A History Of Balloon Fiesta: How Media Marketing Transformed The Autumn Sky

How Media Marketing Transformed The Autumn Sky

Cutting Flying Service aircraft hangar circa 1960s

Cutter Aviation

William P. and Virginia Dillon Cutter pose with a Beachcraft Bonanza.

Cutter Aviation

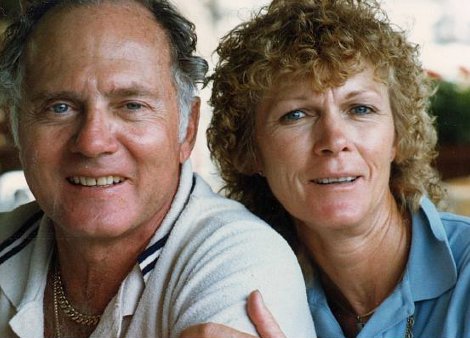

Ben and Pat Abruzzo were passionate about ballooning. The couple died in a plane crash near Albuquerque together in 1985.

National Balloon Museum

Maxie Anderson

National Balloon Museum

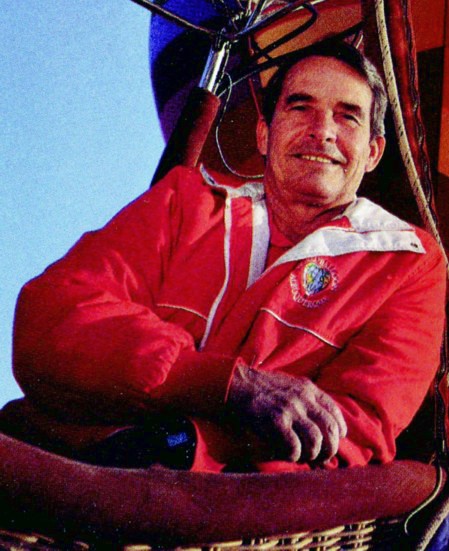

Sid Cutter in the technicolor ’80s

National Balloon Museum

Double Eagle II over Normandy

Bettman Archives

William Cutter chats with a mechanic out on the West Mesa

Cutter Aviation