Parched?

Albuquerque’s Drinking Water Project Goes Into Effect Next Year. Do You Know What’s In Your Glass?

Lisa Robert on her front porch in Tomé, N.M.

Christie Chisholm

The top part of an ad the City of Albuquerque ran in national magazines in the early ’80s to attract residents and bolster economic growth.

A map of how water from the San Juan River is diverted the the Rio Chama (making it San Juan-Chama water) and then to the Rio Grande, traveling nearly 200 miles before it reaches Albuquerque.

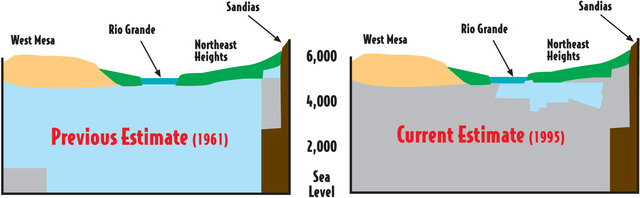

Conceptions of what people thought the Albuquerque aquifer looked like pre-1993 (left) and what it actually looks like.