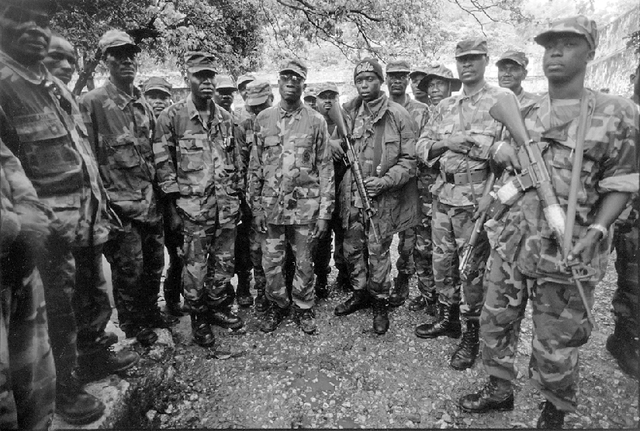

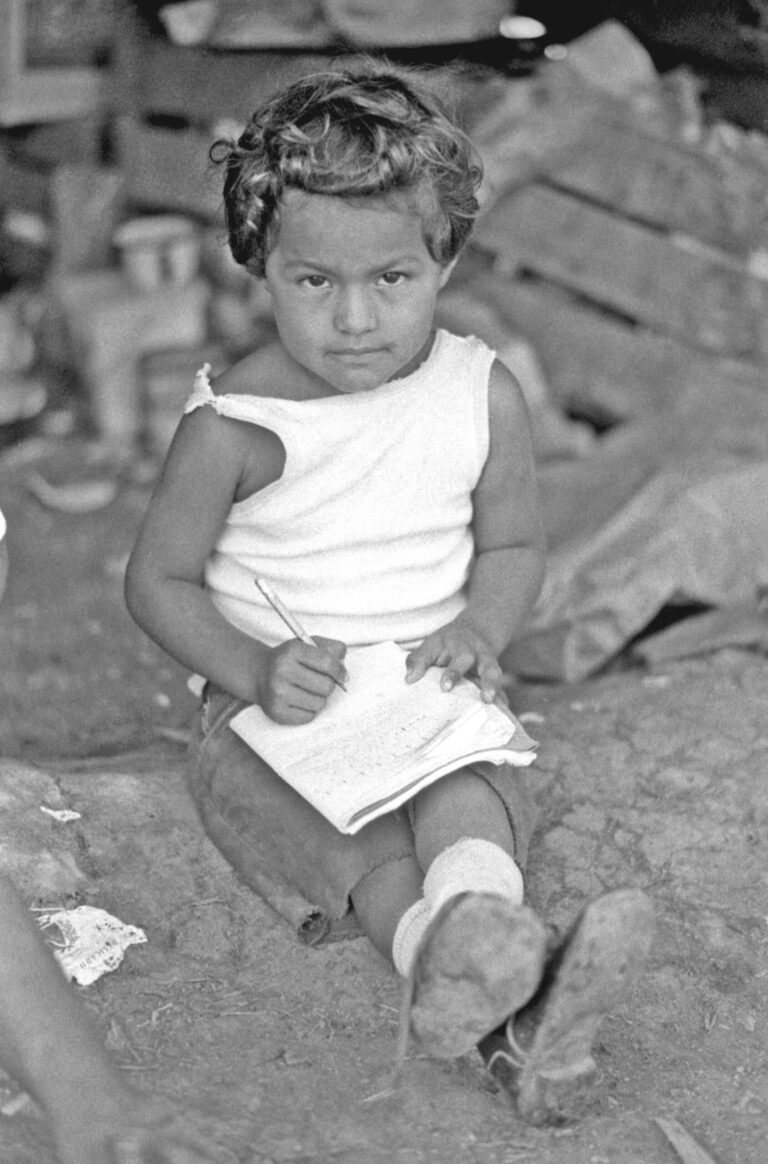

It’s like dancing with somebody, taking a picture, says Alan Pogue. "If the photographer is rigid, it doesn’t work. You have to move with the other person. What they do has to influence what you do." Vision, he says, is touching at distances.Pogue is speaking from his home in Austin, Texas, where he lives with 300,000 negatives in five fireproof filing cabinets, each of which weighs more than a Volkswagen. "My house could burn down twice," he jokes. He’s not taking any chances with his life’s work, 38 years of photography documenting liberation movements in the U.S., farmworkers, strife around the world, prison conditions, protests, campaigns. He’s worn out his passport and had pages added to it. "When I reflect on how big the world is, it seems like I’ve hardly made a dent."When he was heading to the Vietnam War where he would work as a medic and chaplain’s assistant, his mother gave him a Kodak Instamatic. "She said, Send some pictures, because I know you won’t write a letter," he remembers. As a medic, he could give his film to the helicopter pilots along with his requests for medicine and bandages. "I was getting immediate feedback," he says. "I was seeing war close up as a medic, and I was seeing the destruction and how much we were hurting the Vietnamese people—blowing up the countryside, shooting the water buffalo and dropping napalm on people. It was pretty darned disgusting," he says in his slow, quiet cadence. "I was taking pictures, and I was having my whole worldview trashed." The Big Picture The overwhelming truth, says Pogue, is that most people really like to have some attention paid to them. "Everybody’s got a story, and everybody wants to tell it. And if you listen, they’ll tell it." One shot in particular stands clear in his mind. He was documenting 300 Mexican farmers in 1980, landless people who had a legal claim to the acres they were squatting on. "They camped out. They started tilling the soil. They started planting crops." They lived in tents and other shelters made of tree limbs and scraps. One morning at 6 a.m., Pogue was watching the adults cook breakfast over an open fire using a piece of sheet metal. A child was sitting nearby using a Big Chief writing tablet to practice the alphabet. "I took one picture, and the little kid looked up at me. I took another picture, and that was the one, because he looked at me with the most serious expression."The mistake some photographers make is that they think their job, taking pictures, is more important than the person they’re taking pictures of, says Pogue. "They’re so into whatever they’re doing, they don’t pay enough attention to people." Add to that a media that values the shocking, the scandalous, and you’ve got an American audience that almost never sees the big picture. "I’ve seen some books done on Haiti, and everybody focuses on voodoo." That stereotypical depiction is inaccurate, he says, because vodun’s part of the country, but not everyone’s involved in it. "That’s the part of photography that drives me crazy. It’s pseudo-reality. They focus on what sells, and voodoo sells."Though he saw plenty of intelligent, hardworking people in Cap-Haïtien, Haiti, Pogue also found himself in a photo-taking situation that caused in him the most fear he’s ever felt, he says. He was in the city in 2004, right after the coup when President Jean-Bertrand Aristide was forced to leave the country. Pogue was working for the National Lawyers Guild, which was investigating the murders of hundreds of Aristide supporters. An interpreter, a lawyer and Pogue went to speak with a group of 130 heavily armed rebels that he says had burned the mayor’s house down and taken people for ransom. "They could kill us, and nothing would happen to them. Who’s going to do anything about it?" Pogue wondered as they drove to the address. Killing North Americans might be bad press, "but on the other hand, how bad? For them?"The thing that saved them, Pogue says, was that the man in charge was vain. "He wanted to have his picture taken. He thought it would be cool." Normal Life Goes On That was a really up-front, face-to-face kind of fear, Pogue says, different than when he was in Baghdad during a missile attack. Or when he photographed a man sitting in the Rio Grande between Mexico and the U.S. shooting people up with an unknown substance. Or that time he had to run from the police in Matamoras, Mexico, after taking pictures of polluting chemical plants. "I’m almost always photographing as an advocate," Pogue says. "I’m not disinterested. I do want prison reform. I do want there to be an end to war and conflict. The pictures I take, I don’t think of them as a commodity. I don’t think, Well, this is a great stock photo. I’ll be able to sell it to this, that and and the other publication." Viewing all of the unjust, human-caused, global pain can get under Pogue’s skin at times. "When I’m in the middle of it, I tend not to think about it and just act. When I’m back in Austin and able to reflect, it often makes me extremely sad." A lifelong interest in philosophy helps him cope. Still, when choosing photos for his first solo book, Witness for Justice , Pogue strove for balance. "I sat down with a legal pad to make a list. I don’t want to show just destruction. I wanted to show beauty and humanity, and the fact that normal life goes on."There’s a political economics for the art world, and documentary photography is on the low end, Pogue says. The tastemakers in Manhattan prefer the kinky, psychologically twisted and the unreal to photos that examine how the world works. "No one’s connected to anything, no cause is being advanced," he says. "It’s art about art—very alienated. And alienation becomes a commodity."Even in the documentary art world, some photographers’ work suffers from a lack of feeling. "It’s like somebody being sick, and you take a beautiful picture of them. Well, great! But where’s the medicine? How are we going to cure this person?" Like a moth to a flame, photographers flutter toward the money, and sex and violence pays, he adds. "If a person really does care, then they have to try and tell as much truth with as much depth as they can manage—and then not shy away from drawing conclusions and making recommendations."

Hear Alan Pogue speak about his photography and his activism Wednesday, March 26, at 7 p.m. on UNM Campus in the Mirage-Thunderbird Room. The event is free. Also, the public is invited to attend two lectures by Pogue at UNM through the Peace Studies Program at 9:30 a.m. in Dane Smith Hall, Room 328, and again at 11 a.m. in Dane Smith Hall, Room 132.Pogue will sign his book Witness for Justice at Barnes & Noble in Coronado Mall on Thursday, March 27, at 7 p.m. He will also attend an author reception and book signing at Verve Photographic Gallery in Santa Fe at 219 East Marcy Street from 2-4 p.m. For more info, call (505) 982-5009 or go to www.vervefinearts.com.To see more of Pogue's work, visit www.documentaryphotographs.com.