discourse on videogame innovation (google it), we could be on the verge of a sea change in game design.

"If you grow up with something … if it’s a part of your everyday life, you’re gonna make art about it."—Cory ArcangelThe flipside of art games is game art: art produced using videogames as the medium. The end result can be anything: film, music, installation, artifact or a videogame mod that subverts the original game.In 2002, Brooklyn artist Cory Arcangel modified a Super Mario Brothers cartridge to create Super Mario Clouds, a version of the game from which everything was erased except peaceful scrolling clouds. This project paved the way for other game cart hacks (F1 Racer without the cars, Space Invaders with only one invader and a 15-minute Super Mario film). In 2004 his work was featured in the Whitney Biennial exhibition, thus cementing its acceptance as "real" art.Game artist Julian Oliver (also ringleader of the essential game art website Selectparks.net) says artists need to "reclaim games as a medium for any use, not only ‘entertainment,’" and he has a multitude of projects supporting this dictum: Qthoth , a Quake II mod that turns the shoot-’em-up game into an interactive sound and vision generator; Second-Person Shooter , a virtually unplayable Quake III mod where you see your opponent’s view and he sees yours; and ioq3aPaint , where Quake bots run rampant with paintbrushes tied to their virtual tails and produce–what else?–art.The term "machinima" describes films created using game engines like Quake or Unreal Tournament. The Internet is chock-full of examples, ranging from level speed runs to sitcoms like Red vs. Blue. But not all machinima must feature men with guns. In 2006 a French Trackmania enthusiast called BlackShark released "1K Project II," now viewed more than a million times by a global audience. Using the game’s replay editor, BlackShark ran the same course 1,000 times in 1,000 different cars, then produced a surreal machinima film by playing back the 1,000 runs simultaneously. The result is a swarm of automobiles cascading like water from absurd jumps and collisions (when asked what she was watching, my 3-year-old said, "It’s fish! It’s a like a rainbow!"). BlackShark’s editing and virtual camerawork distinguish this exhilarating piece from the hordes of imitators (3,000 cars! 4,000 cars!) and it still stands up.“Sonichima” or "chiptunes" are terms for music created using videogame hardware. The recent (February 2007) release of 8-Bit Operators, a collection of Kraftwerk covers produced by 8-bit artists using Game Boys and other archaic gear is perhaps the most public achievement of the movement, but artists like Bubblyfish and Bit Shifter have been producing music with these tools for several years.Videogames have become such a large part of the cultural landscape that they are now raw material for art and commentary. DJs have been plundering the media archives of prior generations for years now, producing challenging new mutations. Now videogame artists have the same kind of history to build upon. Art games and game art are two vectors of this new movement. One sign of change: Jenova Chen’s company now has a three-game deal with Sony. Interesting times lie ahead.

You can view the author's own experiments in "expanded machinima" at www.macmountain.org/pixielation.