The History

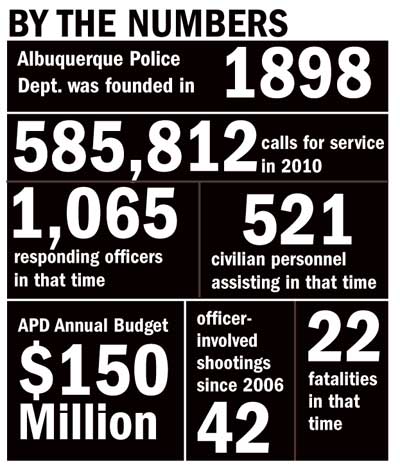

The predecessor to today’s police reviews is what’s come to be known as the Walker/Luna report. It was completed after a rash of deadly shootings in the ’90s. There were 30 officer-involved fatalities from 1989 to 1999, often involving emotional people holding harmless items. (For comparison, in the last five years, there have been 42 officer-involved shootings in Albuquerque, and 22 fatalities.)Two nationally known out-of-state police experts, Professors Sam Walker and Eileen Luna, concluded that Albuquerque’s citizen complaint system was ineffective. Settlements for lawsuits against police were inconsistent, they wrote, and the Public Safety Advisory Board was dysfunctional. The professors suggested a citizen oversight commission replace the weak advisory board.The Walker/Luna report included the American Civil Liberties Union’s 11 essential ingredients for successful police oversight and accountability. Among them: The commission should maintain independence, have investigative powers and reflect the diversity of the community. This report eventually brought about the Police Oversight Commission and the position of independent review officer (filled today by William Deaton). It also gave rise to APD’s increased use of less-than-lethal options, such as beanbag guns and Tasers, though officers weren’t required to carry Tasers until May 26, 2011.Dim Oversight

Peter Simonson, executive director of the ACLU of New Mexico, says the goals of the Walker/Luna report regarding oversight have not been met. “We have not had much to do with the Police Oversight Commission in the last few years,” Simonson says. “My observation is that it has not been very effective in addressing overreaching police abuse.” That’s because the commission’s studies and reviews are nonbinding, Simonson says, which means there are no rules requiring action based on the commission’s advice. The commission and the review officer also don’t have the power to impose sanctions or punishments. Sometimes the two produce contradictory opinions. Civil rights attorneys Frances Crockett Carpenter and Joe and Shannon Kennedy had a run-in with one such conflict. They filed a wrongful death lawsuit on behalf of Kenneth Ellis III, a 25-year-old Iraq War veteran who was shot and killed by APD in early 2010 [“An Army of One,” Jan. 13-19, 2011]. Review Officer Deaton ruled the shooting was not justifiable. The commission disagreed and tossed his opinion in the trash, sending its version to the mayor. Crockett Carpenter says the city must have a strong review process. “The citizen police oversight system should be civilian-ran, financially and otherwise independent from the city,” she says. “People need to know they have a truly impartial place to air complaints and begin the process of seeking resolution.” Faulty as it is, she says, at least there’s something in place. As things stands, the all-volunteer commission is selected by the mayor and approved by the Council [“Who Watches the Watchmen?” Sept. 16-22, 2010].The Watchers

The idea of a citizen review board has been tossed around in one form or another since 1978, when the City Council created a short-lived Police Advisory Board. That year, a federal grand jury investigated allegations of police brutality by APD. Over the next 20 years, APD tried various accountability methods, but nothing lasted. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that the commission was set up to address citizens’ complaints. Still, many of the public comments at meetings accuse the commission of siding with the police more often than not. Simonson said if the oversight commission were truly effective, it would not see such a high number of complaints. “At the end of the day, the courts are the best place to keep police in check.” In 2009, the commission received 209 complaints: 55 of those were sustained, the rest were ruled either not sustained, unfounded or exonerated. The first quarter of 2010 showed 129 complaints with 19 sustained. Commissioners have repeatedly stressed over the years that officers should routinely use their belt tapes to record their interactions with the public, and supervisors should impose stiffer penalties when they’re not used. By early 2010 the oversight commission said the department’s officers had responded to its requests for more belt-tape use, which helps commissioners make better decisions. The department is also making use of video-lapel cameras.The commission was evaluated by the Police Assessment Resource Center in 2002. Though the oversight process had potential to be effective, substantial reform and improvement were needed, according to the report. A similar study was done in 2006 by MGT of America that pinpointed the same problem areas. There should be more public outreach, and the department could better handle the aftermath of officer-involved shootings, MGT wrote. The city should reconsider the length of terms for Internal Affairs detectives, the researchers added, because people who are in that position too long may not be able to maintain impartiality. The report from this year’s updated MGT evaluation is expected in a few months.The Shootings

The late-June report done by the Police Executive Research Forum looks at contributing factors in the shootings in the last five years [“Police on Police,” June 30-July 6, 2011]. The report does not identify any one particular cause but notes that some officers are repeatedly involved in violent incidents. The study shows 22 percent of APD officers were involved in 60 percent of violent encounters with citizens. It also notes that an increase in violent crime was not responsible for the jump in the number of officer-involved shootings.The 2011 findings are similar to the 1997 Walker/Luna report that encouraged the use of Tasers, beanbags or other less-than-lethal measures, better training, and better recruiting of officers with good problem solving and people skills. Though the Walker/Luna report and the Police Executive Research Forum report occurred 14 years apart, both address how the department handles police shootings. They say the police department needs better reporting and data collection on the use of force in violent incidents. There should also be quicker and more comprehensive reviews of APD shootings, they conclude, as well as better training for officers. Both reports say the police department, the oversight commission and the review officer should accept and investigate all citizen complaints—even those that come in anonymously.Skeleton in the Closet

Complaints have triggered past investigations into APD. In 2005, the city weathered a state probe into lost, stolen and missing evidence such as guns, drugs, jewelry and money. The evidence room fiasco brought down then-Chief Gilbert Gallegos, and several other high-ranking supervisors were punished. This prompted then-Mayor Martin Chavez to hire someone who could put the department back together. Police Chief Ray Schultz answered Chavez’ call and returned to town from a stint as a deputy chief in Scottsdale to try to straighten things up. By June 2010, two disorganized, overstuffed evidence warehouses were cleaned out and reduced to one well-organized facility. Six years after the evidence room scandal, Chief Schultz talks about the progress. The physical facilities housing evidence have been revamped, he says, and so has the way evidence is gathered, handled, logged and stored. More checks and balances are in place, as well, he adds.“Our evidence room has been described in our accreditation process as a model for others,” Schultz says. Fixing this mess was a top priority, he adds, which included upping the number of trained evidence-handling personnel. Computer bar-coding stations were installed at each substation to log in evidence, which means it’s returned quicker after cases are closed. Schultz says with all evidence housed in one location, about $100,000 a year is saved in costs.What’s Next?

Mayor Richard Berry and Schultz issued a statement saying the city would work with the federal Justice Department in its investigation into APD. APD’s plan for the next few years outlines pages of goals and strategies for the police department. They include training, policy reviews and reducing the fear of crime within the community. Schultz says the strategic plan creates a framework for the department to address issues and measure successes. The plan also gives an APD contact person for each initiative. Schultz asks that all police officers and interested city residents read the plan and offer feedback.Download APD’s 2011-2015 strategic plan atcabq.gov/police/reports

Make Your Public Commentsfor the three-year review by Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies, Inc.Monday, Aug. 22, 5 p.m. City Council Chambersbasement of City Hall, 1 Civic PlazaIf you can’t attend, call 768-2465 on Tuesday, Aug. 23, between 2 and 4 p.m.