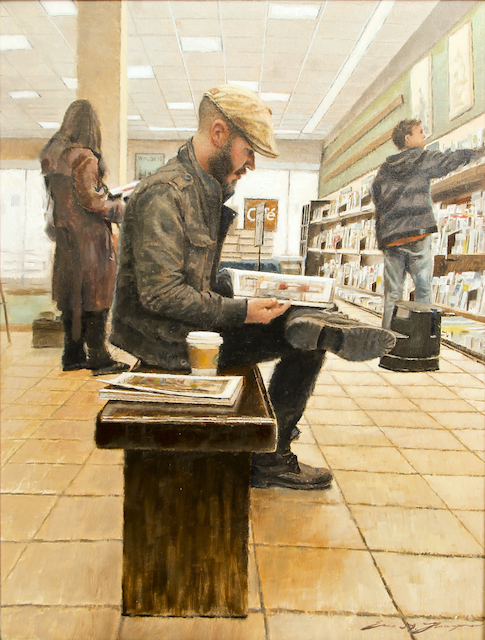

One question contemporary realist painters often get is, “Why not simply take a photograph?” Eric G. Thompson, a self-taught artist who lives in Salt Lake City, Utah, answered this familiar assault with brio the other evening at the opening of his show at Matthews Gallery in Santa Fe (669 Canyon Road). He explained that what photographs can’t replicate is the energy contained in a painting. Thompson’s aim—to “capture an emotion in time”—expresses itself in every well-placed brushstroke he applies to the canvas. Even the familiar chalk-white Starbucks cup with its green logo and little brown sleeve in his painting “The Photographer” bristles with personality. Or consider the oversized greenish ceramic mug in “Morning Cup,” crosshatched with points of light. “Objects have spirit,” Thompson said. “An old cup is like a person.”Thompson likes to call his paintings “visual haikus,” which spurred the Matthews Gallery to display snippets of great American poetry in the exhibit, samples from poets including Emily Dickinson, Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Lowell and Robert Frost.A good example is Robert Lowell’s “Epilogue” paired with the painting “Coffee Shop Girl.” Lowell writes: “I hear the noise of my own voice:/ The painter’s vision is not a lens,/ it trembles to caress the light” [emphasis original]. These lines are reflected in the Coffee Shop Girl’s illuminated face—as pale as rice paper. Later on, the poem continues: “Pray for the grace of accuracy/ Vermeer gave to the sun’s illumination/ stealing like the tide across a map/ to his girl solid with yearning.” Though large sunglasses hide her face and her meager mouth is expressionless, the Coffee Shop Girl is ravenous. We see her frayed emotional state in the feathery brushstrokes in the background, the squirming reddish-brown tendrils of her ponytail, and the sparkling clusters of dandelion-like fur attached to the hood of her puffy coat.In a similar way, Robert Frost’s “A Boundless Moment” provides a context for Thompson’s painting “Spring City House.” The first lines of Frost’s poem mirror the quiet loneliness of the house: “He halted in the wind, and—what was that/ Far in the maples, pale, but not a ghost?” The broken teeth of a destroyed fence in the painting’s foreground of give the ghost-like house a forlorn feel. The house’s surface is a clear expanse of creamy off-white dimpled with tiny pinpricks. Its eyelike window is dark: No one is home. To the right of the house, there’s a hint of promise in the glimpse of a yellow field, tempered by the stillness of an abandoned chair on the porch next to it.Thompson’s “The Photographer” places us in an anemic yellow light (not the usual harsh florescent shine) of the magazine section of a Barnes & Noble. The Photographer—a strapping bearded guy in a cap and hefty boots—appears mesmerized by a heavy magazine open on his lap. He seems alone in his thoughts. Two other people, turned away from him, are also engrossed in their reading, sampling something very private in a public space. An Emily Dickinson poem posted next to the painting “Evening Glow” opens: “Ah, Moon—and Star!/ You are very far—/ But were no one/Farther than you—/ Do you think I’d stop/ For a Firmament—/ Or a Cubit—or so?” In “Evening Glow” the branches of trees claw in every direction as the moon recedes into the background of a steel-colored sky. There is a quiet sadness in the warm, flickering light of a cottage window, as the viewer is on the outside looking in … so far away. “Why not simply take a photograph?” How else to give voice to our common predicament than with oil, egg tempera and watercolor or with the pen and ink of our best American poets? In the end, we are not always lonely, but forever alone.

The Boundless Moment: New Paintings by Eric G. ThompsonRuns through Thursday, Aug. 28Matthews Gallery669 Canyon Road, Santa Fethematthewsgallery.com, (505) 992-2882Hours: Monday-Saturday, from 10am to 5pm, and Sunday, 11am to 4pm