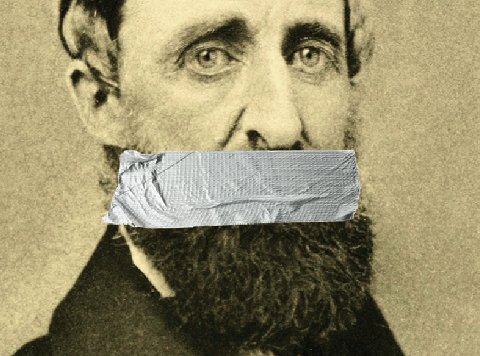

Spring is a time of rebirth: a season suspended between the end of winter’s suffering and the beginning of summer’s warmth. This is true everywhere except Albuquerque, where spring brings fear and anxiety. It’s our season of dry wind and relentless drought. This Albuquerque Spring offers no escape from that cruel pattern. But our suffering is not defined by the axial tilt of the earth as it races around the sun, but rather by a culture of violent policing that seems just as inevitable. Albuquerque Spring began early, on March 16, when James Boyd, homeless and suffering from schizophrenia, hiked the Copper Trailhead seeking a safe place to sleep. But amid the beauty of the Sandias, just beyond the wealthy neighborhoods of the Foothills, he found an aggressive police response to his presence. After a four-hour standoff with APD, he died in a barrage of gunfire and flashbang grenades. Millions have seen that shocking video by now. Boyd’s violent death, and Police Chief Gorden Eden’s deranged claim that officers’ fatal shooting of a mentally ill, homeless man was justified, resurrected old fears that a long history of police violence was gathering new momentum. Anger and grief brought a thousand people into Albuquerque streets on March 25. But just hours after protesters marched to condemn police violence, APD shot and killed Alfred Redwine. An eyewitness video showed Redwine holding a cellphone when APD officers opened fire. APD claimed Redwine fired a weapon at officers, but no lapel camera video exists to confirm this claim. Another march followed another person’s death. APD responded with urban assault vehicles, combat-equipped SWAT units, a squad of ominous-looking mounted police, K9 units and riot police who fired tear gas at protesters. That militarized response to a peaceful protest brought national and international media to Albuquerque; they struggled to explain what was happening here. It didn’t take long for an official explanation. On April 10, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) ended its nearly two-year investigation of APD with a 46-page findings letter on APD’s use of excessive force. Boyd was not an exception, and APD routinely uses unjustified, unconstitutional lethal force. The problem begins at the top, where APD brass fosters a climate of violent, crisis-mode policing in which officers are free to use force with impunity.The next day Mayor Richard Berry hired Tom Streicher to represent the city in negotiations with the DOJ over federally mandated reforms. Streicher is the former chief of the Cincinnati Police Department. In April 2001, a Cincinnati police officer shot and killed an unarmed 19-year-old black man named Timothy Thomas. Streicher refused to release information about the shooting. Thomas was the 15th young black man killed by Cincinnati police in six years. Rioting broke out in African-American neighborhoods terrorized by decades of police violence. The mayor called in the DOJ. That investigation produced an April 2002 agreement that Streicher routinely flouted. He blocked monitors at every step and frequently violated the agreement. Streicher, the chief of a police department that routinely engaged in violent racialized policing, with documented experience in evading DOJ-imposed remedies to unconstitutional policing will now represent Albuquerque in negotiations with the DOJ.On April 15 three members of the Police Oversight Commission resigned in protest. Jonathan Siegel wrote that he “cannot continue to pretend or deceive the members of our community into believing that our city has any real civilian oversight.” Jennifer Barela also resigned. “I will not mislead the citizens of Albuquerque into believing that our City has any civilian oversight.” Richard Shine followed, complaining that obstruction from the City Attorney’s Office “makes a complete and final sham of any meaningful civilian oversight of police in Albuquerque. I refuse to contribute to the deception of the public by continuing to serve on the POC.” One week later Jeremy Dear killed 19-year-old Mary Hawkes. APD claimed Hawkes had a gun and the officer fired in self-defense. The gun has never been produced, and no lapel camera video of the shooting exists. Eyewitnesses recounted a harrowing story of her final hours. APD hunted the homeless teenager after she allegedly broke into a truck to find safety in the night. Hawkes had no violent criminal history, but APD sent an army into the streets after her. They tracked her to a mobile home park where they released dogs as police cruisers blared warnings from loudspeakers. Dear shot her to death on the sidewalk.The DOJ concluded that the problems at APD were not only about excessive force, but also a function of serious failures in leadership. On April 23 KRQE reporters obtained months of emails between Former APD chief Ray Schultz and representatives of Taser, a company that manufactures electroshock weapons and lapel cameras. A week before his retirement in 2013, Taser offered Schultz a lucrative job offer: “Is consulting something you’d consider?” Schultz replied he was interested and also that he’d cleared a path for Taser to receive a no bid, multimillion dollar contract with APD to provide weapons and lapel cameras. “Everything has been greased,” he wrote Taser, “so it should go without any issues.” Taser collects former police chiefs like a child collects baseball cards. Streicher, too, is on their payroll.APD SWAT killed Armand Martin on May 3. DOJ says that APD’s SWAT Unit suffers from serious deficiencies that contribute “to the pattern of unreasonable use of force.” It deals poorly with subjects who are suicidal, barricaded or suffering from mental health crises. All of which were on display in the death of Martin, a 50-year-old Air Force veteran. Armed and suicidal, Martin barricaded himself in his house. SWAT spent hours blasting warnings by loudspeaker at him while combat-equipped officers swarmed his home. They fired flashbang grenades, a weapon designed to shock and disorient, through the windows. Martin fled the barrage, and he was shot to death as he exited the house. APD claimed Martin fired at officers with two handguns, but the only video of the encounter shows APD officers handcuffing a dying Martin. Armand Martin’s brother Tommy was talking to his brother by phone moments before he was killed. The cellphone is visible in the video of officers handcuffing Martin, contradicting APD claims that Martin fired two guns. Tommy Martin is still waiting for the results of his brother’s autopsy. In preliminary conversations, Martin says the coroner found no gunfire residue on his brother’s hands. A coalition of activists and family members of victims of police violence, including myself, held a vigil for Martin. There we decided to launch a campaign of civil disobedience. At the City Council meeting on May 5, 40 people stood at the podium as I read a collectively written statement that included the following section: “Tonight, in the true spirit of democracy and with the seriousness to which it deserves and with the power given by the people of New Mexico and its courts of law, we now serve a people’s warrant for the arrest of Albuquerque Police Chief Gorden Eden, who is charged as an accessory after the fact in the second-degree murders of James Boyd, Alfred Redwine, Mary Hawkes and Armand Martin.”Eden and his entourage fled the chambers while most City Councilors abandoned their chairs. Council President Ken Sanchez cancelled the meeting. Protesters took their seats, and we held a “People’s Assembly.” Three days later, under new restrictions on free speech, Sanchez ordered that police forcibly remove seven people, of whom I was one, for standing in silent protest against City Council inaction.The killing continued. APD killed Ralph Chavez on May 22. Chavez, who had a long history of violence and mental illness, was killed after he attacked a woman and slashed a good samaritan who came to her defense. APD officers found a suicidal Chavez holding a small box cutter. They shot him to death from 20 feet away. No video of the shooting exists.We turned our attention to Mayor Berry. On June 2, 32 people, including family members of victims of police violence, walked into the office of Mayor Berry to stage a sit-in. APD’s SWAT unit swarmed the building in a show of force consistent with DOJ criticisms of APD’s culture of aggressive policing. Thirty riot police arrested 13 peaceful protesters.On Monday, June 9, Eden placed a gag order on police and civilian employees of APD banning them from talking to the DOJ. Later that day the City Council placed more restrictions on public comment. Councilor Diane Gibson declared herself “a defender of free speech and the right to speak openly,” moments before voting to limit free speech and the right to speak openly.The next day the District Court found in favor of the family of Christopher Torres in a lawsuit against the City and awarded the family $6 million. In April 2011 two APD detectives shot an unarmed Torres three times in the back. Just four months after District Attorney Kari Brandenburg declared the shooting justified, a judge disagreed, “Detectives Brown and Hilger’s testimony is inconsistent with the eyewitness’ testimony and the physical evidence.” In an interview last week, Renetta Torres, Christopher Torres’ mother, criticized Berry, the Council and APD for offering little more than “cosmetic changes.” Real change comes not from individuals but rather, like the seasons, from forces larger than us. Our Albuquerque Spring will end this Saturday, June 21, on the summer solstice, when thousands will gather in Roosevelt Park at 11am for a March to End Police Brutality. And a spring that began with horror will end with hope. But as Torres told the press last week, “We’ve only just begun.”