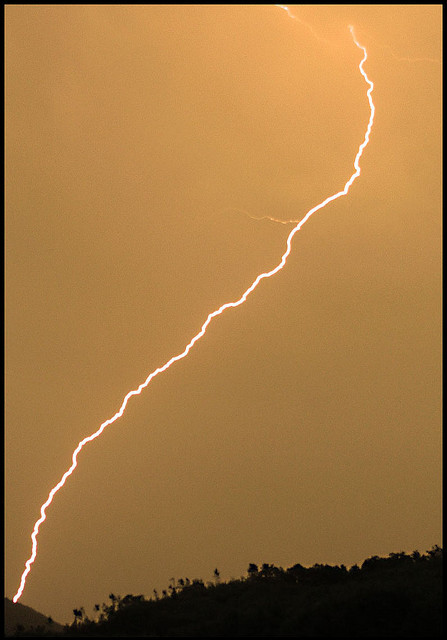

An average of 18 veterans commit suicide each day. The source for this statistic is not some obscure group with an anti-war agenda but an organization that probably knows something about the rate at which veterans are killing themselves—the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.I mentioned this statistic in passing to an acquaintance, a retired schoolteacher, and his response was to let out a low whistle and say, “Soon there won’t be any veterans left.” And maybe this is the point. Every veteran who kills himself is one less potential terrorist, one less potential Benjamin Colton Barnes, one less distraught soul. And the more veterans kill themselves, the less the country has to deal with listening to us.Not long after I wrote about the death of Barnes, I had a chance to connect with a small group of veterans and experience the Sawatch Mountains of Colorado. I was a little nervous about the trip because I didn’t know who would be there, and meeting new people isn’t easy for me. But the Outward Bound trip coordinator explained that my dog Abigail could come along, so I went. Outward Bound began in Wales in 1941 and trained young sailors to help them withstand the rigors of sea duty. A few years ago, the organization began providing wilderness courses to veterans at no charge. The opportunity for veterans to connect with other veterans and experience the backcountry away from society has proven to be invaluable, particularly for those dealing with post-traumatic stress.Founder Kurt Hahn viewed society at large as suffering from a decline in fitness, initiative, imagination, skill and self-discipline. His curriculum was modeled to address these failings. Today, Outward Bound has added an international peacebuilding branch, a reflection of Hahn’s dedication to cooperation and compassion among all people. There were six other veterans on the course, all male. I was the only one in my 30s. Everyone else was in their 20s. It was not long before we lapsed into the juvenile pranking so prevalent within all the branches of the military, but more so in the combat branches—especially among the infantry, which constituted most of our group. But beneath the banter and joking, some of us were wondering how we had managed not to kill ourselves. And not abstractly wondering but wondering in the particular. It turned out most of us had had problems staying alive and maintaining a sense of direction and purpose. Some, like Jerry*, a 25-year old Marine who did tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, entered phases of hard-core professional drinking. Mark, 29, went through a long period—as in months—of not leaving his room: “Just smoked pot and watched ‘South Park.’ ” He would later blurt out, angrily, after a course instructor gently intimated we should be proud of our service, that he was in fact not proud. “I was over there committing war crimes … responsible for a whole generation of Iraqi men missing from the landscape,” he said.But perhaps the most important thing I heard was a story told by Brad, 27, a veteran of the Korengal Valley fighting documented in the film Restrepo . It was the evening of the fourth day, and we were camped at 11,000 feet in the Collegiate Peaks Wilderness. The temperature was not much above zero degrees, and we were sitting in a snow kitchen fashioned with our avalanche shovels. In the freezing darkness, among bulky coats, occasional foot stomping and muted conversations, we resembled the inmates of a Siberian gulag. But we felt at home.Brad was talking to Jerry, and I was halfway listening in, holding onto a cup of cocoa, feeling Abigail shivering slightly beneath my hand. The bench of snow was cold but bearable. “Let me tell you this story,” Brad said. “There’s this Zen master out walking with some students in this massive storm.” It’s completely dark, he continues, and they’re on a narrow trail. If they stop, they die of exposure. If they keep going, they risk wandering off the trail to their deaths.“So what they do is, they wait for a flash of lightning, get their bearings in that brief moment and continue on as long as they can,” he says. Then they stop again and wait for another flash. Haltingly, they make it safely to the monastery. A student says to the Zen master, “I’m glad we made it. I was worried I would die before reaching enlightenment.” The Zen master shakes his head and says, “Enlightenment is not the sun that shines all day but the lightning that gives only quick glimpses, allowing us to move from one troubled place to another.”“That’s what you have to do,” says Brad. “Keep moving. Keep fighting.”In the darkness I don’t have to disguise my emotion.That was the same heart that brought us into the service in the first place, the belief that there was something bigger than ourselves, which we were willing to die for, and which we all discovered in the end was not some notion of our country or democracy or the capitalist system. It was our flesh and blood brothers, the ones we ended up getting tossed into the mix with, the ones we confided in, the ones that may or may not have come back with us. Brad reminded me of something I have been wanting to say for a long time:Stop wasting us. *The names of the veterans have been changed.

Alex Escué Limkin served in the U.S. Army for 15 years, including a tour in Iraq from 2004 to 2005. He documents his experience as an Iraq veteran at warriorswithwesthusing.org.

Outward Bound is accepting course applications for veterans at

outwardbound.org.

The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.