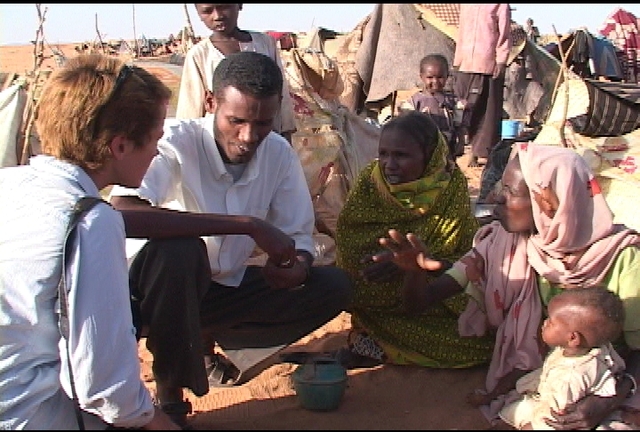

For six years, Amy Costello covered conflict zones in Africa, genocide in Darfur, child labor in Ivory Coast, AIDS orphans in South Africa. She worked as a correspondent for the BBC’s "The World," Public Radio International and WGBH Boston. Ask Costello for a memory, and the story she tells is a curveball.She was reporting on a drought, interviewing a farmer while he stood among bone-dry crops. He was desperate, she says, and had plenty of children to feed. She thanked him and left to interview other villagers. Late in the day, Costello and her crew were leaving town in a vehicle and passed by the farmer’s house again. "I see him come running down this very long dirt driveway," she says. "He’s running at this fast pace, and I say, What’s going on here?" They pull over, and the farmer approaches her window. "He presents me with this gourd, a beautiful orange squash. It was preserved and hollowed-out and dried. He hands it to me with just a big smile on his face, and the translator said something like, This is a gift for you. Of course, I had nothing for him." Costello carried the gourd on her lap all the way back to her home base in South Africa, and later, to the United States. Costello moved back to the states and took a safer job as an adjunct professor at Columbia University a couple years ago. "I’m a mother now with a 3-year-old girl," she explains. "I’m not willing to put myself directly in harm’s way."The gourd, she says, represents her humbling experience in Africa. "He was willing to part with something that was beautiful, that he had probably made with his own hands, and to me, which represented a much better time in his life when the earth was bearing fruit." Costello’s report "Sudan: The Quick and the Terrible," broadcast on PBS "Frontline," was nominated for an Emmy Award in 2006. She will give the keynote address at the Amy Biehl Youth Spirit Awards ceremony on Tuesday, Dec. 2. She spoke with the Alibi about her reporting experiences and what it means to choose to confront suffering. Do you think the United States has a blind spot when it comes to Africa? There could always be more attention in news media paid to stories from Africa. Unfortunately, we’re living in a time now where there are so many urgent stories, like Iraq or Afghanistan or Pakistan. China, Russia, you name it. News media organizations are shrinking rapidly, and they don’t have the resources to devote to coverage of Africa.Increasingly, what we’re seeing are freelancers like myself. That’s how I got started in Africa, just going and doing those stories. And [freelancers are] doing amazing work at great personal risk. You’ve done reporting on a lot of gruesome things. Have you been forced to confront those things personally? How do you deal with that? It took a huge personal toll on me, doing the work that I did. I largely traveled alone. I had no colleagues with me. I had no one to talk about what I’d seen at the end of the day. I was married but my husband was thousands of miles away from me. After a particularly gruesome trip to Congo, I went and saw a couple of therapists, because I felt like I wasn’t dealing with it when I got home. They said I had some elements of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and that’s something that a lot of journalists confront who go to conflict zones. It’s an issue that a lot of us are largely silent about, because we’re supposed to be these tough reporters and nothing really affects us and that kind of thing. Are there restrictions on the press in some of the places you visited, and did they apply to you? No. For the most part I would report my stories after I got out of the country. I would take all my material and my interviews and then go back to South Africa where I was living and then file my stories from there. Not really for any security reasons. It was because that was kind of the way that I worked in terms of deadlines and stuff. I didn’t go around a lot on the streets with my microphone out. I would dress very casually. I probably looked more like a backpacker than a journalist. I didn’t make myself known all the time, that "Hey I’m a foreign journalist." How do you think your experience differed from the local journalists who were also covering things in those areas? One of the most basic things is I could get interviews. I felt that I could report stories as I saw them without fear that I could be imprisoned or, God forbid, tortured. Or that my paper would be bombed, which is a very real reality for people in many countries. What goes on in a lot of places is considered self-censorship. It’s not so much the government coming in and saying, "You can’t write this" or "You can’t say this." But just the threat that if you say the wrong thing you’re going to be put in prison causes a lot of self-censorship. They never even get to the point where they’ve written a controversial article, because they’re too frightened to. And those that do take the risk, bad things happen to them. This isn’t everywhere. And I think there’s lots of growing freedom of the press in many nations, but there’s still certainly a great number who don’t have true freedom of the press and that’s very unfortunate. What’s it like to head into these places as someone from a completely different cultural background? For the most part, it was a wonderful experience. A lot of people were interested in the fact that I was a woman traveling alone in Africa. I found being a woman an advantage. I think I was never seen really as a threat. People were often sometimes so surprised to see me show up in some of these places, they kind of wanted to protect me more than anything. In the worst circumstances, no matter how much tension there was in a place, or if there was conflict going on, or if they were recovering from conflict or if there was a food shortage, by and large, despite all those things, people were incredibly welcoming and friendly to me. That’s the kind of thing we miss in the coverage of Africa. We see it as conflict zones where there’s tension and killing and that kind of thing, but my experience is that there’s this whole other side to Africa, and that was incredibly welcoming. I felt very safe and very well taken care of really wherever I went with few exceptions. Why are you coming to Albuquerque to speak at the Amy Biehl Youth Spirit Awards? I met Amy Biehl’s parents a couple of times and her mother a few times in South Africa. One of the first stories I ever reported was about the hearing of Amy Biehl’s murderers. I was in the hearing when they were testifying in front of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission about how they had killed Amy Biehl. Her parents were there in the same room. It’s very odd to me, in a way, that one of my first stories … I feel like I’ve come full circle. I plan to talk about how the Biehl parents’ lesson of forgiveness toward their daughter’s killers informed my reporting and the way that I’ve chosen to live my life, which is to get up close to people that are suffering, which is what they were willing to do. They were willing to literally embrace and figuratively embrace the killers of their daughter. In some ways, I’ve tried to emulate that in terms of getting up close to really difficult situations. I’m going to encourage the young people who have already done so much with their lives in terms of volunteering in their own communities, to continue to get up close to people, to get up close to suffering. It’s a difficult thing to do, but I think it’s really easy in our society to isolate ourselves from suffering and from people who are difficult to be around. I hope to challenge them to continue to get up close to people.

Amy Costello will speak at the Amy Biehl Youth Spirit Awards on Tuesday, Dec. 2, at 5:30 p.m. at the KiMo Theatre (423 Central NW). Tickets are $30 and available through Ticketmaster. For more, go to amycostello.com or amybiehl.org.