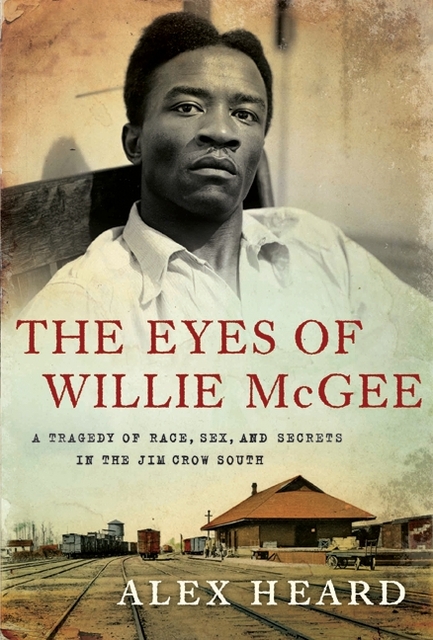

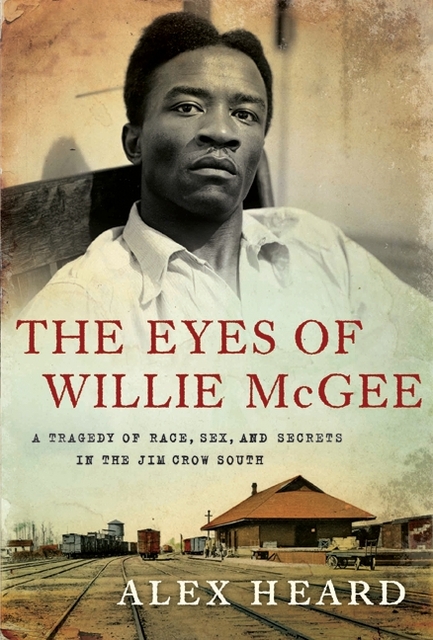

Book Profile: Alex Heard Goes Back In Time To Re-Examine An Infamous Court Case

Alex Heard Goes Back In Time To Re-Examine An Infamous Court Case

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992