Back To The Future

An Interview With The Fountain Director Darren Aronofksy

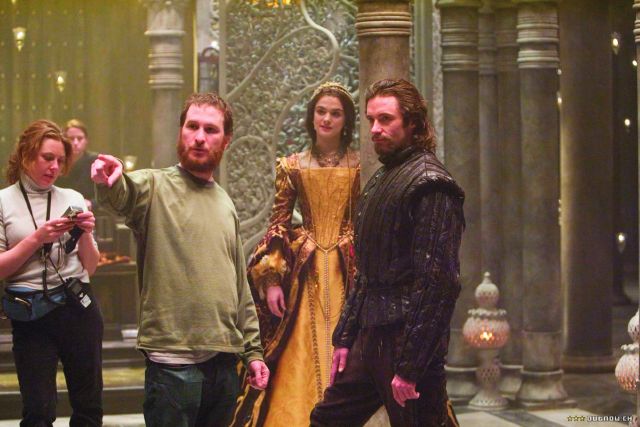

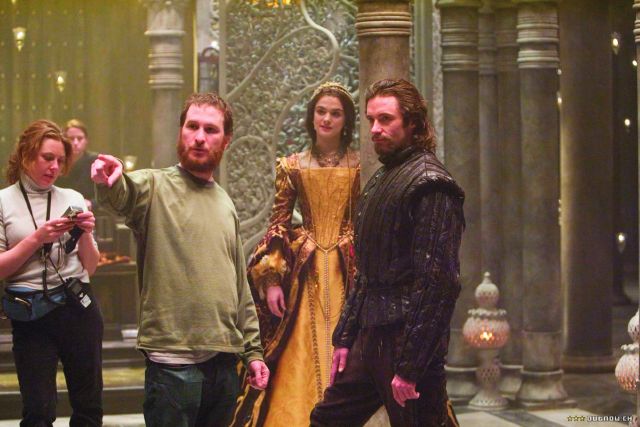

Snowglobes in space.

An example of The Fountain’s trippy production design.

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

Snowglobes in space.

An example of The Fountain’s trippy production design.