Bird Of Prey

Introducing The Novint Falcon

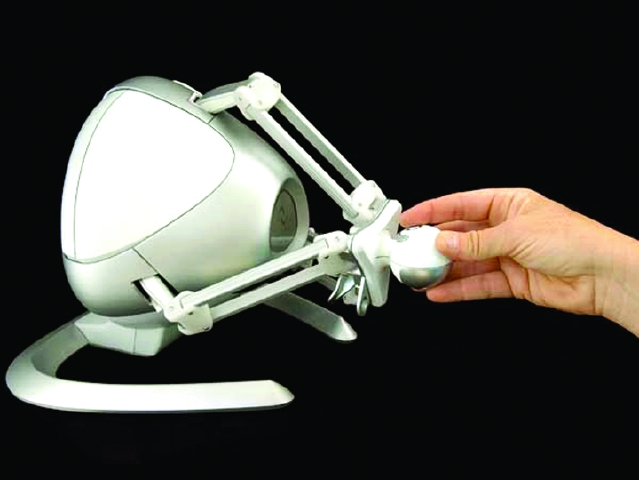

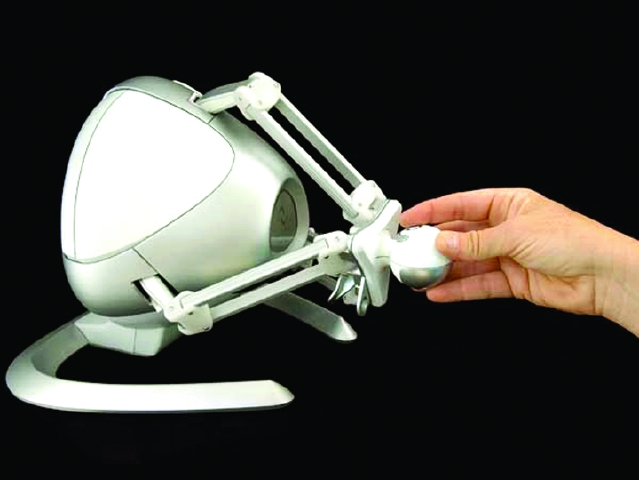

Careful! You could put an eye out with that thing.

Courtesy of Novint Technologies, Inc.

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Careful! You could put an eye out with that thing.

Courtesy of Novint Technologies, Inc.