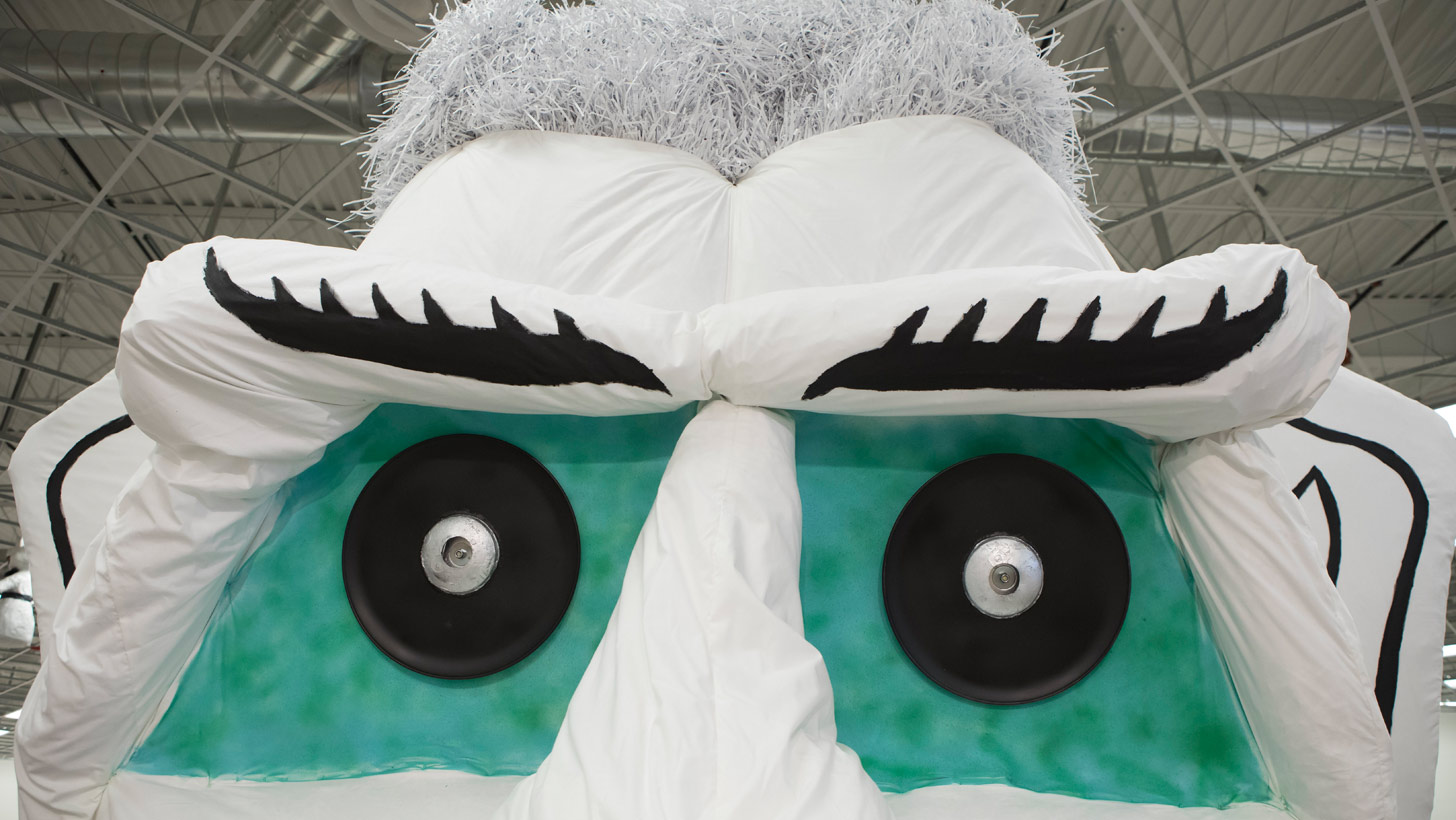

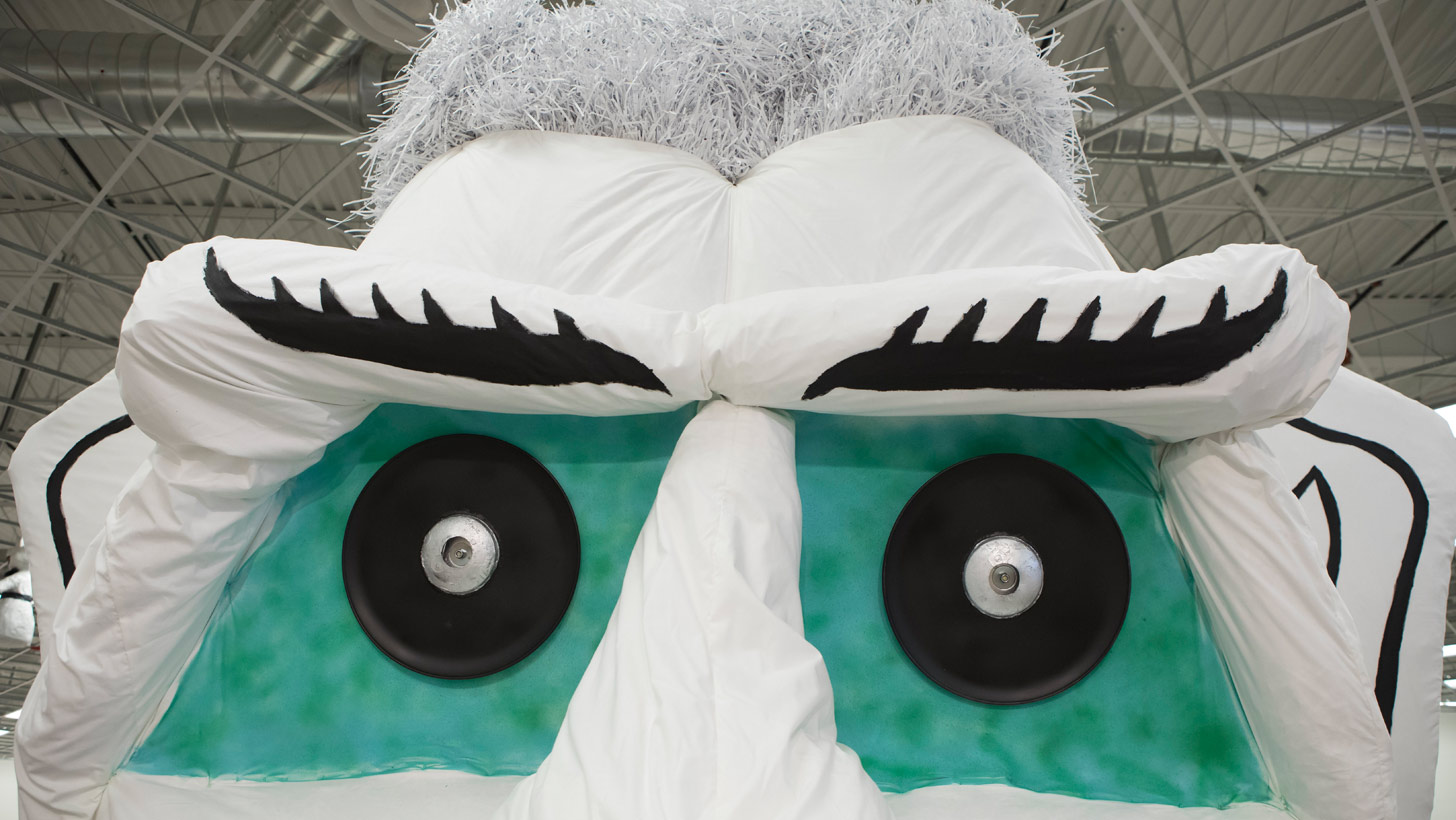

If you dwell in the 505, chances are you have a story about Zozobra.Maybe you even have more than one. Every time that part of the year rolled around, when the hot summer seemed to be ebbing here in Burque, my father would pack the family car with the customary accoutrements of a great American road trip and we would roll up to Santa early—like the Thursday night or Friday morning before the burn—and rent a room at the Inn of the Governors.Back then, the burning of Zozobra signified the beginning of the Santa Fe Fiestas. That’s not true anymore, and there is a week-long gap now between the two storied events.But Zozobra was created with the Fiestas in mind—as both alternative and addition to the celebration of la reconquista del norte—by a local artist named Will Shuster. Shuster believed the addition of a marionette, to be burnt up along with the year’s fears and regrets, would add to the joyful but solemn conquering narrative propagated by officials since the commemorative event began in the 18th century. Zozobra, named by the local newspaper editor, was first presented to the community in 1924.The two events diverged in the late-1990s though, after a deadly shooting following the burning led city officials to separate the two events, first by moving the rite of Zozobra back to the Thursday before la entrada and then, in 2014, returning the event to its Friday night status, albeit a week before Fiestas actually begin.Throughout the history of this relatively nuevo nuevo mexicano tradition, the always-to-be-burnt-effigy has always been within the ken of the Santa Fe Kiwanis Club. From conception to promotion, from construction to destruction, the Kiwanis represent Shuster’s legacy.Weekly Alibi sought out that semi-sacred source and met with the humans behind the popular yearly ritual, including Ray Sandoval, the chairman of the Kiwanas Club of Santa Fe, as well as two of the artisans involved in the puppet’s construction, Jacob Romero and Scott Wiseman.Weekly Alibi: How long have you been working with Zozobra?Ray Sandoval: Since I was 6 years old, so 38 years. For me it all started in kindergarten. They assigned show and tell, and so I went and looked in the phone book, found the number for the Kiwanis Club and called. Scott Griffin, who was club secretary at the time answered the phone. He told me that he and Harold Gans (the voice of Zozobra) would come to my school and talk to my class for show and tell. They showed up the next day and gave a presentation. I got in trouble. But I’ve been fighting the Zozobra bug ever since.Jacob Romero: I have been working on Zozobra for 17 years. I started at the age of 8 years old volunteering with the annual event. The first task that I was ever given by the late Harold Gans (former voice of Zozobra and construction supervisor) was to stand on the end of a piece of poultry netting so he could roll out the wire and it would not roll back. At the time I didn’t know what the poultry netting was for. This would become one of four pieces of netting to be placed on top of the skeleton of his body to make his iconic shape. This poultry netting is then stuffed with shredded paper.Scott Wiseman: I have been involved in Zozobra since age 11. My parents surprised me over dinner one night when they announced they had enrolled me in the gloomy audition. I was accepted and participated in the performance for three years, and even one the costume contest two times! This opened the door to many opportunities to help stuff Zozobra with paper. When Kiwanis members caught wind of my unusual level of excitement for Zozobra, I was invited to work on other tasks: making his lips or hair, and eventually his hands.Ray, what’s really kept you involved with Zozobra all these years?Ray Sandoval: I have to be very honest with you. You get to play with fire and burn a 50 foot effigy in the middle of downtown Santa Fe. But the other thing is that I feel like I am the keeper of an important tradition. Zozobra is really important to our community, to our culture. When you add the Kiwanis component, the charitable component—this is our major yearly fundraiser—I really feel like I am giving back to the city.Jacob, as the guardian and executor of the Zozobra blueprints, can you tell our readers about the tools and processes you use?Zozobra is primarily constructed with 2×4 and 1×4 lumber, 12-gauge and 9-gauge tension wire, 2-inch poultry netting and stucco gauge poultry netting. The poultry netting is then stuffed with hundreds of pounds of shredded paper that serves as the accelerant for when he meets his fiery fate. All of that is then covered with a custom made and Zozobra-sized cotton sheet that Kiwanis Club members help sew together yard by yard. There are many other materials that we use to build the Old Man that help bring everything together.The armature which is Zozobra’s skeleton is made of 4 main components. The 2 arms, the head and body are each assigned to a different construction member. After the skeleton is completed, it is connected with tension wire and is covered with 2-inch poultry netting that is braided together with the existing wire so it then forms one solid unit of wood and wire. Scott, Zozobra’s hands and facial features are very important parts of the whole concept, what’s that about? Scott Wiseman: I have been responsible for sculpting Zozobra’s hands since 2008. I’m very meticulous in every project I take on, especially artistic ones. Over the years I’ve been involved with Zozobra, I transformed the marionette’s hands from very crude-looking boxes and cylinders to the three-dimesional sculptural pieces people know today.The construction of the hands is a very non-intuitive process that took years to perfect. I don’t use any typical art supplies. Rather, they are formed out of segments of welded fence material and stucco netting. In order to get the form I want, the fingers have to be individually crafted. Wire ends are twisted together, and a special type of metal clip called "hog rings" also help to keep pieces together. Only a specific type of plier can crimp these clips together. Once the wire mesh is completed, two layers of muslin cloth are wrapped around every detail of the hands and pinned in place by more hog rings. The next step is to paint the lines in the knuckles and fingernails. Finally, the hands are attached to the arms. How is Zozobra different every year?The most obvious difference with Zozobra every year is his hair color, and it is kept secret until the day of the burning. The Decades Project [a Kiwanis project that involves designing Zozobra to reflect various decades in Santa Fe’s history] has given us an opportunity to add other surprises. One year he was shirtless, another he had a potbelly, two years ago he sported a fedora, and last year a cardigan. What will the surprise be this year? You’ll have to find out for yourself on Friday, Aug. 31, August!

The 94th Annual Burning of Zozobra

Friday, Aug. 31 • Fort Marcy Park, Santa FeGates open at 4:30pm • Tickets at burnzozobra.com/tickets