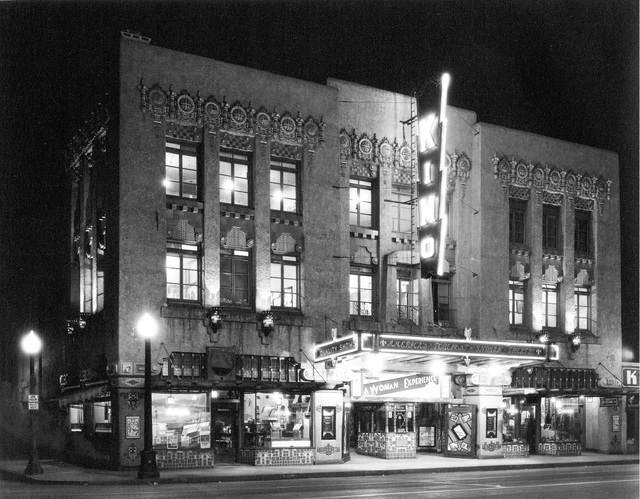

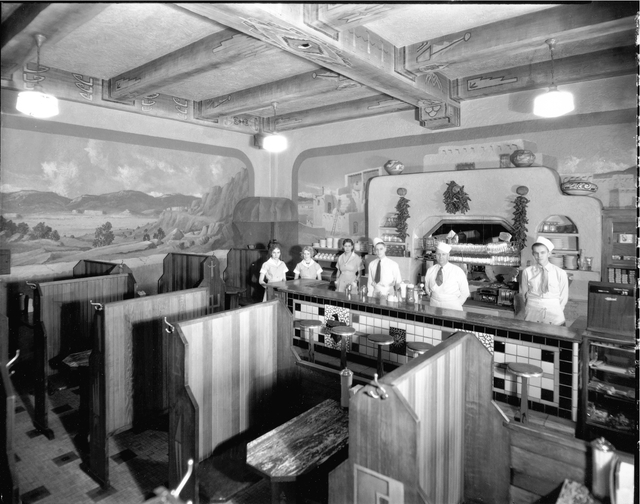

In the ’20s there was a fanciful architectural trend known as "atmospheric theater." Lushly decorated movie palaces were designed to transport audiences to other realms; to create the illusion of being outside on a starry night or in the midst of a different culture or locale. Downtown Albuquerque’s KiMo Theatre, built in 1927, is a surviving—and unusual—example of the style. Elaborate terra-cotta Hopi sun shields emblazoned with Pueblo and Navajo motifs drip from the exterior’s facade. Glowing cow skulls illuminate the lobby and theater. Carl von Hassler’s "The Seven Cities of Cibola" frescoes inhabit the walls of the mezzanine. Tile work, paint, molding and metal decorations echo the regional aesthetic in a montage that vividly adorns the building’s every nook. This week, with the installation of a replica of the KiMo’s original sign, the city pays homage to its most flamboyant architectural asset. Then Most atmospheric movie theaters of the ’20s were built in exuberant styles imported from other parts of the world, says Ed Boles, historic preservation planner for the City of Albuquerque. These included Mayan revival, Egyptian revival and Babylonian revival. “The KiMo was designed for this place," says Boles. "The architect went out onto Indian pueblos and reservations in the Southwest to get ideas for the design." It’s emblematic of the New Mexico’s frontier culture that those responsible for the KiMo’s creation were all from other places. Oreste Bachechi was an Italian immigrant and entrepreneur who moved to the U.S. in the 1880s. He first found success in Albuquerque running a tented saloon that catered to railroad workers. Bachechi commissioned the Los Angeles- and Kansas City-based Boller Brothers, well-respected national designers of atmospheric theaters, to build his "Theatre Albuquerque." The Boller Brothers were also responsible for Santa Fe’s Moorish-style Lensic, built in 1931. After traveling around New Mexico pueblos and reservations with German-born artist Carl von Hassler, Carl Boller laid out a design for what would be the KiMo. "It is a beautiful building. It captures a period of architecture that didn’t last that long," says Theresa Pasqual, director of Acoma Pueblo’s historic preservation office. "That was really coming at a time when travel was happening in and around Indian country. So there were people that were fascinated by the cultures that were here in New Mexico and chose to exemplify that through those particular architectural styles." The theater—built in a style that came to be known as "pueblo deco"—opened in 1927, its marquee reading for decades "America’s foremost Indian theater." It was named by Pablo Abeita, a former lieutenant governor of Isleta Pueblo. In the Tewa language, KiMo means "mountain lion" (for unclear reasons, "king of its kind" is the loose interpretation). The pronunciation of KiMo is nothing close to the way it’s commonly pronounced (it’s something closer to “emu”). "At the point of its construction, it was considered to be innovative and contemporary," says Ted Jojola, a Community and Regional Planning regents professor at UNM who grew up in Isleta Pueblo. Jojola says the theater might seem traditional in retrospect and that its builders were trying to develop a style with vernacular underpinnings. But it’s also congruent with the pueblo kitsch that was found all along Central Avenue at the time. "I just am incredibly happy that it has persisted in spite of everything else that has gone on with urban renewal in Downtown Albuquerque,” Jojola says. “It’s just one of those kind of quirky places that I think adds a real heart and character." In 1977 the City of Albuquerque acquired the KiMo from the Bachechi family. This was a few years after the Fred Harvey-Alvarado Hotel and Hotel Franciscan had been torn down, and one reason for the city’s purchase was to make sure the KiMo wasn’t lost. "Albuquerqueans understood that these buildings weren’t going to preserve themselves,” says Boles. “That at some point, people who cared about them had to get involved—and sometimes the City of Albuquerque had to get involved—to save them. In the case of the KiMo, they decided it was one they wanted to save." Now Boles says when the city bought the KiMo, along with being fire-damaged, it had been remodeled in ways that compromised its historic value inside and out. The city set in motion what has now been a 30-year process, rehabilitating it in stages as funding has allowed. With the return of the KiMo’s neon sign, which has been absent since somewhere between the late ’50s and early ’60s, the facade will look much as it did when it was new. "Putting that sign back on the front of the KiMo has been one of those final touches that just sort of says, Yeah, we really have brought the old guy back," says Larry Parker, manager of the KiMo. "It’s going to definitely redefine this corner of Central.” Funds for the 24-foot sign came from a general obligation bond for half a million dollars approved by Albuquerque voters in 2009. That money was also used for a new air conditioning system in the auditorium, equipment upgrades such as a sound board and HD projector, and to clean, repair and paint the exterior stucco, among other things. "We want folks to come back Downtown, and we want folks to come back to the KiMo," says Dana Feldman, deputy director of Albuquerque’s Cultural Services Department, which operates the theater. "I think the restoration and our new program changes are really in step with each other. … We have all kinds of things to offer at the KiMo now." The program changes Feldman speaks of involve opera, ballet, live music, radio broadcasts, Friday night features and a Charlie Chaplin festival starting this month and running through the summer. When Mayor Richard Berry was elected, he says he wondered why he hadn’t spent more time at the theater. To remedy attendance issues, he wanted to make the entertainment more sophisticated and the environment top-notch. He says the city needs to treat the KiMo as an enterprise in some ways so it can continue to maintain it and bring in interesting programming. "People are more than willing, for certain things, to help chip in,” Berry says. “In this case, it’s the ticket price." The 84-year-old building will always require general maintenance, but in terms of further enhancements, the city is considering placing a wine bar at the corner of Fifth Street and Central where the box office now resides. A café—the Keva Lo—was the original inhabitant of the space.Mayor Berry says the city has designs on restoring other historic buildings, too, but it’s not yet ready to reveal them. "We are looking around Albuquerque to make sure we’re honoring our past as we grow as a city,” he says. “Because one of the things that makes Albuquerque unique—we haven’t turned into what a lot of other cities have. We haven’t turned into a cookie-cutter city. We don’t want to do that." On Friday, the KiMo gets its sign back in a dedication that wraps up decades of work. The gala features a special showing of Fritz Lang’s 1927 silent science-fiction masterpiece, Metropolis . The screening includes 25 minutes of lost footage and a live score by Boston’s Alloy Orchestra. Adding to the event’s atmosphere, antique cars from the ’20s and ’30s will line Central. "There’s a lot of great history to be told,” says historic preservationist Theresa Pasqual, “especially in the Albuquerque area. All one has to do is look up and notice the architecture."

KiMo sign dedication / Metropolis screeningwith live score by Alloy OrchestraFriday, June 3, 7:30 p.m.KiMo Theatre423 Central NWTickets: $25, available via the KiMo Ticket Office, 768-3544, or at ticketmaster.comkimoabq.com