River Water In Your Glass

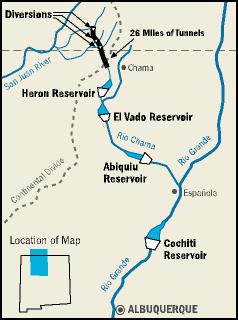

Albuquerque's Water Supply Is About To Change

The city’s new water treatment plant under construction

Courtesy of the Albuquerque-Bernalillo Water Utility Authority