Good Medicine

An Interview With The Man Who Met The Medicine Men

Nolan Rudi

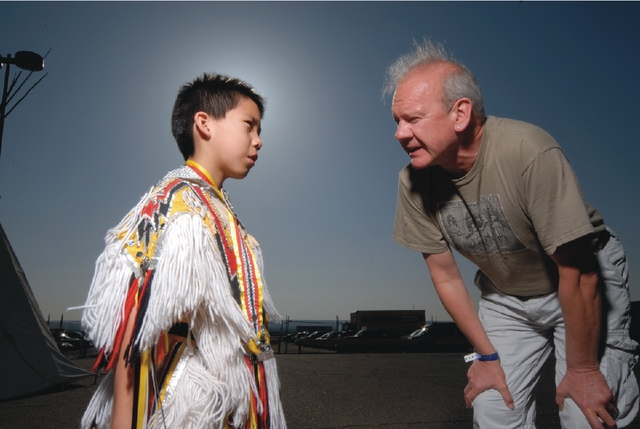

Charles Langley (right) talks to a boy named Eddie at the Gathering of Nations.

Nolan Rudi

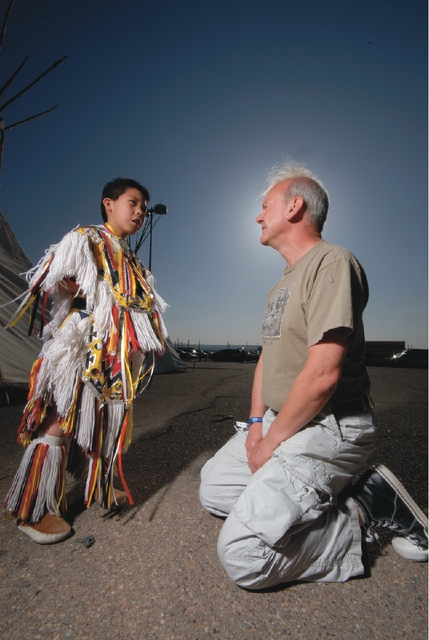

“It was like the floor had been peeled back, and suddenly I as looking down into a completely different universe.” —Charles Langley

Nolan Rudi

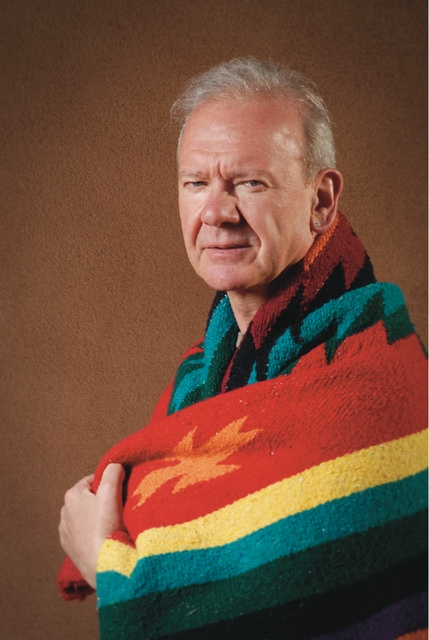

“Razzle Dazzle” at the Gathering of Nations

Nolan Rudi