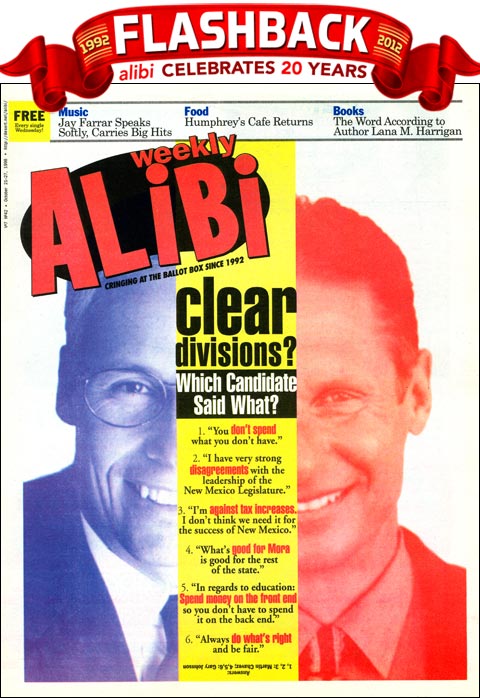

Alibi Flashback: Marty Chavez Vs. Gary Johnson

Or, “Nasty Vs. Flaky”

David Lineberger

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

David Lineberger