The Weatherman And Me

Mark Rudd: Political Organizer, Ex-Federal Fugitive, My Pseudo Stepdad

Mark does some rabble rousing inside an occupied University of Columbia building in May of 1968. Behind him is a photo of Che Guevara.

Mark tells the crowd to chill out as police look on. The rally was held to protest the construction of a gym that would displace low-income residents in Manhattan.

Mark during his days at Columbia

In one of the few pictures taken while the couple was underground, Mark and my mom marvel over her pregnant belly during the summer of 1974. Paul was born before they came above ground.

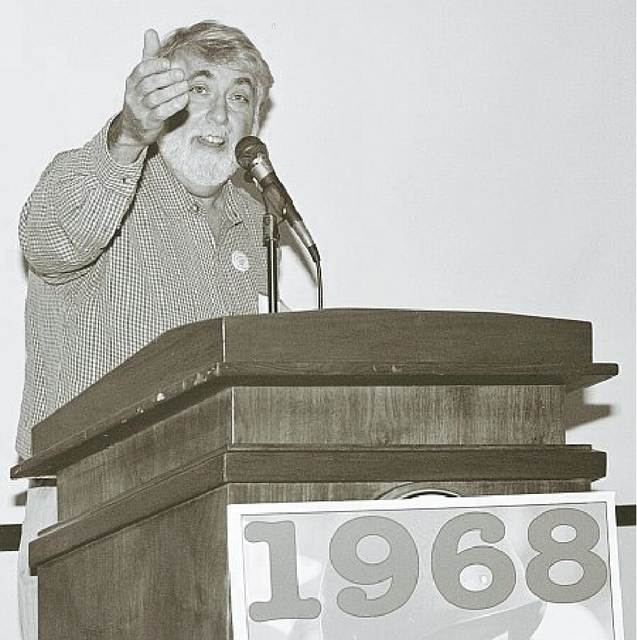

Mark speaking to a history graduate students’ conference at Drew University in 2006.