Of Bertha West, who was my friend in college and after, in life, I can speak only with extreme terror. This terror is not due altogether to the sinister manner of her recent disappearance, but was engendered by the whole nature of her life-work, and first gained its acute form more than 17 years ago, when we were in the third year of our course at the University of New Mexico Medical School in Albuquerque. While she was with me, the wonder and diabolism of her experiments fascinated me utterly, and I was her closest companion. Now that she is gone and the spell is broken, the actual fear is greater. Memories and possibilities are ever more hideous than realities.The first horrible incident of our acquaintance was the greatest shock I ever experienced, and it is only with reluctance that I repeat it. As I have said, it happened when we were in the medical school, where West had already made herself notorious through her wild theories on the nature of death and the possibility of overcoming it artificially. Her views, which were widely ridiculed by the faculty and her fellow-Lobos, hinged on the essentially mechanistic nature of life; and concerned means for operating the organic machinery of mankind by calculated chemical action after the failure of natural processes. In her experiments with various animating solutions, she had killed and treated immense numbers of jackrabbits, prairie dogs, cats, dogs and roadrunners, till she had become the prime nuisance of the college. Several times she had actually obtained signs of life in animals supposedly dead; in many cases violent signs; but she soon saw that the perfection of this process, if indeed possible, would necessarily involve a lifetime of research. It likewise became clear that, since the same solution never worked alike on different organic species, she would require human subjects for further and more specialized progress. It was here that she first came into conflict with the college authorities, and was debarred from future experiments by no less a dignitary than the dean of the medical school himself—the learned and benevolent Dr. Allan Halsey, whose work on behalf of the stricken is recalled by every old resident of Albuquerque.I had always been exceptionally tolerant of West’s pursuits, and we frequently discussed her theories, whose ramifications and corollaries were almost infinite. Holding with Haeckel that all life is a chemical and physical process, and that the so-called “soul” is a myth, my friend believed that artificial reanimation of the dead can depend only on the condition of the tissues; and that unless actual decomposition has set in, a corpse fully equipped with organs may with suitable measures be set going again in the peculiar fashion known as life. That the psychic or intellectual life might be impaired by the slight deterioration of sensitive brain-cells which even a short period of death would be apt to cause, West fully realized. It had at first been her hope to find a reagent which would restore vitality before the actual advent of death, and only repeated failures on animals had shown her that the natural and artificial life-motions were incompatible. She then sought extreme freshness in her specimens, injecting her solutions into the blood immediately after the extinction of life. It was this circumstance which made the professors so carelessly skeptical, for they felt that true death had not occurred in any case. They did not stop to view the matter closely and reasoningly.It was not long after the faculty had interdicted her work that West texted me her resolution to get fresh human bodies in some manner, and continue in secret the experiments she could no longer perform openly. To see her messages discussing ways and means was rather ghastly, for at the university we had never procured anatomical specimens ourselves. Whenever the morgue proved inadequate, two mysterious local hipsters attended to this matter, and they were seldom questioned. West was then a small, slender, bespectacled young woman with delicate features, bleached yellow hair, pale translucent skin showing blue veins, wide hazel eyes and a soft velvety voice, and it was uncanny to hear her dwelling on the relative merits of Fairview Memorial Park Cemetery versus the Mt. Calvary potter’s field across from Albuquerque High School. We finally decided on the Mt. Calvary potter’s field, because practically every body in Fairview was embalmed; a thing of course ruinous to West’s researches.I was by this time her active and enthralled assistant, and helped her make all her decisions, not only concerning the source of bodies but concerning a suitable place for our loathsome work. It was I who thought of the deserted Gonzalez farmhouse beyond Nine Mile Hill, where we fitted up on the ground floor an operating room and a laboratory, each with dark curtains to conceal our midnight doings. The place was far from any busy road and in sight of only distant cookie-cutter houses on the West Side, yet precautions were nonetheless necessary, since rumors of strange lights, started by chance nocturnal roamers, would soon bring UFO hunters on our enterprise. It was agreed to call the whole thing an abandoned meth lab if discovery should occur. Gradually we equipped our sinister haunt of science with materials either purchased in El Paso or quietly borrowed from the university—materials carefully made unrecognizable save to expert eyes—and provided shovels and picks for the many burials we should have to make in the cellar. At the university we used an incinerator, but the apparatus was too costly for our unauthorized laboratory. Bodies were always a nuisance—even the jackrabbit bodies from the slight clandestine experiments in West’s room at the dorms.We followed the local obituaries like ghouls, for our specimens demanded particular qualities. What we wanted were corpses with no family to claim them, interred soon after death and without artificial preservation; preferably free from malforming disease, and certainly with all organs present—quite difficult in the age of organ donation. Newcomers to our “land of enchantment” were our best hope. Not for many weeks did we hear of anything suitable; though we talked with morgue and hospital authorities, ostensibly in the university’s interest, as often as we could without exciting suspicion. We found that the university had first choice in every case, so that it might be necessary to remain in Albuquerque during the summer, when only the limited summer school classes were held. In the end, though, luck favored us; for one day we heard of an almost ideal case in the Mt. Calvary potter’s field; a brawny young construction worker drowned only the morning before in the Rio Grande, and buried at the city’s expense without delay or embalming. That afternoon we found the new grave, and determined to begin work soon after midnight.It was a repulsive task that we undertook in the black small hours, even though we lacked at that time the special horror of graveyards which later experiences brought to us. We carried shovels and dim camping lanterns, for although we could have relied on the flashlights from our cellphones, they would have been too bright and called the attention of nearby residents. The process of unearthing was slow and sordid—it might have been gruesomely poetic if we had been artists instead of scientists—and we were glad when our shovels struck wood. When the pine box was fully uncovered, West scrambled down and removed the lid, dragging out and propping up the contents. I reached down and hauled the contents out of the grave, and then we both toiled hard to restore the spot to its former appearance—not particularly arduous in the dusty, grassless turf. The affair made us rather nervous, especially the stiff form and vacant face of our first trophy, but we managed to remove all traces of our visit. When we had patted down the last shovelful of chalky earth, we put the specimen in a large canvas duffel bag, tossed it in the truck bed of my beat-up ’95 Datsun, and set out for the old Gonzalez place beyond Nine Mile Hill.On an improvised dissecting-table (a stained beer pong table smuggled from the nearest frat house) in the old farmhouse, by the light of a powerful LED lamp, the specimen was not very spectral looking. It had been a sturdy and apparently unimaginative guy of wholesome plebeian type—large-framed, suntanned, gray-eyed and brown-haired—a sound animal without psychological subtleties, and probably having vital processes of the simplest and healthiest sort. Now, with the eyes closed, it looked more asleep than dead; though the expert test of my friend soon left no doubt on that score. We had at last what West had always longed for—a real dead man of the ideal kind, ready for the solution as prepared according to the most careful calculations and theories for human use. The tension on our part became very great. We knew that there was scarcely a chance for anything like complete success, and could not avoid hideous fears at possible grotesque results of partial animation. I felt a clammy shiver crawl up my spine at the mental image of a live hand attached to a dead body. Especially were we apprehensive concerning the mind and impulses of the creature, since in the space following death some of the more delicate cerebral cells might well have suffered deterioration. I, myself, having been raised Catholic by a fearsomely religious grandmother, still held some curious notions about the traditional “soul” of man, and felt an awe at the secrets that might be told by one returning from the dead. I wondered what sights this placid young man might have seen in inaccessible spheres, and what he could relate if fully restored to life. It was the chance to converse with Lazarus. But my wonder was not overwhelming, since for the most part I shared the materialism of my friend. She was calmer than I as she forced a large quantity of a viscous, electric green fluid into a vein of the body’s arm, immediately binding the incision securely.The waiting was gruesome, but West never faltered. Every now and then she applied her stethoscope to the specimen, and bore the negative results philosophically. After about three-quarters of an hour without the least sign of life she disappointedly pronounced the solution inadequate, but determined to make the most of her opportunity and try one change in the formula before disposing of her ghastly prize. We had that afternoon dug a grave in the cellar, and would have to fill it by dawn—for although we had fixed a lock on the house, we wished to shun even the remotest risk of a ghoulish discovery by transients or wayward teenagers. Besides, the body would not be even approximately fresh the next night. So taking the solitary LED lamp into the adjacent laboratory, we left our silent guest on the beer pong table in the dark, and bent every energy to the mixing of a new solution; the weighing and measuring supervised by West with almost fanatical care.The awful event was very sudden, and wholly unexpected. I was pouring something from one test tube to another, and West was busy over the chef’s butane torch which had to answer for a Bunsen burner in this gasless edifice, when from the pitch-black room we had left there burst the most appalling and demoniac succession of cries that either of us had ever heard. Not more unutterable could have been the chaos of hellish sound if The Pit itself had opened to release the agony of all the damned basketball and football players in UNM’s history, for in one inconceivable cacophony was centered all the supernal terror and unnatural despair of animate nature. Human it could not have been—it is not in man to make such sounds—and without a thought of our late employment or its possible discovery, both West and I leapt to the nearest window like stricken animals; overturning tubes, lamp, torch and retorts, and vaulting madly into the warmed, starred abyss of the desert night. I think we ourselves screamed as we stumbled frantically toward the city, though as we reached the outskirts we put on a semblance of restraint—just enough to have the presence of mind to call an Über, seeming to our driver like belated revelers staggering home from a house party.We did not separate, but managed to get to West’s room at Hokona Hall, where we whispered with the lights on until dawn. By then we had calmed ourselves a little with rational theories and plans for investigation, so that we could sleep through the day—classes being disregarded. But that evening two items in the local daily newspaper, wholly unrelated, made it again impossible for us to sleep. The old deserted Gonzalez house had inexplicably burned to an amorphous heap of ashes; that we could understand because of the upset butane torch. Also, an attempt had been made to disturb a new grave in the Mt. Calvary potter’s field, as if by futile and shovel-less clawing at the earth. That we could not understand, for we had patted down the mould very carefully.And for 17 years after that, West would look frequently over her shoulder, and complain of fancied footsteps behind her. Now she has disappeared.

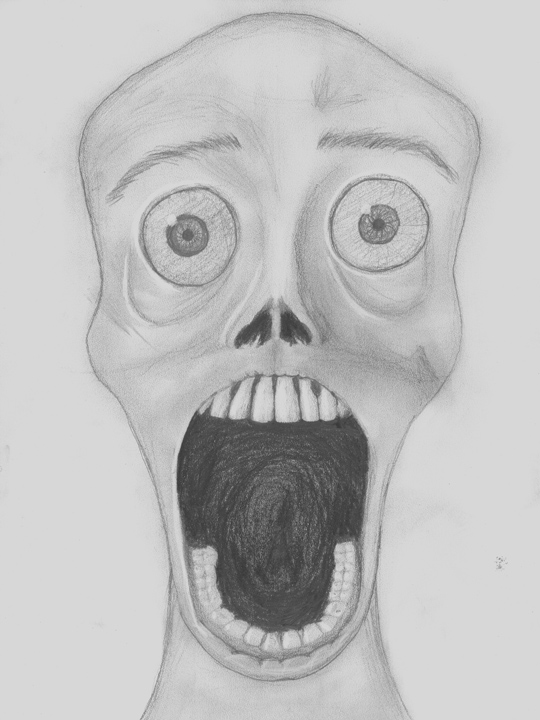

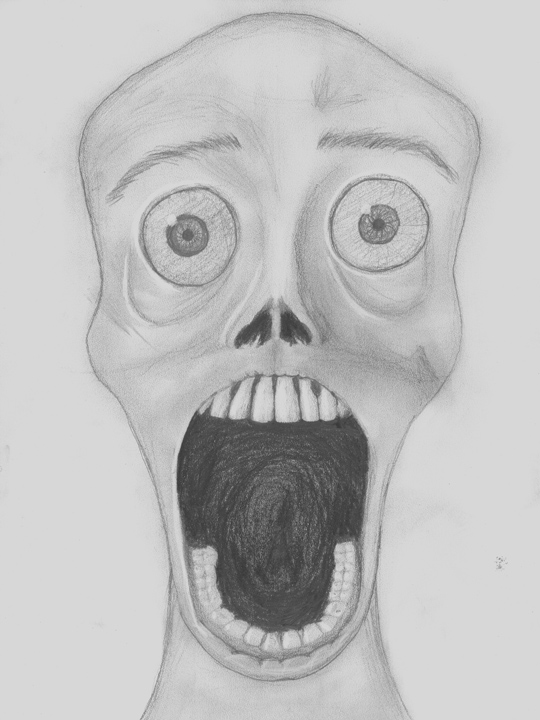

“Memories and possibilities are ever more hideous than realities.”