Diminishing Legal Turf

What We’re Working With

Taking It To The Streets

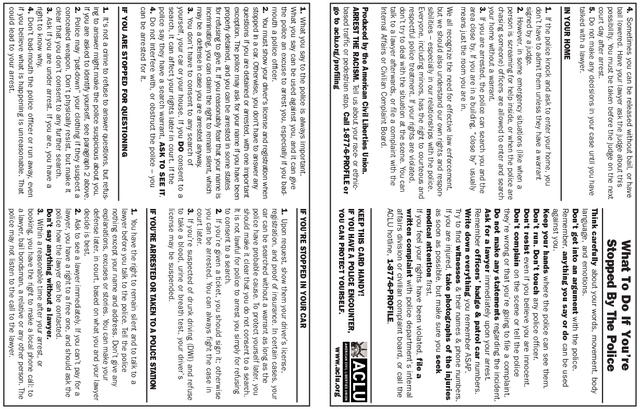

How Not To Get Shot

A Drive-Thru Primer

Warrants, Search And Seizure

Independence Day

Feature

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992