Best Western: The Comeback Of The De Anza Motor Lodge

The Artistic History And Impending Comeback Of The De Anza Motor Lodge

This is how the De Anza’s western face may look some day.

A rendering of the De Anza’s Central elevation by Integrated Design & Architecture

Integrated Design & Architecture

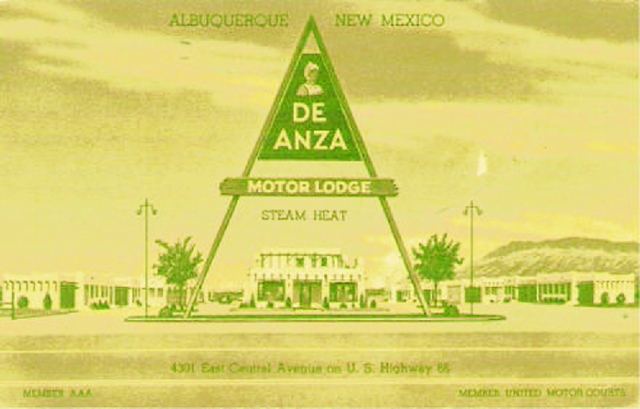

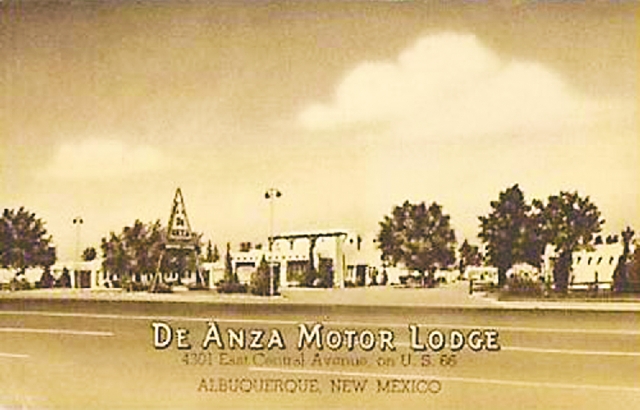

’40s era

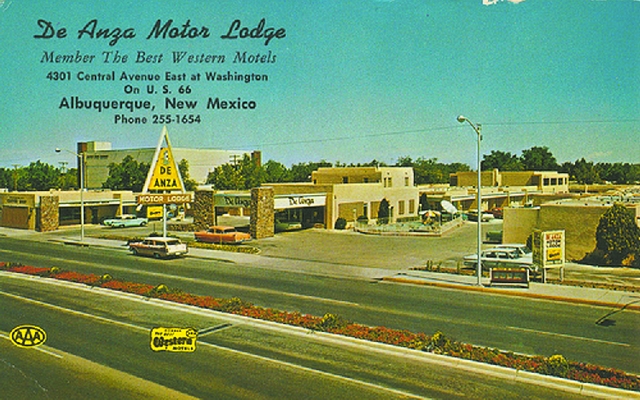

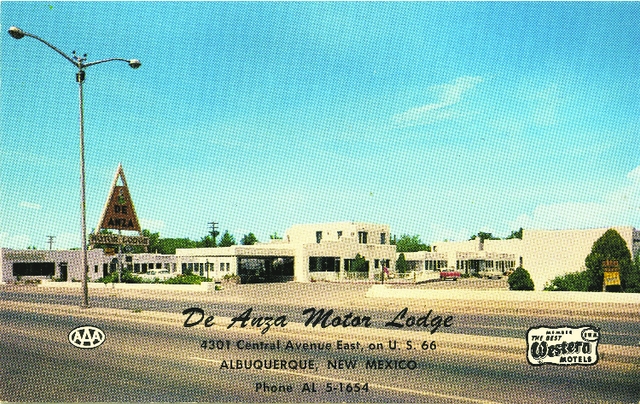

’50s era

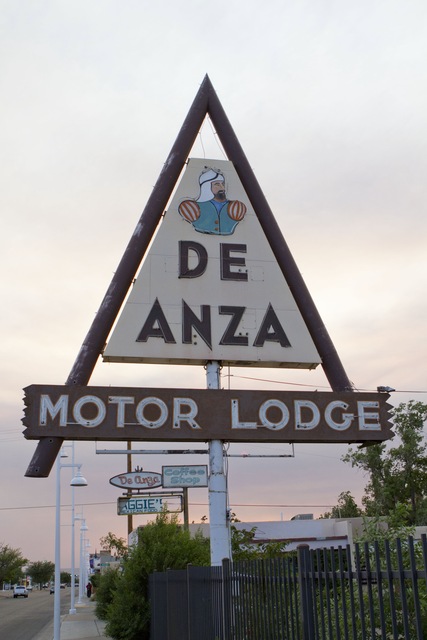

The motel today

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com