The death of Ray Bradbury at the age of 91 sent us on a time-tripping flashback to 1999 A.D. The famed author passed through Albuquerque then as keynote speaker at the 50th anniversary of Los Alamos National Labs. We were lucky enough to score an interview with the man. Then again, maybe luck had nothing to do with it. During a lengthy book signing he performed at Page One,Bradbury was approached by a teenage fan who wanted to ask the literary legend a few questions for his high school newspaper. Without hesitation, Bradbury handed over his home telephone number and said, “Call me.” Immeasurably gracious and inspiring to the end, Bradbury will never be missed–because he will always be with us through his timeless words.

Alibi Flashback

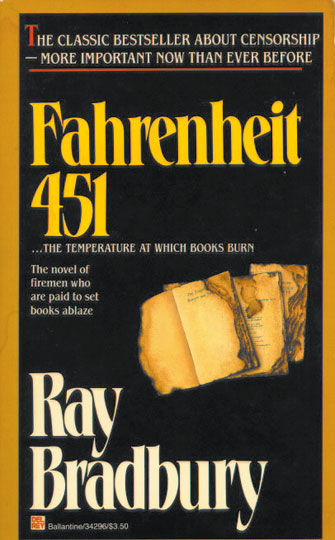

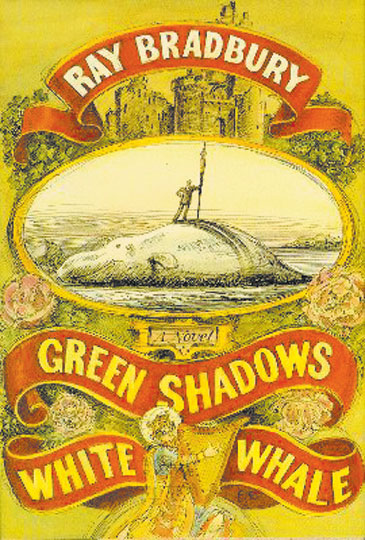

There are few people on planet Earth that did not grow up reading the words of Ray Bradbury. In a career that has spanned more than six decades, Bradbury has contributed some of the most memorable short stories and novels of all time. The briefest of lists would have to include The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man, Fahrenheit 451, I Sing the Body Electric, Something Wicked This Way Comes, The Halloween Tree. That brief list, of course, would leave off more than 70 novels, poems, plays, short story collections and essays dating as far back as the 1930s. He has been called “The Greatest Living Author.” But such a distinction gives a tad too much credit to all the dead ones. Bradbury is known to most as a science fiction/fantasy author, though the strength of his speculative prose lies not in technical understanding, but in human understanding. For all the fantastical elements in his work, every one of Bradbury’s stories transcends genre trappings. “R is for Rocket,” one of his most famous shorts, tells the tale of two young boys, best friends. One of them elects to go off to the Space Academy, the other chooses to stay home. Though the story is nominally set in the future, it is simply a story of friendship tested by circumstance. Bradbury was one of the first authors to show readers that, no matter where technology leads us, human beings will always be human beings.At age 79, Bradbury remains deeply enamored with the field of writing. In recent years, he has penned detective novels (A Graveyard for Lunatics), short story collections (Driving Blind), poems (Dogs Think Every Day is Christmas) and will soon release another collection of essays (Journey to Far Metaphor: Further Essays on Creativity, Writing, Literature and the Arts). In his 1994 essay collection Zen and the Art of Writing, Bradbury wrote that a writer should be “a thing of fevers and enthusiasms.” Bradbury’s enthusiasms remain unweathered by the years. As he closes in on his eighth decade, Bradbury remains a zealous eight-year-old enamored with carnivals, comic strips, space travel, Egyptian history, mythology, dinosaurs, Halloween and, of course, the future. Weekly Alibi recently had the supreme pleasure of chatting with Mr. Bradbury on all things feverish and enthusiastic. You’re coming to Albuquerque for the 50th Anniversary of Los Alamos National Laboratories and, apparently, you’ve been asked to speak about the next 50 years of Los Alamos. [Laughs] Great years ahead, yes. What can you tell us about the next 50 years? Well, we’re going to make it. In spite of everyone. The Y2K stuff and the fact that the whole damn country is stupid about when the millennium begins. It doesn’t begin next year at all. It’s a year later. … We’re going to spend a billion dollars—a billion dollars!—in celebrating an unholiday, January 1st, and of course it’s the wrong date. It seems that people look for those artificial markers of time. Well, they look at the year 2000 as nice round numbers. It looks as if it should be the new century. Of course it isn’t. But it’s natural. And there’s no use fighting it, so I’m just going to hide out that night. Probably a good move. Do you think the new millennium will actually bring about a change in people’s minds? Everyone seems so worked up about it. Well, it’s just a fake celebration. It doesn’t mean a thing. We all make our New Year’s resolutions don’t we? And then we break them the next day. The last century’s been a very fascinating century in which we’ve killed off death, haven’t we? We got the Salk vaccine. When I was born, people were dying all over the place of things like flu and pneumonia and scarlet fever and measles. Millions and millions of babies died in the 1920s. Starting in 1939, we invented the Salk vaccine and penicillin, and then we saved millions of lives every year since. So it’s been a good century. There’ve been a lot of wars, but every other century’s had a lot of wars too. We’re still on top of it, and soon after the new century—a year and a half from now—we’re going to go back to the moon. And then we’re going to head for Mars some time. And you’ll probably live to see it. Will you be discussing social as well as scientific changes as Los Alamos? Oh, everything. I’ll talk about space travel. I’ll talk about Darwin, Lemarck and Genesis. [Laughs] You name it. I never plan ahead, I just get up and explode. I’ve published 600 short stories now, so I’ve got lots to pick from, don’t I? With the way science is progressing, do you think writing science fiction is harder today than it was in the past? No. First of all, I don’t write science fiction. I’ve only done one science fiction book and that’s Fahrenheit 451, based on reality. Science fiction is a depiction of the real. Fantasy is a depiction of the unreal. So Martian Chronicles is not science fiction, it’s fantasy. It couldn’t happen, you see? That’s the reason it’s going to be around a long time—because it’s a Greek myth, and myths have staying power. Right. It doesn’t become outdated. Factual things don’t necessarily have staying power. So it’s easier today to write science fiction than when I was starting out, because when I was in high school, there were only four or five books a year published that you could call science fiction. And that was the time when Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World came out and some of H.G. Welles’ books. Today there are 300 new books a year. One a day in the science fiction field. Go into the nearest science fiction/fantasy bookstore, you’ll be smothered by the books! Young writers have a better chance today of making it and having an income than I did, because I started out in the pulp magazines making a half cent a word or a penny a word. So it’s a better time, because we’ve landed on the moon, we’ve photographed Mars, we have the space shuttle, we have TV, we have Internet and computers, all these crazy things that didn’t exist when I was a kid. All these things impact us and cause us to write science fiction. Do you think that science inspires science fiction, or that science fiction inspires science? We share. I’m accepted at CalTech. I go out and lecture there all the time, and they introduce me as “the man who put an atmosphere on Mars.” So they accept the fact that I’m not accurate. I was at a gathering of astronauts 33 years ago in Houston, and there were 60 astronauts there. They were getting ready for the Apollo missions. I was down there for Life magazine doing an article on space travel, and the publisher of Life told all the astronauts, “Today we have a guest, Ray Bradbury.” Half the astronauts jumped to their feet and turned and stared at me. They were all my children, weren’t they? So we influence each other. John Glenn read me when he was younger. All of them have read me. I’m very fortunate. Very fortunate. Being a creative writer trapped in the realm of journalism, I have to ponder the question—in a world based on facts, what is it that fiction does for human beings? What purpose does it serve to read things that aren’t real? It makes us dream and it makes us accomplish. Einstein had to dream first, didn’t he, before he wrote his theorem? Darwin the same way. The Wright brothers had dreams of flying. They lay in bed at night at the end of the 19th century and said, “I wonder how we can put wings on our bicycles?” And they finally did it. You’ve got to read myths—Greek myths, Roman myths, Egyptian—and you have to dream yourself into being. The purpose of fiction is not to nail you to the ground as facts do, but to take you to the edge of the cliff and kick you off so you build your wings on the way down. I have a great admiration for all the writers who worked during the heyday of the pulp fiction magazines. It seems like a time of great opportunity—the fact that there were that many magazines, that many people reading. What was it like working during those times? It was very difficult, because you couldn’t make an income on a half-cent a word. How do you live on that? I made a penny a word, so I was making around $20 a week. That was enough to keep me fed and to buy my clothes. But when I got married I was 27, and I was still making only $40 a week. My wife had to work too. We made, between us, $80 a week, which kept us afloat. So it was a mixed time. The important thing of any time you live in is to be in love yourself. You float above your time then. It’s what you want that counts, not what your time wants. You grew up as a science fiction/fantasy fan yourself. What is it like now to have fans of your own? Oh, it’s wonderful. I have a lot of children, you know. A lot of honorary sons and daughters. And I get spoiled when I go to conventions or like when I’ll be down in Albuquerque in a couple of days. The love is there. Sometimes when I lecture, before I start, I get a standing ovation—before I say a word! Well, “My god,” I say, “I’m gonna leave right now.” [Laughs.] We all want to be loved. When we’re teenagers we don’t get enough. We’re very lonely. We don’t have a girlfriend or a boyfriend. And when the day comes when you finally have your first big love affair—my god, the world changes. That’s true also when you have a lot of readers. Do you think fandom, as a group, has changed much since your day? No, no. No, they’re all crazy. I’ve been to a lot of conventions. They’re very funny looking. But we were funny looking, too. You’ve had a long and occasionally contentious history with Hollywood. [Laughs] Oh, boy! And how! What do you recall about movies growing up? Do you remember them inspiring you as a child? Oh, I’ve seen every movie ever made. My mother was a maniac for movies. She started taking me to films in 1921 when I was a year old. She carried me into the theater. I saw all the silent movies. I was there when I was seven, when sound was invented with Al Jolson. I’ve seen every important movie, and many of them 15 or 20 times. Do you watch movies nowadays? Oh, yes. But mainly at the end of the year. I don’t like to go to theaters, because I don’t like the way most people behave in theaters. I’m a member of the Academy [of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences], and every January, I get 80 films through the mail. My wife and I have a large 50-inch TV set, so you get a damn good large picture, and then we rent all the best films of the year in January. Of course, there’s a new film version of Fahrenheit 451 in the works right now. Mel Gibson’s company is developing it. I had heard that you’d seen a draft of the screenplay and weren’t too impressed with it. Well, I opened it in the middle. It was sent to me by a bookstore in Atlanta. Gibson’s people didn’t send me any of the screenplays. I wrote the first one and they never reacted to it. They had eight more written. And finally in the mail about eight months ago, a copy of the seventh screenplay reached me through a bookstore in Atlanta. It had been stolen from Warner Brothers, given to the bookstore and they sent it to me. So I opened up the screenplay to, I don’t know, about page 25 and just read that one page, in which the fire chief comes to visit Montag and his wife Mildred. And when the fire chief comes in their house, Mildred says, “Would you like some coffee?” And the fire chief says, “Does a bear shit in the woods?” And I closed the screenplay. Do you believe that? I think that was probably the proper response. Where’s that in my book? Oh, god. So that’s the sort of crud that goes on. They want to be dirty, they want to be salacious, they want to shock you. And, I’m sorry, they don’t do that to me. What did you think of Francois Truffaut’s 1967 version of Fahrenheit 451? It was OK, but there’s a lot of missing things. Mechanical Hound was not there. It has to be there. Faber was not there. [Truffaut] miscast; he had Julie Christie in two roles. That was very confusing. The girl next door’s got to be 16. Julie Christie was not 16. You’ve got to have a naive girl who teaches Montag in her naiveté. She shouldn’t know that she’s teaching. There’s the beauty of the relationship—that Montag, who is ignorant, is taught by a girl who doesn’t know what she’s doing. It’s glorious. I put it on the stage. I’ve done it as an opera and I’ve done a straight play, and you cast a 16-year-old girl there in that part and it’s beautiful. Do you think Hollywood is afraid of writers? Of course they are, that’s why they don’t call. Mel Gibson, I’ve worked with him for three years now. During that whole time, not one phone call and not one letter. Of course they’re afraid of me. It’s funny. I’ve talked to many, many people, and they all say it’s real simple to make one of your books into a movie—just put it on the screen. Sam Peckinpah, 20 years ago, wanted to do one of my books, and I said, “Sam, how do you do it?” And he says, “Rip the pages out of your book and stuff ’em in the camera.” I said, “That’s right!” Everything I write is screen material. We all know the authors you read and admired and on which you built your career. Do you read many current writers? Nope. No, because that’s incestuous. You can’t read in your own field. You’ve got to go to other fields and borrow ideas from Shakespeare and Alexander Pope, or Lorin Eisley the anthropologist or Katherine Ann Porter or Emily Dickenson. You must never read in your own field. You do that when you’re young. I read all of H.G. Welles and Jules Verne and Aldous Huxley. But you can’t continue that, because then you never learn anything. You’ve cultivated a great many—I don’t want to say “hobbies”—but interests, passions, outside the writing field. One of them is architecture. What is it about architecture that attracts you? Well, it’s science fictional, isn’t it? I started falling in love with cities and World’s Fairs when I was a kid. I always dreamt of being part of a World’s Fair. And in 1962, the people in charge of the United States Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair came to my house and asked me to help create the whole top floor of the building. So I got into architecture then. I created a 500-year history of the United States with a narrator and a full symphony orchestra. Later I moved on and did the same thing for Disney’s EPCOT, the Spaceship Earth. Then I designed, I made up imaginary malls for the future, 25 years ago. Some of them have been built. Architects have taken my ideas and, for a while, I was employed by an architectural firm to create the Horton Plaza in San Diego. You not only talk about it, but you build it. That must be a different, more tangible experience than writing. Well, everything is an extension of everything else. And if you’re in love, then you can do it.