Happy In Their House In Spite Of Hoops And Hurdles, These Moms Built A Stable Home

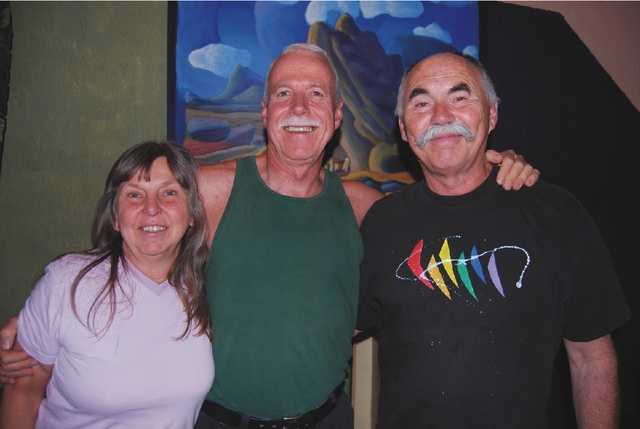

Danae, hangs out with her moms DeAnna and Rebecca, left to right, and her kid sister Madison on UNM campus.

Xavier Mascareñas

Danae, hangs out with her moms DeAnna and Rebecca, left to right, and her kid sister Madison on UNM campus.

Xavier Mascareñas

Xavier Mascareñas

Xavier Mascareñas

Mommy And Mimo Loving Parents Get Plenty Of Support From Family And Friends

Taylin (left) was on her best behavior during the family’s interview with the Alibi .

Xavier Mascareñas

Taylin (left) was on her best behavior during the family’s interview with the Alibi .

Xavier Mascareñas

From left to right: Taylin, B.J., Kelly and baby Teagan

Xavier Mascareñas

From left to right: Taylin, B.J., Kelly and baby Teagan

Xavier Mascareñas

A Long Night's Journey Into Day From Closeted Kid To Proud Grandparent

"Coming out is not something that just happens once," Julian Spalding says. "It happens over and over and over again, and every situation that you're in, you have to 'come out'--until I reached a point where I didn't care anymore. I didn't have to feel like I was coming out. I stopped changing pronouns."

Xavier Mascareñas

"Coming out is not something that just happens once," Julian Spalding says. "It happens over and over and over again, and every situation that you're in, you have to 'come out'--until I reached a point where I didn't care anymore. I didn't have to feel like I was coming out. I stopped changing pronouns."

Xavier Mascareñas

Who And What Am I Really In Love With? For One Unconventional Household, The Answer Lies Within

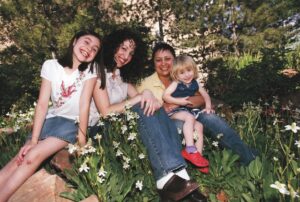

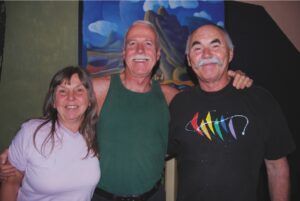

Lydia, Anthony and Tom.

Jessica Cassyle Carr

Lydia, Anthony and Tom.

Jessica Cassyle Carr

Pre-dinner milling around.

Jessica Cassyle Carr

Pre-dinner milling around.

Jessica Cassyle Carr