Road To Somewhere: Tijeras Canyon, The Sandia Mountains—And La Madera Road

Tijeras Canyon, The Sandia Mountains—And La Madera Road

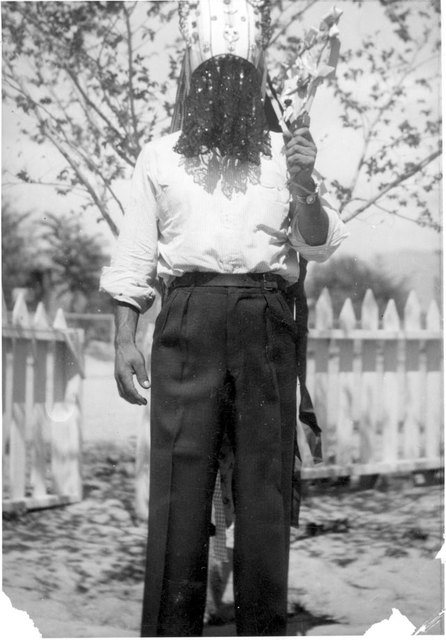

A Matachine dancer in San Antonio, NM, in the 1920s

Towns of the Sandia Mountains Project