"It’s Feeling to Me Like I Wasn’t There"

District Attorney Kari Brandenburg calls Robert Gonzales’ confession "chilling,” though she says she hasn’t seen the entirety of the two interrogation videos that together last more than two-and-a-half hours.*Detectives Brian Sanchez and Mike Marquez pal around with a small, meticulously dressed, vato-looking Gonzales throughout the videos. At about minute 24, Gonzales asks his interrogators, "Is it anything bad that I did?" They tell him they’re investigating a child-abuse crime. At no point does Gonzales request a lawyer. He’s eager to please them. Still, over the course of the hours, even as his mental state grows weary, he insists that he didn’t know Sandoval, that he’d never been to the Westgate trailer park where she died. The detectives take a break and leave Gonzales in the room alone. "I’m fucked," he says to himself. "I’ve never been in that area."They return and ask for details, pulling Gonzales step by step through the events of the attack. Detective Marquez tells Gonzales that something happened, something went wrong, that it wasn’t the real Robert that committed the crime. "It’s feeling to me like I wasn’t there," Gonzales insists, his voice rising in volume and pitch. After more than an hour, he says, "I wish I had my auntie here." Minutes tick by and the high-pressure techniques continue. The detectives say they sympathize with Gonzales, tell him they would be angry, too, if a girl had lied to them about her age. "We all have problems when angry," Sanchez says. And it dawns on Gonzales, nearly two hours in. "Is she dead or what? Is she murdered or what?" he asks, panicking. By now, he’s spent. His voice grows quiet and he begins to mumble some of his answers. "You got pissed the fuck off. You put your hands on her," says Detective Sanchez. "Where did you put your hands on her?""On her neck," says Gonzales. The statement is unsure, almost a question. The detectives ask Gonzales to demonstrate choking on a plastic water bottle, and it’s this moment, including the way he arranges his hands on the bottle, that earns the confession the adjective "chilling" from Brandenburg. "He put his hands up, not the typical way you would choke someone or not how I would think you would choke someone, and arranges his thumbs in a certain way, and that’s exactly where the bruises were on the body," she says. After the detectives have their confession, Gonzales sits in the interrogation room with another officer. Though there’s no way he could know his future, he says he will "end up doing three years in la pinta ." And he will.No Comment

Before the video ends, Gonzales tells the detectives, "I want to make sure. Are you going to do fingerprints on me? That’s what I want to know." He’s convinced fingerprints will get him out if this mess. His instincts are right. He will never be convicted of the crime. On Nov. 22, 2005, 19 days after Gonzales’ arrest, DNA evidence was returned to the Albuquerque Police Department. That’s according to a report by the state Public Defender’s Office. With dozens of samples collected from the crime scene—swabs from Sandoval’s body, items of clothing, her bedding—Gonzales was excluded as a donor. The evidence pointed repeatedly to a person who was not Gonzales. Court records show APD sent samples from other suspects to Identigen, the DNA testing company, that day. A civil lawsuit was filed in District Court on Gonzales’ behalf early this year. The suit names Detectives Marquez and Sanchez along with the City of Albuquerque, DA Kari Brandenburg, and Assistant DAs Bryan McKay and Lisa Trabaudo. Metropolitan Detention Center employees are also on the list of defendants. A trial date has not been set. Damages will be determined by the jury. Christina Romero says she can’t believe there was DNA evidence that, from the beginning, put someone else at the crime scene. Why was Gonzales picked up in 2005 in the first place? According to the transcript of the grand jury proceeding, an adolescent neighbor of Victoria Sandoval’s told police her friend was hanging out with an older guy nicknamed "Old School." Police asked around West Mesa to find someone with that nickname, according to testimony, and school security gave them Gonzales’ name. The neighbor picked Gonzales out of a photo array and identified him as "Old School," prompting his arrest.Because of the pending civil case, APD declined to answer questions about whether detectives receive any training in interrogating developmentally disabled suspects or whether such considerations were put into place after the Gonzales interrogation yielded faulty results."Even as Much as It Hurts. We Believed That."

Ruben Leyva has worked with Youth Development, Inc. for 15 years as the program director at the Fourth Street Outreach Family Services Center. Gang intervention is one of the four programs he facilitates. Through his work with gang-involved, at-risk youth, he met Gonzales four or five years ago, he estimates. "Robert was one of those that was around quite a bit and knew all the staff and associated with all the staff," he says. He describes Gonzales as "extremely helpful" and "always wanting to give more than he took." To this day, he says, his former pupil calls and offers to do landscaping work at YDI. Gonzales was not heavily involved with a gang, according to Leyva, but he participated extensively in YDI activities. In fact, Leyva saw Gonzales the day before Sandoval was murdered and the day after. "There was no change," he says. "No difference." The day after Halloween in 2005, YDI hosted the Urban Ballet Theater from New York as guest speakers. Gonzales showed off his beatboxing skills. Days later, when Leyva heard the news of the arrest, he was stunned. "To be very honest, I called a pastor friend of mine and bawled," he says. "We believed what our police department and our city leaders told us. Even as much as it hurts. We believed that."Leyva says anyone would have known that Gonzales had a mental disability after speaking with him for a while. "He can carry on a conversation. He can talk. He can associate," he says. "But then you see it, like, just hit a point where, OK, he can’t take this conversation any further."Gonzales, he says, behaves differently now that he’s left prison. "He’s much more subdued. He doesn’t look as much angry about it as he is hurt about it. I’ve never really seen him angry.""It Destroys My Body"

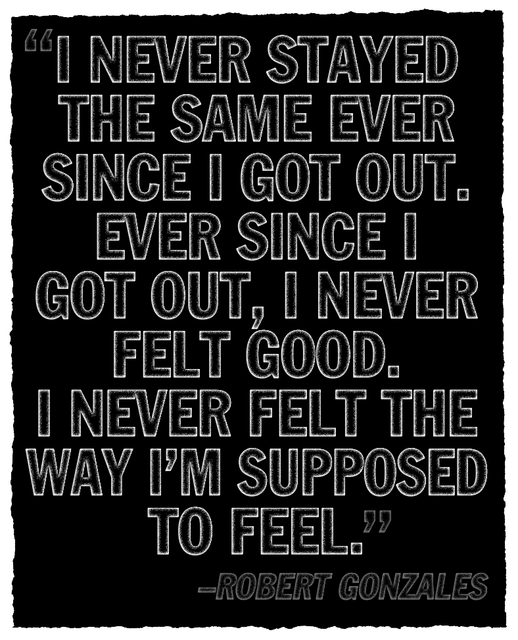

He won’t talk about his confession. He won’t comment on the fact that he spent terrible months in prison while evidence stacked up showing he wasn’t the murderer. "I just hate talking about it," Gonzales says. "It just opens me up, and it hits me. It destroys my body. I never stayed the same ever since I got out. Ever since I got out, I never felt good. I never felt the way I’m supposed to feel."According to jail records, Gonzales’ experience in MDC was fraught with threats, violence and illness. From Nov. 11, 2005, days after he was locked up: "Security reports several verbal threats by other inmates directed at resident due to nature of charges. Resident agitated, tearful, talkative and engaged; says he wants cell by himself." Gonzales complained of violent experiences with guards, according to jail records. He was put on suicide watch as Christmas neared in 2007. "When asked about legal situation, states, ‘I’ve just put that out of my head for now,’ ” says a progress note from that time. While he fought his battles behind bars, his family remained under siege by the media, his aunt recalls. And when he was finally released, Romero says, TV reporters haunted the jail parking lot and jumped all over the family car when they pulled away.Gonzales won’t reflect on some things, like the scholarship he won to a post-high school training program for the developmentally disabled. His time in prison disqualified him from accepting. He looks toward his living room and shakes his head while trying to explain why he can’t talk about it. "He’s locked it up," Romero says."You Can’t Answer a Question Like That"

Though Gonzales was never convicted of killing Victoria Sandoval, and though DNA evidence couldn’t place him at the scene of the crime, he spent 997 days in the Bernalillo County Metropolitan Detention Center. Brandenburg says he was in jail for so long because defense attorney Jeff Buckels raised the issue of Gonzales’ competency. "Everything stops until the defendant is found to be competent," she says. Though APD is shown to have had the DNA evidence six months prior, Assistant DA Trabaudo says the prosecution didn’t receive word of it until the summer of 2006. At the end of 2007, Gonzales’ defense asked that he be released from jail, and the request was denied in March of 2008. Israel Diaz, who lived in the same trailer park as Victoria Sandoval, was arrested for burglary in April and his DNA entered into the system. It was a match for the DNA found at the years-old crime scene where Sandoval’s body was found. Still, it wasn’t until Diaz confessed and said he acted alone that the District Attorney’s Office dropped charges against Gonzales on June 27, 2008. So does Brandenburg believe Gonzales’ confession was false? "That would be very, very simplistic," she says. "You can’t answer a question like that." She says DNA is available in maybe 20 percent of the cases her office prosecutes, and 80 percent of them are considered without it. "To assume we should have known immediately when the DNA was announced that he was innocent—no," she says. "That doesn’t tell us anything." Instead, she adds, it means there was probably someone else involved. When Diaz’ DNA was shown to match, Brandenburg says, prosecutors assumed he would implicate Gonzales. "When he didn’t say that, we knew that we didn’t have enough evidence," she says. "There are a lot of people still involved in the investigation that have questions.""There’s Not a Shred of Evidence"

Attorney Brad Hall will represent Gonzales in the pending civil suit. He says APD and the District Attorney’s Office knew they had the wrong guy in jail from the time they received the DNA. "Robert did not know the victim, and they know that," he says. "There’s not a shred of evidence corroborating what she [Brandenburg] calls a confession."Hall also points out that detectives picked up Gonzales at a special ed facility at West Mesa where he had paused to visit with teachers. They should have known that he had a developmental disability, he says. "All you gotta do is ask a teacher." Hall adds that there’s a mountain of records showing Gonzales has been evaluated by the state since he was a child. "They could just go get those things and look them over before they haul off and call a press conference," Hall says. Brandenburg says in the last eight years, the District Attorney’s Office has handled more than 240,000 cases. "If you put it in context of one in 240 [thousand], do you think that requires a total re-evaluation? I don’t know." Still, she adds, one in 240,000 is one too many. "It behooves us all," Brandenburg finishes, "to try and look at things more cautiously and with a little bit of skepticism and make sure we have a lot of corroborating evidence."*The Alibi was able to view the videos at attorney Brad Hall’s office but does not have a copy in its possession.