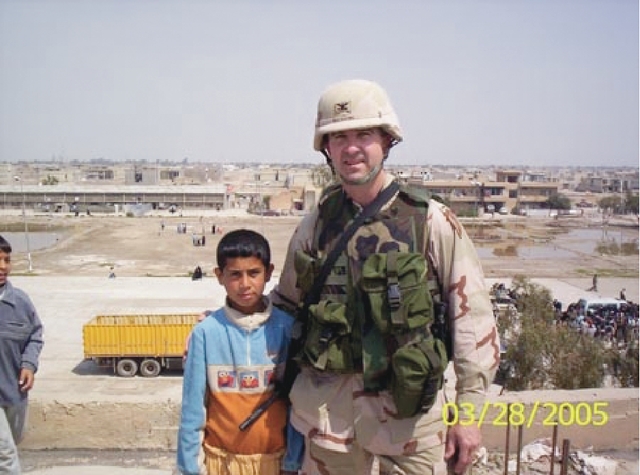

My commander’s suicide note to General Fil and General Petraeus as obtained through the Freedom of Information Act following my tour of duty in Iraq: I cannot support a msn [mission] that leads to corruption, human rights abuses and liars. I am sullied—no more. I didn’t volunteer to support corrupt, money grubbing contractors, nor work for commanders only interested in themselves. I came to serve honorably and feel dishonored. I trust no Iraqi. I cannot live this way. All my love to my family, my wife and my precious children. I love you and trust you only. Death before being dishonored any more. Trust is essential. I don’t know who trust anymore. [sic] Why serve when you cannot accomplish the mission, when you no longer believe in the cause, when your every effort and breath to succeed meets with lies, lack of support, and selfishness? No more. Reevaluate yourselves, cdrs [commanders]. You are not what you think you are and I know it.COL Ted WesthusingLife needs trust. Trust is no more for me here in Iraq. Dear Colonel Westhusing,I know you probably won’t get this, seeing as how you’ve been dead for some time, but I wanted to let you know how sorry I am about what happened to you over there in Iraq–especially given the way things are going over there now, what with all the progress that’s been made and whatnot (fatalities down, new insurgents killed daily, electricity back on, etc.). I’ve learned something about you since getting back, that you were too good for the lousy lot of scoundrels that you got thrown in there with. Too good for that lousy war. And I’m including myself alongside the other piglets that turned a blind eye to the bilking of American taxpayer money that took place there every dirty second of every dirty minute of every dirty day of that dirty war, right up until June 5, 2005, when you said No mas and put a bullet in your head. False invoices, false statistics, false training programs, false reports. Calculated, manufactured lies to generate war profit! And not just for a few hundred dollars or few thousand dollars, but to the tune of millions upon millions! Dollars that Americans labored to earn, then entrusted to their government to spend wisely. Hah! You must have been truly sickened, then outraged, at the shameless dishonesty among the “money grubbing” contractors you were forced to work with. Flannery O’Connor’s bible salesman all grown up, am I right? Slowly killing you with their sleaze and immorality. What the hell were these bastards doing in a war zone, anyway, filling their dirty sacks with money, on hallowed ground where better men than they–fighting men, Rangers (like you and me!)–were dutifully serving? The thought of those bastards in their pressed jeans flying to Dubai to deposit their bundles of shrink-wrapped cash and go jet skiing makes me sick to my stomach. Really sick.This is the thing, though. Sometimes I wonder if I should have known things were coming to a head with you. I mean, maybe I should have known. Certainly if we had spent more time together I might have. The way you were dipping Copenhagen toward the end like a fiend, practically living on it, turning pale as a ghost with it. But what was I supposed to do? Read your mind? Analyze the spit in your Styrofoam cups for signs of outrage and disgust? Really, Colonel, how the hell was I supposed to know you were on the verge of putting a bullet in your head? In any event, I was sort of preoccupied myself, wouldn’t you say? Up there in Taji with the coconuts? One setback after another! If your job was to report our progress (failure) to Fil and Petraeus, then it was my job to manage that progress (failure), right? I mean, we had our hands full with managing progress (failure) up in Taji, didn’t we? It was all-consuming. You got the reports from these same fingers! Things couldn’t go sideways fast enough. Iraqi commanders getting abducted, vehicles that couldn’t be repaired for lack of parts and tools, units disappearing into the desert like they never existed, leaving us holding the bag. And you know the bag I mean. That empty bag you carried around with you like you were going to fill it with something (meaning), like you needed to fill it with something (significance), but everything you reached for, everything you went to put in your bag just retreated ever so slightly, just beyond the reach of your fingertips. It was driving you crazy. Sure it was. Like the voice of your wife from a million miles away. That world—this world—like a fantastic dream, going on a million miles away. Where things were good and decent and made sense. Like the perfect woman, according to that old goat Salman Rushdie: “so perfectly attentive, so undemanding, so endlessly available.” But all you had in Iraq was a world of shit! Nothing perfect about that! And there was no escaping it. A world of conmen and shysters. Pinocchio’s underworld. You don’t even have to admit it and I know it. We weren’t doing anything together in that desert if we weren’t carrying empty bags around trying to fill them and going crazy with it, am I right? I was there, going crazy with you. But I was too caught up trying to survive my war to notice how your war was going. And your war had no business ending the way it did, Colonel, and I’m real damned sorry about what you came up against over there in the Iraq—the louts and scoundrels; the treachery; the black, soulless pit of cash-money-greed that finally did you in.Here’s the hard part I hate admitting. I really hate to admit this, Colonel, believe me. But when I got the news, you know, about your death, I wasn’t even that moved. What a terrible thing to admit, I know, believe me. But I remember it quite clearly: the nonchalance with which I took it, like your suicide wasn’t a big thing but just another crap detail in the crap world that was our existence in Iraq. I can tell you exactly what I was doing at the time—giving a lecture to some Iraqi recruits on why they could no longer wash their dirty feet in the sinks of the portable bathroom trailers in our tent city up there in Taji, which you probably remember as a giant cesspool. Remember how dirty and stinky that place was? It was like a Haitian refugee camp on crack. Am I right or what? Those were some insane living conditions. Anyway, what I remember is me and the Iraqi recruits, we’re all sweltering in one of those damn tents that we probably paid some contractor a million bucks for, and they’re looking bored and surly, tapping their flip-flops like they’ve got someplace else to be, and I’m lecturing them pretty good, and F. walks in and gestures to me from the door like he’s got something important to tell me. So I go outside where the sun was shining like a sonofabitch—you know how hot it was there in the summers, just suffocating us with it—and he puts his hand on my shoulder and leaves it there and says, “Colonel Westhusing just shot himself in the head.” Just like that. Now, Colonel, I’ll be honest, I barely blinked. It was like, “So our commander’s dead … anything else? Because I’m busy giving a lecture in there, trying to keep the sinks from all getting destroyed , and there’s a war going on, to top it all off. Plus we got mice.” Really, it was completely inhuman the way I barely registered your death. But the war was like this living, breathing thing of such immense importance. Remember? It was like nothing else mattered, not even your own limbs. Not even your own sanity. It was like you just got the hell blown out of you by a roadside bomb, wake up in Ramstein with one leg missing, and all you can think is, “But the other leg is fine, right? I mean, the other leg is good to go, right? Because I can still fight with one leg …” Crazy. It was like the war had totally eclipsed our every thought and feeling, our every idea, our every waking and sleeping moment. Because it was so huge, so monumental. History itself in the making! I mean, when had you ever felt this way before? You hadn’t. It was too big. And the horrible part of it was that you were surrounded by shysters and conmen in the biggest thing that you had ever been a part of. And they were all lying to you, lying to your face, making a mockery of your West Point ethos of Duty, Honor, Country. And those shysters and conmen, those war profiteers, they were laughing at your simpleminded devotion all the way to the bank. And when you went topside with reports of corruption and fabrication of training achievements, no one wanted to hear it. No one wanted to hear about the rampant failure of our mission in Iraq, about all the wasted billions of mismanaged money. Don’t rock the apple cart, Colonel. This is Iraq, Land of Bedevilment. Rivers flow upstream, then downstream, then stand still, brown and murky, then disgorge plump, bloated bodies to sharp-beaked egrets for a good, sturdy pecking. It’s the heat. Addles the brain. Don’t think on anything too much. Just do your time and get out of the sandbox. You know what they say about grieving, right? That sometimes things are so crazy you can’t even take a couple seconds to grieve? Well, that’s the way it was for me, but you can probably tell that already, I’m sure, the way I’ve been going on with it. But I’m grieving now, Colonel. I’m grieving because you bought it over there, and it seems like I’m the only one remembering it. And I’m not even that good at it. For instance, I’ve been killing it up on the slopes all winter on my snowboard, absolutely killing it! And I don’t think about it at all when I’m killing it, when I’m shredding all that white powder, so clean and bright and pure. I shred it right and proper, sir. You should see me up there, the liberties I take with it! Bottom line is I don’t think you were crazy for doing what you did, even though the Army psychologist who interviewed us came out with a report saying you were—crazy to think those contractors would be anything but profit-driven pondscum. But the psychologist didn’t know you, did she? She didn’t know the kind of man you were, a man who wouldn’t stand hand-in-hand with it any longer. Not with any of it. Not one second longer with those fat cats bagging their treasure trove, padding their pockets, then padding the lining of their pockets, then padding their inseam until they were shrouded in their filthy lucre, their bloody lucre.But there’s something else. Beneath it all I wonder if you couldn’t have been a little less upstanding and principled. I mean, couldn’t you have been a little more like me? A little less good cadet and a little more bad cadet? West Point dropout instead of West Point standout? I went there too, you know. Didn’t finish, though. Not principled enough, resisted indoctrination like a coked-up lab rat. But I knew how to have a little fun in Iraq, didn’t I? I mean, there wasn’t much fun to be had, I agree. But sometimes you just had to do something . Remember those Rambo Runs that F. and I would take to come visit you in the Green Zone and pick up our mail? I know those shenanigans drove you crazy—two yahoos flaunting all security measures and driving down alone from Taji to Baghdad in an unmarked suburban with tinted windows, two rifles and a handful of magazines, rocking out to the Foo Fighters like we were going out for groceries in a bad neighborhood. I mean, that was just stone-cold insane now that I think about it. Talk about a couple hoopleheads! But the brilliant thing about it was no insurgents would ever have suspected that we could be so stupid ! But we were! That’s the delicious part! Risking a YouTube execution to bring back mail and a case of black market Foster’s to our little cesspool of a world. You want to talk about a beer run, Colonel . I don’t even think them good old boys from Prohibition times had to deal with the threat of roadside bombs and getting their throats carved by masked avengers. But, of course, you weren’t wise to our activities, were you? Certainly we knew better than to let you in on our indiscretions. You would have strung us up, you old ringknocker, you. All rules all the time, right? But sometimes I wonder if a couple cold ones wouldn’t have done you good, put things in perspective for you. Maybe you would have realized that there could be life after this stain, after this miscarriage of a fiasco. Maybe.I’m hurting that this war cost you your life. I really am. Which is why I’m writing to let you know how sorry I am over what happened to you over there. And to say I respect and stand with you, Colonel. Less principled and less upright; but as far as I can manage, from here among the living, among the glittering mountains that kiss it so cold and good, this Ranger stands with you against the darkness that clouds our way.

After 15 years in the Army, including a tour in Iraq from November 2004 to September 2005, Alex E. Limkin hung up his rifle to pursue a career as a lawyer. He remains indebted to the Army for bestowing upon him an inviolate belief in his ability to endure all manners of hardship, deprivation, pain and spiritual darkness. He retains the warrior ethos of his Ranger brethren.