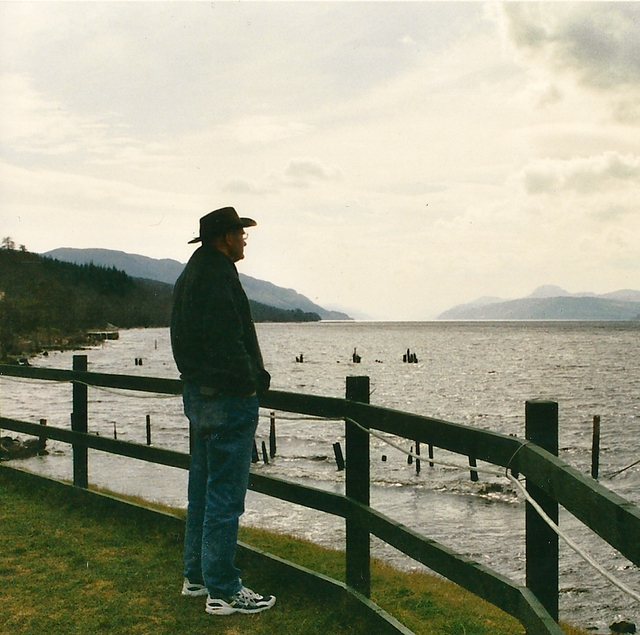

Steve Feltham’s eyes and smile grow wide when the subject of the Loch Ness monsters comes up. “I think they’re out there, certainly,” he says, though he adds with a hint of sadness that it may not be true for much longer. He estimates there are probably a half-dozen creatures left in the lake (down from dozens in earlier eras) and will be fewer each passing year: “Sightings have declined. They’re gradually dropping off of old age, I think.”I found Feltham more or less by accident. I was at Scotland’s famous loch for about a week in 2006 following a speaking engagement in London. There I discussed my original research into “America’s Loch Ness Monster,” the creature supposedly inhabiting Vermont’s Lake Champlain. I had spent much of the day near Inverness, conducting a series of experiments to judge the size and distance of unknown objects in lake waters. But by mid-afternoon, the weather had grown too Scottish, and I had to pack it up. Instead of experiments, I walked along a chilly beach near the town of Dores, where, to my surprise, I found about 20 Loch Ness monsters. They were mostly red, green, purple and blue. Some were perched on rocks, others on little clear acrylic ice cubes, all on a wooden shelf supported by a waist-high tree stump. They were only a few inches high, and had big, cute eyes. Above them was a multicolored, hand-drawn sign that read, “Nessie Models For Sale.” Just behind that lay a converted minibus with faux wood paneling and a giant logo that read, “Nessie-Sery Independent Research.” It’s part tourist shack, part library, part monster research facility and all home to Feltham, the world’s only full-time Loch Ness monster researcher. Feltham, with his easy grin, a shock of gray and white hair, and clipped British accent, is a fixture at Ness. He’s lived on its shores since 1991, when he abruptly moved from England. The vehicle, which is not much bigger than some walk-in closets, has everything he needs: a sparse bed, a desk, a tiny sink and a cooking burner. The walls are plastered with posters, photographs, maps and shelves with Loch Ness-related books and papers. (I was pleased to see some of my own articles and research on his shelf.)Being both in the very shallow pool of serious lake monster researchers, we talked shop for an hour, swapping stories, research findings and theories about our elusive prey. He asked me about some of my lake monster investigations (a dozen or so of which appear in my 2007 book Lake Monster Mysteries: Investigating the World’s Most Elusive Creatures ), and he gave me a tour of his place. I perched on a tiny stool, and Feltham told me his story. He spoke of a fairly ordinary childhood and rattled off a list of his previous occupations: “I was a potter for a while. Then I installed alarm systems. You know, peoples’ houses, commercial, all that lot. And, I’m an artist, of course,” he quickly added, gesturing to the Nessie figurines. He sculpts them in his spare time (which he has a lot of) to earn a living, selling them for £10 each (about $15).Growing up, he’d always been fascinated by Scotland’s Nessie but never seriously pursued it. When he installed residential burglar and fire alarms in London, he said he’d usually make small talk with the owners, who were often elderly. As old folks are often wont to do, the pensioners shared stories of their lives. Feltham noticed a common theme: Many expressed regret at not having followed the dreams of their youth. One retiree had spent years working in a pastry shop and always wanted to open his own bakery but never did. Another woman once had dreams of moving to America and pursuing a career in dance or theater; instead, she spent 30 years in a comfortable but unfulfilling office job. Feltham took that as a sign that he should seize his dream of searching for the Loch Ness monster and dedicate himself to it full-time. He quit his job and left his friends, family and life to drive to Loch Ness to live alone in a van and spend all day, every day, looking for the beast (and greeting the occasional tourist).I knew better than most people what a bold move that was. A monster in Loch Ness, or any other lake, is a possibility, but a remote one given that there’s no hard evidence they exist. No such creatures have ever been captured. If they exist (and there would have to be dozens of them in the lake to sustain a breeding population), they have miraculously managed to avoid leaving any teeth, bones or carcasses. Loch Ness has been searched for more than 70 years, using everything from miniature submarines to divers to cameras strapped on dolphins. In fact, just three years earlier, a team of researchers sponsored by the BBC undertook the largest and most comprehensive search of Loch Ness ever conducted. They scoured the lake using 600 separate sonar beams and satellite navigation. One of the lead searchers, Ian Florence, was quoted in a BBC news release: “We went from shoreline to shoreline, top to bottom on this one, we have covered everything in this loch, and we saw no signs of any large animal living in the loch.” No monsters, no nothing. I asked Feltham what he thought about that. He leaned back in his chair and crossed his arms. “It was flawed,” he sniffed. “Yes, it made the papers, but they didn’t scan [the loch] all at once, so to me the results are suspect. They searched it over three days in three parts, so the animals might have moved around between the searches.”I understood his point, though it seemed unlikely to me that such a thorough search had somehow missed a half-dozen or more large creatures. I didn’t challenge him on it. Though I was used to being the skeptic when it came to eyewitness reports, Feltham shared my doubts about many sightings. He explained that many “eyewitness” sightings of Scotland’s famous lake monster can be traced back directly to Hollywood movies about the creature. He had no doubt that eyewitnesses sometimes describe seeing things they only really saw in fiction: “You remember the movie here on the loch that came out? The one with Ted Danson? Well, there’s a scene at Urquhart Castle that shows two Nessies there with long, thin necks.” That scene, Feltham told me, changed real-life eyewitness descriptions of things people saw on the loch: All of a sudden people started reporting seeing monsters with necks exactly as depicted in the film. “Nobody reported seeing 20-foot long necks until after that film came out,” he said. Unless the Nessie monsters had somehow seen the film and changed their appearance to fit what people were expecting them to look like, this was a clear example of how pop culture influenced the public’s sightings. He said a few years earlier he had been contacted by a woman offering a video of what she thought was the neck of the Loch Ness monster, low in the water. “She’d come out to the loch on holiday and had a video camera with her. She was out by the castle”—the ruins of Urquhart Castle, the most famous and most photographed spot on the lake—“on a tour, I think it was, and she’d panned along the shore and countryside. She didn’t think a thing of it at the time.” It wasn’t until she and her husband returned home that they watched the video of their vacation and noticed a long, dark, indistinct form seeming to come vertically out of the water. They were sure she had accidentally filmed the Loch Ness monster’s neck; what else could it be? “It was a boat mast,” Feltham said with a weary smile. “Clear as day, a boat mast. You don’t see the rest of the boat because she was taping the hills instead of the water, but there it was.” At Loch Ness—as at many reputedly monster-haunted lakes around the world—the bulk of lake monster sightings are made by tourists. If the creatures live in the lakes, one would think the people who spend the most time on the lakes would be more likely to see them than someone who’s only at the lake for a few days. Over and over I have interviewed fishermen and boat captains who have crisscrossed lakes daily (sometimes several times daily) for years and decades and never seen anything unusual. Feltham’s story provided part of the explanation: People who are around the lake often recognize normal features of the lake that weekend tourists might mistake for a monster head or neck (unusual wave patterns, masts, floating logs, swimming deer and so on). One of the most popular theories about what the Loch Ness monster might be is a dinosaur-like plesiosaur. There are myriad problems with this theory, including that plesiosaurs died out millions of years ago and that Scotland’s lochs are only about 10,000 years old. Feltham rejects that suggestion, offering instead his best guess: Nessie are probably fish, most likely catfish. I asked how he would feel if he was proven correct—if, after all the monstrous speculation and blurry photos, the world-famous Loch Ness monster really did turn out to be an ordinary catfish (albeit a large one). How would he feel if, after spending 20 years of his life searching for the mysterious beast, the monster turned out to be something most people can find in their local supermarket? He thought for a few moments and answered in a soft voice. “I guess I’d be philosophical about it,” he said as his sweatered shoulders betrayed a slight shrug.I bought one of his Nessie sculptures, shook his hand and wished him luck. As I left Feltham’s van / home / research center on the windy shores of the small, cold lake in Scotland, I couldn’t help admiring his dedication. People should pursue their dreams and quests—but realize that they can come at a high cost. When we hear news stories about Bigfoot or Nessie or ghosts (whether we believe in them or not), it is easy to forget that some people—in some cases, many people—are completely convinced they exist. Some hardcore enthusiasts spend precious years of their lives (and tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars) searching in vain. The line between casual interest, serious hobby and outright obsession can be a fuzzy one. I realized that Feltham and I were in many ways more alike than different. There are millions of people around the world who are interested in unexplained mysteries, yet you can count the number of serious, scientific investigators on one hand. Not the weekend warriors who go on camping trips looking for monsters or to cemeteries at midnight looking for ghosts, but people who have spent years and decades writing, investigating and researching the topics. For better or worse (I’m not sure which), Feltham and I were part of an exclusive club. Of course I didn’t quit my job, leave my friends and family, and go live alone in a minibus on a clammy Scottish lakeshore for my research. I liked to think that made me more grounded than he was, but maybe we aren’t so different. Part of me admired his certainty and wished I had the courage of his convictions. If I were as convinced as he that some strange creatures existed out in the loch—and that I’d discover their nature if I moved there and devoted my life to searching for them—would I do it? Maybe his obsession will pay off; maybe one day I’ll pick up a copy of the New York Times or the Albuquerque Journal to see a front-page story with a big color photo of Feltham, beaming his triumphant smile next to a monstrous beast he’d captured or found in the loch. Maybe he will go down in history books as having solved the most famous lake riddle of all time. But maybe he won’t. Whether plesiosaur, monster or catfish, there’s a certain irony in that if the Nessie creatures truly are an endangered species, they might live and die without ever having been proven to exist. Stories and eyewitness reports of the Loch Ness monster will continue—with or without any actual creatures in the lake. Tourists will continue to mistake floating logs, boat masts, fish, wakes and other normal lake phenomena for potential monsters. The existence of lake monsters, like that of Bigfoot and ghosts, cannot be disproved. It only takes one live or dead monster to prove forever that they exist. And until that time, Steve Feltham will continue his search.

Benjamin Radford has investigated mysterious and unexplained phenomena for more than a decade. He is a columnist for LiveScience.com and Discovery News and managing editor of Skeptical Inquirer science magazine. His latest book is Scientific Paranormal Investigation: How to Solve Unexplained Mysteries , available at his website: RadfordBooks.com.