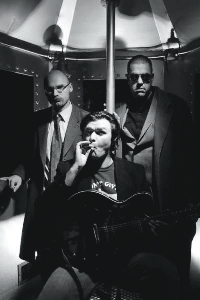

Derek Miller

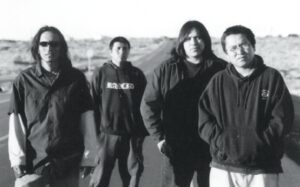

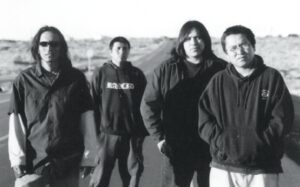

Keith Secola

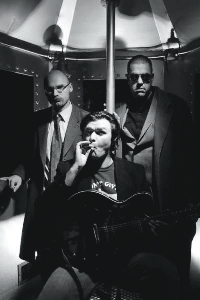

The Old Main

Rocking Horse

Saving Damsels

Coalition

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992