The Barrio Land Grab

Los Martincitos

Ilene Style

Ilene Style

Ilene Style

Ilene Style

Ilene Style

Ilene Style

Ilene Style

Ilene Style

The Work Of Hermana Jacci

Hermana Jacci (bottom right) and a few of the Los Martincitos abuelas

Ilene Style

Hermana Jacci (bottom right) and a few of the Los Martincitos abuelas

Ilene Style

Passover In Peru

Seder In Lima

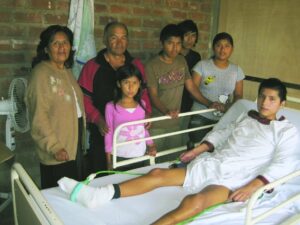

Pablo

Pablo y su familia

Ilene Style

Pablo y su familia

Ilene Style

Petrona

Petrona’s granddaughter poses with her most prized possession, a Barbie backpack.

Ilene Style

Petrona’s granddaughter poses with her most prized possession, a Barbie backpack.

Ilene Style

English Lessons

Voluntaria Margaret teaches English to los niños.

Ilene Style

Voluntaria Margaret teaches English to los niños.

Ilene Style

To ride in a mototaxi is to toy with your life.

Ilene Style

To ride in a mototaxi is to toy with your life.

Ilene Style

Adios, Peru

“If you don’t do something that you’ve never done before, your worldview will be too limited to inspire real change.”—Steven Covey My e-mail list grew exponentially as friends kept asking me to add people after they started receiving my updates from Peru. The question I was asked the most was: How can I help? Most gratifying of all was that so many of my e-mail recipients did help by donating to Los Martincitos. The senior center was so short on funds a few months ago that they almost had to close. Thank you, amigos, for preventing this from happening.Volunteering is a wonderful way to give of yourself. It teaches you that your value does not lie in how much money you make, who you know or what office you hold. Contributing to a fellow human teaches you empathy on a whole new level. Improving another life is not only a gift to that person, but to you. You may not save the world by volunteering, but you will absolutely touch a soul.