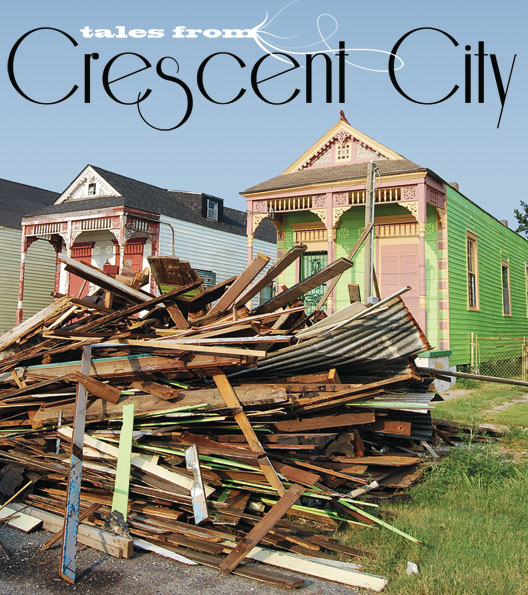

I’m clopping along Royal Street. It’s nearing midnight on Saturday and I’m heading from a show on Decatur, weaving through the French Quarter on my way to the Marigny. In the interest of the procurement of cigarettes, I bolt into the first bar I meet. The Golden Lantern is draped in a humble and inviting facade, and inside a U-shaped bar fills the main room. Low lights are interrupted by the glow of a cigarette machine and a television playing music videos. I stuff a five-dollar bill into the machine, then go over to the bar. I don’t intend to stay. While I wait for the bartender, I glance around: One man wears a mustache and has a John Waters-meets-Droopy look about him. Another seems like a slightly updated Faulknerian gentleman. Across the bar from them, three rotund fellows sit smoking. As the bartender approaches, I notice he’s wearing a cowboy’s outfit, complete with hat, bolo tie, huge belt buckle and a sleeveless shirt unbuttoned to mid-torso. Yes! I’ve fallen into a gay bar, I think with satisfaction. I explain to him that I just need matches and won’t be having a drink. As he lights my cigarette, he and a tattooed man two stools away encourage me to sit a spell. Fifteen minutes later, drink in hand, I’ve learned that the tattooed man, Doug, is a computer programmer who splits his time between San Francisco’s Castro and New Orleans’ Marigny. Together we muse about New Orleans’ gloriously surreal qualities. Right before a conversation about the necessity of home urinals takes off among the cowboy bartender and the all-male remainder of patrons, I have to leave. They may have thought I didn’t want to discuss urinals, which couldn’t be further from the truth. The next evening I visit the Golden Lantern again and the same thing happens. Different bartender, different barflies, different conversations, and I make three new friends. This is just the way it works in New Orleans.***Founded in 1718 by the French, La Nouvelle-Orléans changed hands between France, Spain, France again and the United States over the course of its early history. By the 1800s the area of land nestled between Lake Pontchartrain and the Mississippi River Delta grew into a wealthy port city, the result of river commerce and the slave trade. It was also a meeting point of cultures. The influx of French-speaking Creoles from the Caribbean kept the town Francophone, while the mixture of Caribbean, African, Mediterranean and European influences established an unequivocally distinct culture.On Aug. 29, 2005, New Orleans was devastated when a giant, swirling mass of wind and water named Katrina came from the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall. An evacuation was mandated before the monstrosity arrived. With its assault, federally maintained levees and floodgates failed, and 80 percent of the city flooded. People were trapped atop roofs and freeways with no help in sight. More than 1,600 people died in New Orleans. Martial law was declared, and evacuees couldn’t return home for weeks. When they did, they faced not only damaged property, but a national disaster area barely limping along on dysfunctional infrastructure and disorganized leaders. ***At my dad’s shotgun house in the Bywater, a plastic bag stuffed with chocolate chip cookies sits on the kitchen counter. His neighbors, Glenn Howard and Joe Skylas, have dropped off another installment of perfectly executed baked goods, and as I masticate one of them, I call the couple to arrange a chat. It’s not long before I’m sitting at their lovely dining room table, in their beautifully decorated home with two handsome cats occasionally rubbing against my leg. The couple, who moved here from Chicago in 2004, were the next year spared much of the hurricane damage that many others sustained. They weren’t flooded, or looted, or taken out by the tornadoes that whipped through the area. Only wind damage and, like everyone else, an unrefrigerated refrigerator full of rotting food were their immediate burdens. Since then they saw the cost of living rise dramatically, while quality of life decreased. They say their homeowner’s insurance went from $1,500 per year, pre-Katrina, to $5,000 per year after the storm. They also mention serious problems with the police force, pointing out that the National Guard still provides supplemental policing. Glenn says that without them he thinks it would be chaos. Joe tells me that a month ago, somebody broke into the still boarded-up Fifth District Police Station. It was wide open for roughly a week before anyone noticed. Despite what they call a lack of visionary leadership in terms of recovering the city on any governmental level, Glenn and Joe extol New Orleans. "It’s not as unsafe as maybe it’s portrayed in the media. If you come here as a visitor, I don’t think you’re gonna see crime unless you go looking for it," Joe says with Glenn in agreement. "People shouldn’t stay away. It’s a very beautiful city."***Earlier this year, my little sister and I arrived in town fresh off of a cross-country drive from San Francisco. That night we struck out in search of a bar. We passed a dozen before a magnetic force drew us into Molly’s at the Market. There, we met Robert Clark, who unexpectedly came to be our favorite bartender in New Orleans.Hailing from the same North Louisiana parish as my sister and I, Robert, a New Orleans resident since 2002, returned to the city shortly after the storm. During a recent visit to Molly’s, he tells us that at the time it was like a weird cowboy town. Roving bands of 19-year-old National Guardsmen armed with M16s roamed the city, drinking in bars, stopping at block parties to have beers. With the city’s infrastructure still in disrepair, like many displaced New Orleans residents, Robert took a “hurrication” that fall, setting out on a crazy road trip that took him to Mexico, California, Canada, back to Mexico, then back to New Orleans. He says it was the right time to commit to the city. "It’s magical. It’s like living in a movie. I’ve just become so desensitized in a certain way," he says. "You never know what you’re going to see. You turn the corner, there’s a guy you know getting a blow job from a clown in the dive bar down the street. Stories like that come up every day, and you don’t blink an eye, you don’t doubt it."***On Saturday nights for the past 14 years, rare groove and deep funk has emanated from radios tuned to WWOZ 90.7 FM, a station "dedicated to bringing New Orleans music to the universe." The person behind the show, called “Soul Power,” is the Soul Sister, a well-known local DJ, crate digger and woman informed with expansive knowledge of New Orleans music. At the mellow Hookah Cafe on Frenchman Street, over crawfish bisque and some really girly drinks, I ask Soul Sister if she thinks New Orleans is back. She says almost definitely. "That’s why I’m back, and that’s why so many other people are back. That’s why we are sitting here in a fabulous restaurant having a conversation, you know? If people didn’t believe in it, it wouldn’t be as awesome as it is now."One thing making the city so good, she says, is that Katrina made people more aware of what they love about New Orleans. The effect has been that people are less likely to take things for granted or fret about small stuff. On top of that, there are burgeoning underground arts and music cultures. She—and many others—point out that when the city was evacuated, residents brought New Orleans culture to other cities, and brought the essence of other cities home. This exchange has worked to create new artistic energy in the city, adding to the creativity and unique quality of life that’s already existed in New Orleans for generations. ***Three years after the storm, throw a maraschino cherry in New Orleans and you’ll hit someone with a Katrina story. Back at the Golden Lantern, on my last night in town, I am engaged in marathon conversation with the bartender, a New Orleans-loving Dutchman and the other guy next to me. We discuss hurricanes, rising sea levels and various forms of deluge. Diagrams are drawn, drinks are drunk, the city is worshipped. As I walk the four blocks home alone at 3 a.m. that Sunday night—feeling completely safe—I’m imbued with a new intimacy with the city. As fraught with new and pre-existing problems and blight as New Orleans may be, it remains the infinitely interesting cultural mecca and rare illumination it’s been for centuries. Oh man, you should see it for yourself.

Feature

Author’s Note: I wrote this story because people kept asking me about New Orleans. I’m not from the city, and haven’t lived there. I was born and raised in Louisiana, and have been visiting New Orleans and family there all of my life. Earlier this year, both my father and sister made permanent residences in New Orleans. But while I’m somewhat familiar with the city and absolutely love it, I don’t pretend to know it like its denizens.

Go to alibi.com to see more photographs from New Orleans.