The Fight

T.J. Trujillo (left) blocks a right hook from Jason Quintana (shirtless).

Eric Williams

T.J. Trujillo takes a high kick at Jason Quintana (shirtless).

Eric Williams

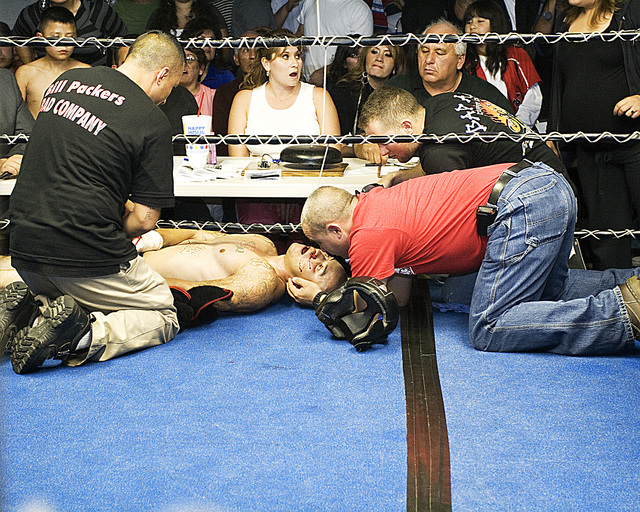

Jason Quintana lies semi-conscious, attended by trainer Fernando "Fernie" Calleros (left), after T.J. Trujillo knocked him out with a high kick and left hook to the head during the fourth round.

Eric Williams

Jason Quintana (left) gets T.J. Trujillo up against the ropes.

Eric Williams

Before a screaming sold-out crowd, Jason Quintana (shirtless in black-and-red trunks) attacks T.J. Trujillo (in red shorts) with a fury of punches.

Eric Williams