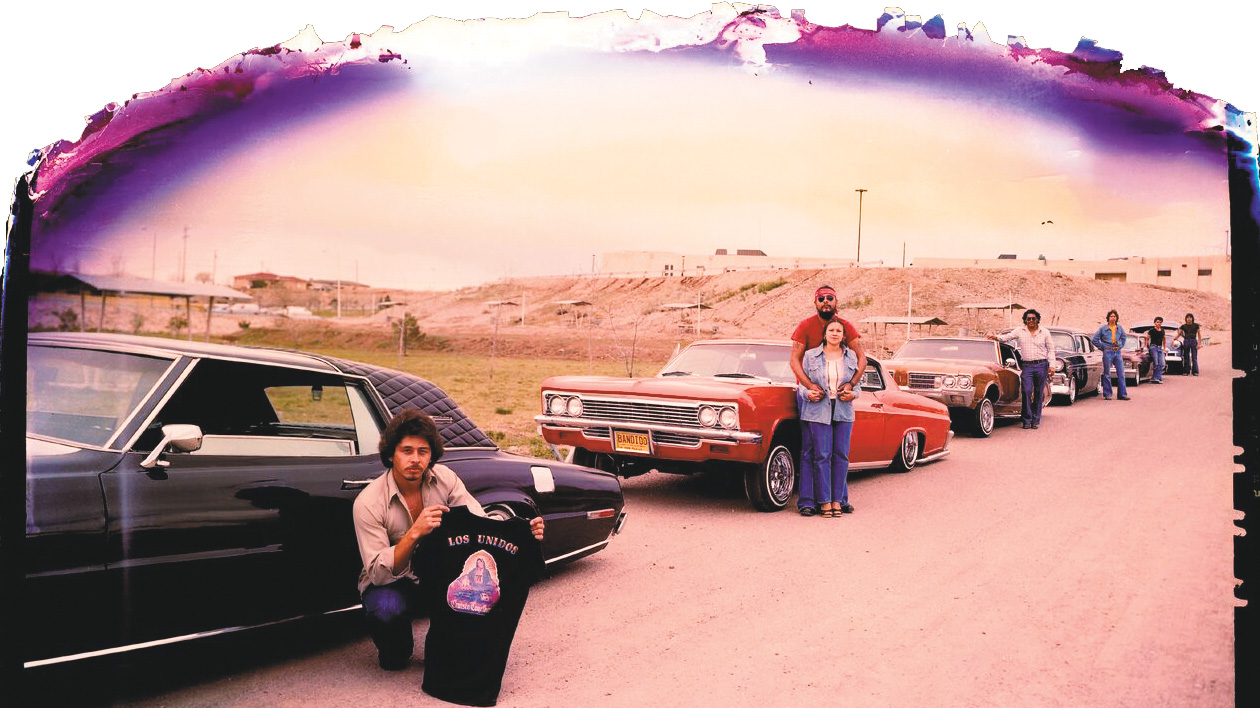

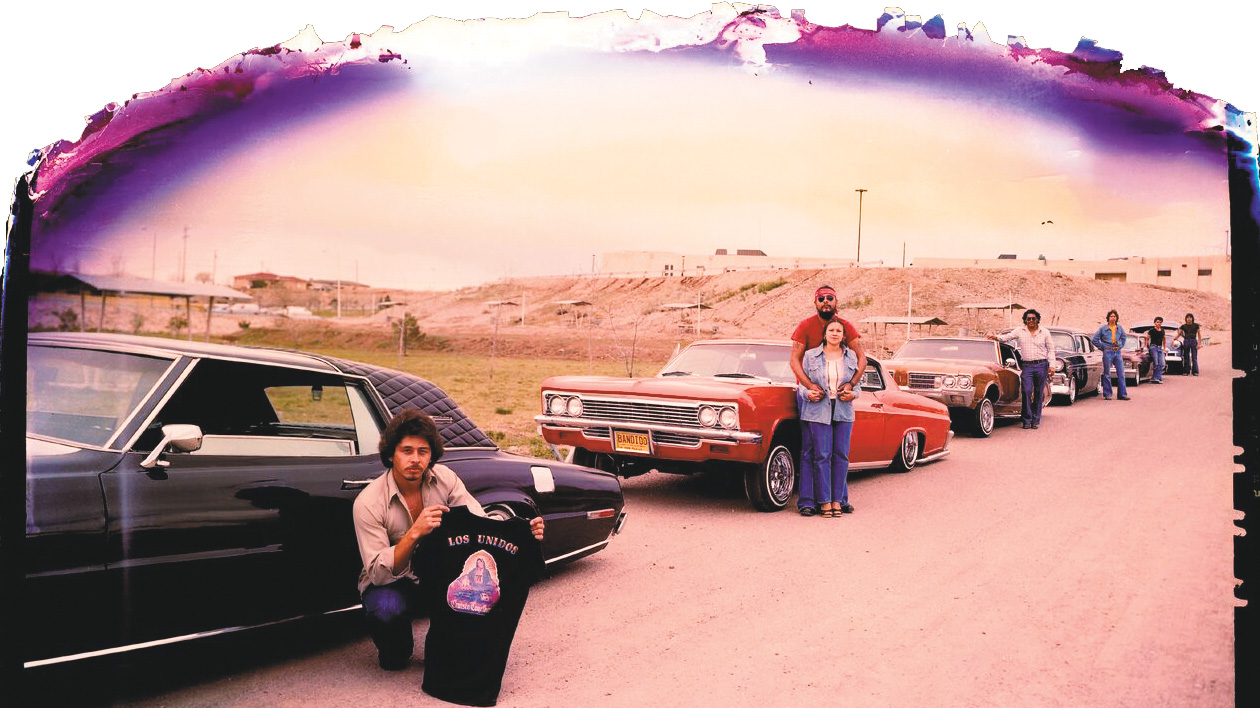

Lowriders

Talking Lowriders In New Mexico With Writer And Photographer Don Usner

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992