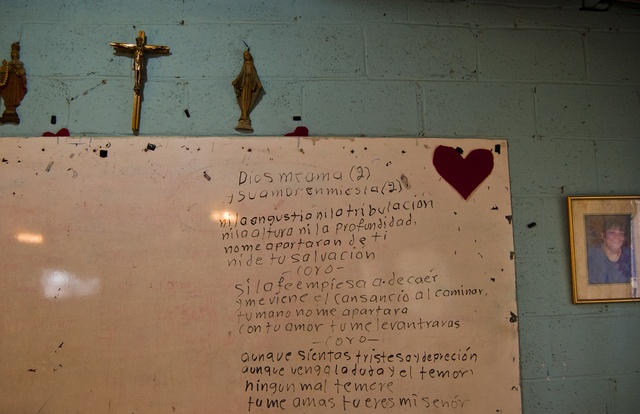

Though the U.S.-Mexico border is fortified to stem the flow of immigrants and drugs, news images from Ciudad Juárez still pour through.There are the bodies shrouded in white sheets sprawled on the street. Soldiers deployed by President Felipe Calderón prowling with automatic weapons. Hotels converted into safe houses for off-duty cops who are hiding from gangs that vowed to hunt them down.It’s a place to be avoided at all costs, says the U.S. State Department, which has issued stern warnings against travel to the city.“A former Marine told me at one of our fundraisers that he wouldn’t cross the border into Juárez for anything,” says Sister Rene Weeks. “He asked me how often I have to travel to the women’s center.” She’s a willowy woman with graying hair, round glasses and a ready grin. “When I told him I go over every day, his jaw dropped.”Weeks sees Juárez as being full of regular people—more than a million of them. If she can be a resource for some, the risk of crossing the border is worth it. But she’s used to going against the grain. “I was a typical teen rebel,” says Weeks, reflecting on her decision at 18 to become a nun and enter a Dominican convent in Kansas. “I’d had enough of my mother telling me what to do.”It was the ’60s, and some women were rebelling against conventional expectations. But most were still expected to marry young and were unlikely to work outside of the home, she says. “As strange as this may sound now, the convent was actually a way for a woman to have a less restricted form of life.” Sisters became administrators of hospitals or principals of large schools—leadership roles that weren’t otherwise available to women.It happened gradually. Over time, she “fell in love with the Dominican spirit,” she says, which isn’t so much about preaching truth as seeking it. “We try to help people find their own value and worth, as they are valued by God. We were really encouraged to follow what we heard as the voice of God within us and within the community.”Decades later, that voice led her to Centro Santa Catalina, a community center and women’s work cooperative on a desolate edge of Juárez. A Deadly City The working poor amassed along the fringes of Juárez are young families relocated from all over Mexico, enticed by the promise of jobs. They’re struggling under a double burden of worldwide economic recession and local bloodshed in a place hardened by years of disappearances and violence.On the north side of the fence, Weeks rises early to pack her lunch and a baggie of contraband to smuggle past the border guards—food for the limping puppy that sometimes appears on the street and follows her to work. She drives her SUV through El Paso’s clean, orderly downtown, through the line of cars at the border checkpoints. The guards wave her through. On the other side, looking like El Paso’s sickly conjoined twin, Juárez is waking up. Weeks is at ease navigating, pointing out historic landmarks and the lack of street signs. Her first days alone were more frightening.“I was following directions slavishly because I was scared of getting into an area where I didn’t know where I was, or how to get back out of it,” she says. As the newness wore off, she relaxed. “It’s a matter of staying alert. I don’t think to myself, Oh my God, I’m going to Juárez. Will I come back alive? Basically, I just go.”She says it wasn’t long ago that revelers and tourists streamed over the border to experience a piece of Mexico and spend money in the city’s seedy but vibrant downtown. Today that Juárez seems a lifetime away. Faded storefronts are gutted, their windows gaping or boarded over. There’s not a single gringo in sight. As night falls, even the locals evaporate off the street.During the sister’s commute, however, the roads bustle with activity. Couples stroll hand in hand. Men in work clothes bicycle past burned-out buildings and murals. This scene eased her initial concerns about working in Juárez, despite arriving in the midst of the deadly narco turf war. “People are going along with their everyday lives. You see them in the street, and they’re laughing. You have to go on with life. You just have to.” Island of Security Centro Santa Catalina is a humble cluster of walled-in buildings at the edge of Pánfilo Natera, a colonia perched on top of the former city dump. Residents are the working poor who initially squatted on the land, improvising rows of cinderblock houses or shacks from crates and cardboard. A jagged mountain looms to the west. During windstorms, dust rises from the old mounds of trash. People leave dead dogs around the neighborhood or burn discarded heaps of tires. Inside the walls of the center, the mood is bright. Every day at 9 a.m. the night watchman unlocks the front gates, and women and children stream in. Staff from the community tutor primary school-aged children, most of whom can’t afford the tuition of regular school. Some women oversee a low-cost kindergarten. Becoming the director of Centro Santa Catalina was only a slim possibility at first. The original executive director had decided to step aside after 18 years, but the job description looked too administrative for Weeks’ liking. “Then I went to the center and spent two days there,” she says. “The women won my heart.”Members of the center’s sewing cooperative arrive to set up their workstations, where they make scarves, bags and tablecloths for Sister Maureen Gallagher and other volunteers to sell in the U.S. Each earns a monthly wage for her work—a good one, by Juárez standards. They can receive counseling—psychological or spiritual—from Weeks or visiting volunteers. Several raise vegetables in a neat row of covered beds on the property. Eight women lead a spirituality and leadership program, reaching out to mothers of the school kids so that skills and values taught in their classes can be reinforced at home.“A lot of the women will say to me that before they started coming to the center they were pretty much closed up in their homes,” says Weeks. “They didn’t go out much or really see other people.” Often, it was because their husbands objected. “It’s a macho society in many ways,” she says. “Eventually they were really able to change that attitude. I see the center helping the women becoming more confident in themselves.” Some have even gotten scholarships through the center.The camaraderie of the place helps foster normalcy and hope for women burdened by worries about money, domestic violence and safety. The small-business sector has all but collapsed in Juárez, leaving thousands without work. Killings spill into the center’s hillside neighborhood. Weeks says the well-being of these women is linked to that of the area because they are breadwinners—and also the primary caretakers of many children.Retired El Paso schoolteacher and Centro Catalina board member Rachel Pineda says the center struggles with financial difficulties. Through it, she’s observed Weeks’ determination to instill self-sufficiency in the women who depend on it.“She’s gone without getting paid some months because she wanted to pay the tutors and women first,” says Pineda. “She’s a very skilled organizer and tries to teach them more of the responsibility that’s involved in running the center.” Once, the phone line was out for two weeks and the women expected Weeks to take care of it. “She insisted that they make the call and fix it themselves. That’s how you help make it sustainable, because now they know how to do it.”Weeks acknowledges that dwindling numbers of young women choose the spiritual life of service that she did. She worries about the long-term prospects of the center. Yet as she interacts with the women on the sidelines of the leadership class—with hugs and words of encouragement, bouncing their babies on her lap—it’s obvious that her focus is embodying the values she carried to Juárez. Today’s workshop theme: nonviolent communication.“The congregation I belong to is called the Dominican Sisters of Peace,” she says. “We try to be peace. When some of the other sisters heard I was coming here, they said, That’s wonderful. That’s where we need to be. What better place to do this work?”