A Wise Acre

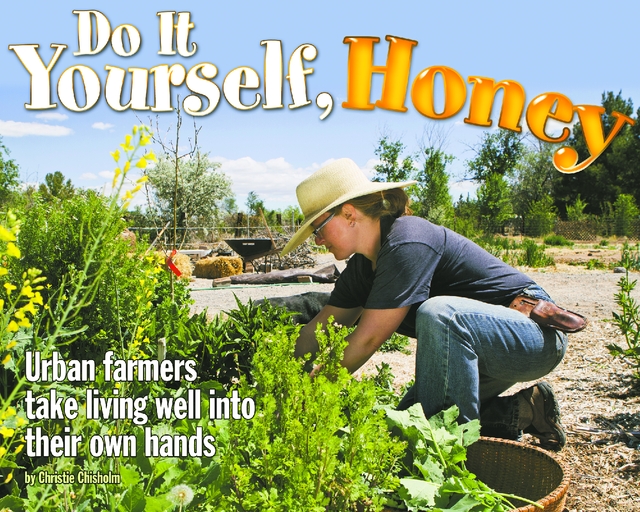

Jen Prosser began farming long before it was considered cool. She was going to school in New York City, studying to become a literature professor. But the more time she spent in classrooms, the more she found herself dreaming about being outside. When she was downsized from an administrative job and given a severance package, she used it to move upstate to the Catskills and start a farm with her partner, Tree McElhinney. The two raised goats and chickens and grew herbs and vegetables for about 10 years on their 21 acres. But it rains a lot in the Catskills, Prosser says—so much that it makes farming difficult. Eventually, Prosser and McElhinney began to crave the sun. After a countrywide search, they decided on Albuquerque. Packing up three goats, 10 chickens, two dogs and two cats for a cross-country move out West, they settled in the South Valley in 2007. Sunstone Farm and Learning Center sits on just one and a half acres, and Prosser and McElhinney can hear Coors Boulevard from their yard. But that one and a half acres is an urban oasis. The two harvest honey from three hives of bees. They raise chickens—including a particularly charismatic cuckoo maran hen named TicTac—for eggs and meat. Those three regal goats are milked, and their creamy bounty is made into cheese, yogurts and soaps. The couple also grow vegetables and fruits that account for about 60 percent of their diet. After living in San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York, Prosser is happy as a desert clam on her abundant plot.“In New York, people expected you to work 24 hours a day,” she says. “There can be a slower pace here if you allow yourself.” Prosser starts her workday at 5 or 6 a.m. every morning, but she stops when she chooses, which is usually in the mid-afternoon. It allows her the luxury to connect with the food she’s grown. She and McElhinney have what Prosser calls a “slow meal” every day, savoring the arugula and spinach grown in their backyard and sprinkling their salads with homemade cheese. Americans get most of their meat from cellophane-wrapped trays at the grocery store and their produce from parcels of land several countries away. In sharp contrast, the do-it-yourself movement champions all things homemade and local. But cultivating a relationship to the land and the food extends far beyond the pedigree of what’s on your dinner plate: It also requires a network of human relationships, as well as their shared bank of knowledge—techniques passed down from generation to generation that are strangely absent in modern society.Prosser found a greater appreciation for the “old-fashioned” way of doing things once she started growing her own food, she says. It was a gateway into traditional methods and crafts, like food fermentation, soda-making and composting. In a turn that seems fitting with her previous ambitions of being a professor, Prosser teaches classes on how to do all the things she’s learned: raising backyard chickens, creating an urban homestead, making goat milk soap, baking artisan bread. Many of her classes are devoted to herbalism, since Prosser is also an herbalist. In addition to teaching people about the practice, she does consultations.The participation at her classes is telling. “There seem to be two different kinds of people who attend: urban hippies and survivalists.” Those from the former category come because they want to learn how to be more sustainable, she says. The others come because they think “the rapture’s going to be here in five years.” They want the skills they’ll need to live through it. “It’s important to know how to talk to people who are different,” says Prosser. Finding common ground is just another facet of the urban farming movement. “I think all these things I do fall under the heading of ‘sustainable’,” she says. “But they all have an effect on the larger picture without politics or drama. It’s about creating abundance in your life.”Busy as Bees

While Foster found beekeeping out of pure interest and Prosser became a farmer out of a desire to get her hands into the earth, Maggie Shepard became a fluent member of the DIY movement for an entirely different reason: money. Shepard is the founder of the newly formed The Old School, a collection of teachers who host classes on how to do a variety of traditional crafts and skills. “My family and I don’t have a lot of money,” Shepard says. “Whenever I wanted to learn these skills myself, classes were too expensive.” Even if Shepard could afford a class, she had to find a babysitter for her two kids; it just never worked out. “I thought, There’s probably more people like me who can’t afford classes.” Shepard sent an email to everyone she knew in late February, explaining that she wanted to start a class series and was looking for teachers. In just two months, she’s already amassed 20 instructors offering 22 classes. The scope of the classes is wide-ranging: The Old School teaches about quilting, solar cooking, homebrewing, gray-water recapture, fermenting kombucha, container gardening, canning and making homemade beauty products. And that’s just a sampling. Most classes cost less than $10 to attend, and free or low-cost child care is available at all of them. Adding to the feel-good meter, 10 percent of all proceeds from classes are donated to Water for People. “As an American, I value independence and perseverance,” Shepard says. “And independence for me means being able to take care of yourself in the most dire of situations.” In this country, a dire situation is being without money, she adds. She thinks the DIY movement has arisen, at least partially, for that reason. “We’ve become so reliant on corporations to get milk, clothing, etc.,” she says. “It’s an expression of our need for security combined with a need for independence.”Foster comes to it from a different angle. Beekeeping doesn’t save her money. She eats and brews up flowery mead concoctions from some of the honey she harvests. But she gives most of it away. What she likes about the practice is the awareness it gives her. She notices when the elm trees in her yard start to bloom, as it’s the first pollen her bees get in the spring. This year, she just discovered that one of the bushes in her front yard has tiny flowers because she saw bees hovering around it. Like Prosser, it gives her a connection to her environment and a hand in shaping it.What she likes most about beekeeping, though, is more existential. A colony of bees acts as a super organism, with thousands of individual members working toward the same goal, often simultaneously. Like ants and flocks of birds and schools of fish, bees have their individuality—some take on nurse roles while others are guards or foragers—but they’re tapped into a larger form of consciousness created by the whole. They act collectively. Foster sees human populations the same way. “How do you convince 30,000 bees to swarm?” she asks. “How do you decide to overturn the leadership in Egypt?”Grow Your Own

Sunstone Farm and Learning Center offers classes and fresh food in the South Valley

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com

Sunstone Farm and Learning Center offers classes and fresh food in the South Valley

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com