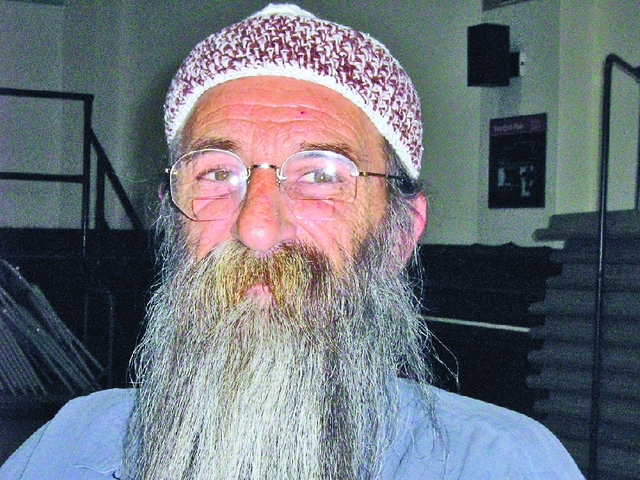

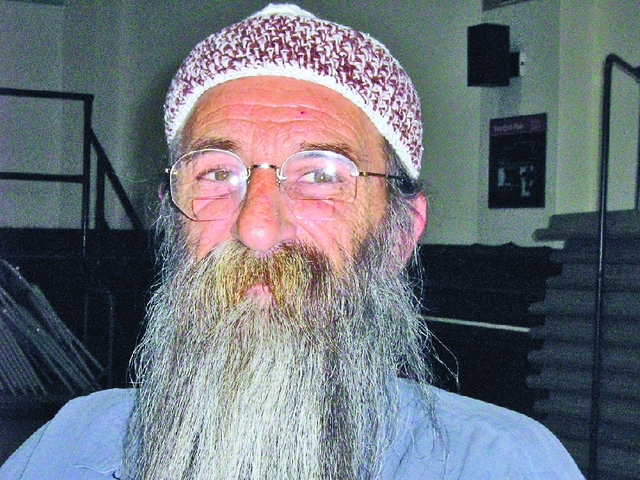

“Single beak parrot,” says the smallest person in the room. His eyes sparkle behind thick glasses and his silver beard is almost long enough to tuck in his belt. “Brush the clouds.” “Skim the waves.” “Stork cooling its wings.”Sixteen combat veterans follow the little man’s fluid moves. The class is being held in the recreation hall on the Veteran’s Administration Albuquerque campus. It’s a bright, airy pueblo deco-style room. Large pine beams cross the ceiling. Colorful kachinas line the columns. But the posters of jet fighters don’t let you forget where you really are. “He’s the Dalai Lama,” the woman next to me says as she flows from “left leg rooster” to “right leg rooster.” I try to keep up and stagger off balance. She gives me a kind, peaceful smile. I later learn she was a combat nurse in Vietnam and saw things none of us ever want to see.This Dalai Lama wears Dickies workpants and speaks with an accent straight off the streets of Queens, N.Y. He was an Army helicopter medic in Vietnam. That’s where he got his Post Traumatic Syndrome Disorder. Everyone here brought back PTSD from their war. “Are your palms hot?” he asks during a break. Yes, I answer. They’re burning. He’s pleased.His name is Tony Vignali. This is his 109 th consecutive tai chi class for fellow veterans still fighting the psychological and spiritual effects of combat they experienced decades before. He’s a volunteer. Since 2005 he’s been leaving at 3:30 a.m. from La Joya, many miles south of Albuquerque, to lead this class. He does it every Tuesday and Thursday, regardless of weather or how he feels. Now he drives to Belen and takes the Rail Runner from there. As spring settles in, he’s adding a Friday class outdoors.“I’ll be driving up in the most awful weather, thinking no one will be here. But these people always show up. It blows my mind,” he tells me over a green salad at the Nob Hill Flying Star. Vignali was drafted into the Army at age 18. He credits parochial school nuns for inspiring him to be a medic. “I was good at grabbing people and putting them back together. But that’s also how I got my own PTSD.”He won’t share much about what he went through in Vietnam, except to say, “I had an altercation with the ground.” I didn’t expect him to give me more. I’m not a veteran. Some things veterans share only with other veterans.He was first introduced to tai chi in Taiwan, in 1967. He later studied it intensively when back injuries put him into a wheelchair. Tai chi helped save him. The Iraq war motivated him to use his knowledge to help fellow vets.“I don’t know how the Vietnam War affected my dad, who fought in World War II. But this war really bothers me. So instead of just bitching, I decided to get busy.“I can’t really stop the war. I know that. But I can help deal with the aftermath. I can help [returning veterans] calm down so they don’t waste 15 years like I did trying to get my head screwed back on straight.”He teaches a form of tai chi that emphasizes breathing. “Combat veterans have issues with breathing. They hold their breath a lot because of the stress of war. We’re taught to hold our breath when we shoot. But breathing is the key to relaxing. They need to relax so they can deal with their stuff. And breathing is pill-free.”And it works. “They’d come in at first with arms locked across their chests, head back, lots of apprehension. You know the look. Now guys stand taller, breathe easier. I don’t see balled fists anymore.”Veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan have been checking out the class. “They come in looking bewildered and wary. They’re going through the same things we went through. Being with other vets takes that away. They’ve got a place to come that is safe, and to focus on something together outside of combat.”“Vets helping vets,” he continues, “is pretty new. It is growing and the VA is welcoming it. They really need the help. They’re stretched thin. And guys like me have matured enough to where we’re able to help.”I bring up the stories about the mistreatment of veterans at Walter Reed in Washington, D.C. Vignali only gushes praise for the Albuquerque VA facility and staff. “It’s a community, not an impersonal hospital. The staff are very dedicated. They’re truly healers. They’re making a difference. And where else can you get live mariachi music first thing in the morning? You gotta be really fucked up if mariachis don’t perk you up.”I kept wondering what was so different about this diminutive, bearded Italian guy from Queens squinting at me through his thick glasses. For one thing, he won’t say anything worse about another human being except that they’re “pesky.” He also exudes something setting him apart from the people around us in the restaurant and on the street when we walk back to the car. The word eventually came to me: grace . Vignali shines with grace. It’s in his face and the few glimpses he allows into his soul.“I used to be really angry that I got drafted and went to Vietnam,” he said after he opened up. “But, oddly, for the last 10 years, I’ve been glad I lived through hell. Now, as an older man with that experience behind me, I’m able to do things I wouldn’t have had the moxy to do. Like being gentle. I know it sounds strange to say you need moxy to be gentle. But I’m gentle because I know how easily we can get hurt. And I saved a guy’s life last week without even thinking. He was choking to death so I just put my fingers down his throat and made him breathe. Being glad I went to war in Vietnam, I guess, is like someone who’s thankful for the experience of cancer. It’s hard to understand unless you’ve been through it.”

The opinions expressed are solely those of the author. E-mail jims@alibi.com.