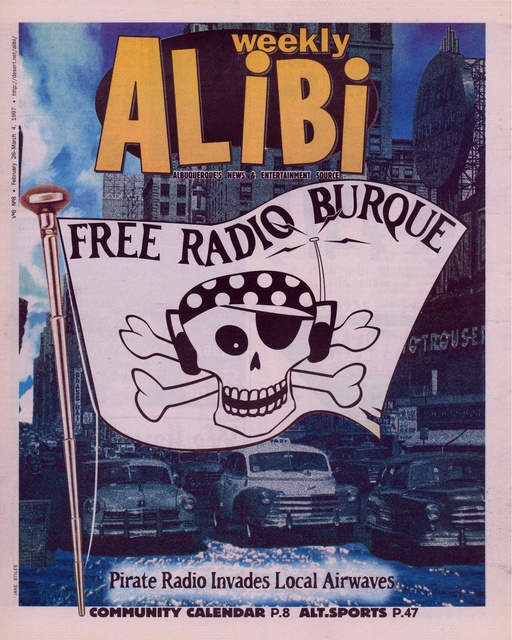

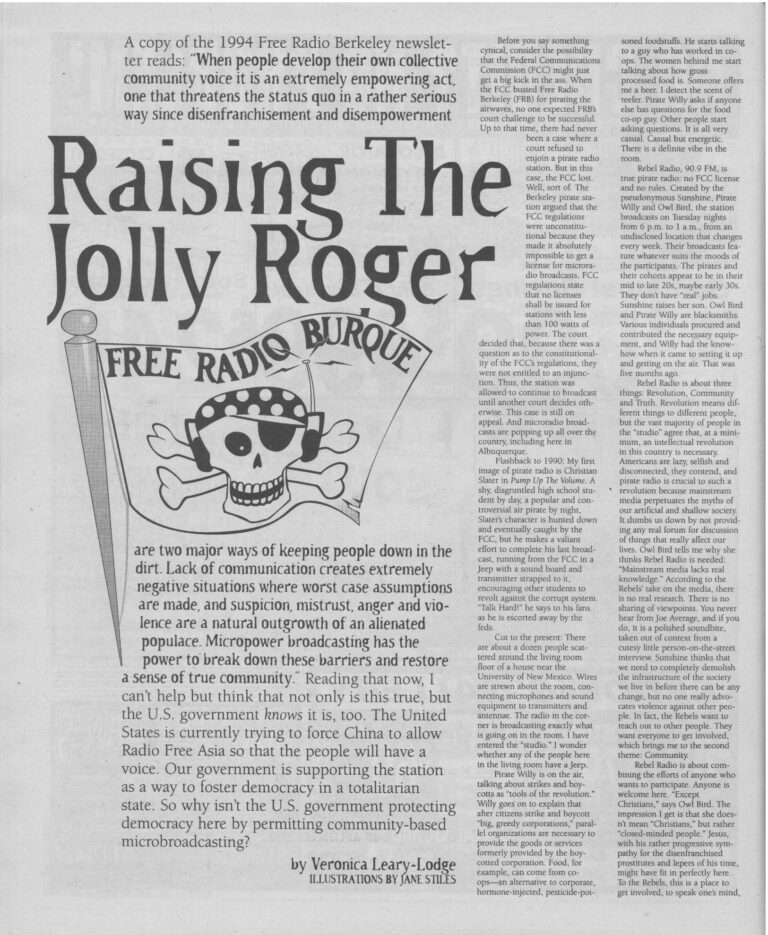

Free Radio Burque: 1997 Rebel Radio Story Unearthed

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992