Back to the Future

To be sure, steampunk has been part of the cultural conversation for the past several years, as DIY-ers like the Rosenbaums have embraced a handwrought, Steam Age aesthetic over high-tech gloss. Both a pop culture genre and an artistic movement, steampunk has its roots in 19 th – and early-20 th – century science fiction like Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine . Its fans reimagine the Industrial Revolution mashed-up with modern technology such as the computer. Dressing the part calls for corsets and lace-up boots for women, top hats and frock coats for men. Accessories include goggles, leather aviator caps and the occasional ray gun. And there’s a hint of Sid Vicious and Mad Max in there, too.Still, steampunk defies easy categorization. It can be something to watch, listen to, wear, build or read, but it’s also a set of loose principles. It attracts not only those who dream of alternative history, but those who would revive the craft and manners of a material culture that was built to last.First introduced as a literary subgenre, William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s 1990 novel The Difference Engine popularized the idea of an alternate history where the Industrial Revolution-level technology of pistons and turbines, not electricity, powers modern gadgets, as Victorians might have designed them. Even in the ’60s, the television series “The Wild Wild West” helped define the genre. The sci-fi Western featured a train outfitted with a laboratory and featured protagonists who were gadgeteers.Some pop culture genres such as Tolkienesque fantasy imagine a magical past of strange races and global quests. Others, such as hardcore dystopian science fiction, warn against a future marred by apocalyptic meltdown. Then comes steampunk, a hybrid vision of a past that might appear in the future—or a future that resides, paradoxically, in the spirit of another age.No, you’re not stuck in some goofy concept album by The Moody Blues. Steampunk is a fantasy made physical, made of brass and wood and powered by steam, born of a throwback to the Industrial Age. It takes form both as an aesthetic movement and a community, with people manifesting their visions through literature, gaming, film, music, fashion, science, design and architecture.The Techno Revolt

Martha Swetzoff is a Rhode Island School of Design faculty member and independent filmmaker who’s directing a documentary on the subject. “The acceleration of the present leaves many of us uncertain about the future and curious [about] a past that has informed our lives, but is little taught,” she says. “Steampunk converses between past and present.”It also represents a “push back” against throwaway technologies and a “culture hijacked by corporate interests,” she says. You might say steampunk is more akin to the open-source software movement than a retro-futuristic world to escape into. It isn’t about how how fashionable and expensive your toys are, it’s about how cleverly one can create something out of detritus from the discarded past.Steampunk maker and steampunkworkshop.com blogger Jake von Slatt (real name: Sean Slattery) likens the philosophy to the open-source software movement. It’s “drawing on actual history. You can pull into it what you’re into and put your spin on it,” he says. “It’s accessible yet expandable. There is a real focus on sharing, exploring things together, building community.”Mr. von Slatt, who came of age in the era of punk rock, new wave and goth, has always been a tinkerer. He says that steampunk lets him "revisit youthful enthusiasms." Now he creates intricately crafted anachronistic objects: for example, computer keyboards taken apart and rebuilt with brass, felt and keys from antique typewriters. He’s transformed a 1989 school bus into a wood-paneled "Victorian RV,” which he uses to travel to steampunk conventions.Currently, he’s “steampunking” a fiberglass, 1954-style Mercedes kit car, tricking it out with gold filigree trim and salvaged gauges and lights from other cars. Drawn to a “do-it-yourself, making something from nothing” mantra, von Slatt scavenges most of his components from the dump.Such functional art objects tap into a nostalgia for a mechanical (as opposed to electronic) age. Unlike the wireless signals, microwaves and motherboards of today, the 19 th century’s gears, pistons and tubes are visible and visceral. While the workings of a laptop can seem impenetrable, we can fathom the reality of moving parts.Ellen Hagney, executive director of the Charles River Museum of Industry & Innovation, is committed to staying connected to the mechanical world. The museum is a former textile mill in Waltham, Mass., filled with steam engines and belt-driven machines. “As the world becomes more digital,” she explains, “the world less and less appreciates machines, which will be lost.” October through May, the museum hosted Steampunk Form and Function, an Exhibition of Innovation, Invention and Gadgetry. Accompanying the exhibition was a weekend-long convention called International Steampunk City, “a sort of Ringling Brothers meets the Industrial Revolution event” that encompassed the entire downtown area. “We are trying to train a new generation to appreciate this,” she says, “and keep these machines running.”Human Nature

Tom Sepe is one of the artists who exhibited in Hagney’s Steampunk Form and Function show. He shipped his “Whirlygig,” a functioning “steam electric hybrid motorcycle,” from his workshop in Berkeley, Calif. The circus performer discovered steampunk via the Burning Man art community. He says he looks at his life as art. “Every choice we make is part of a performance,” he says. “Every object we make or touch becomes an artifact of who we are and how we have been.”For Sepe, three “crucial” elements keep him engaged in the steampunk maker culture: the “warmth factor” of handmade materials, functionality and “freethinking imagination and fun.” Unlike other art forms, he says, “it doesn’t take itself too seriously.”Whereas other genre fans can niggle over the small stuff, steampunk tends to be more open-ended. Jeff Mach, one of the partners behind New Jersey’s Steampunk World’s Fair, remembers goths back in the ’90s sniping at one another for not being "goth enough.” Not so with this latest, more inclusive cultural mashup. “It’s not starting from a single point but many points,” he says. That may be why steampunk’s reach is exploding, from Boston to San Francisco’s Bay Area, to Britain, New Zealand, Japan and beyond.“Steampunk is definitely growing in popularity,” says Diana Vick, vice chair of Steamcon, a two-year-old convention in Seattle that doubled its attendance in November. “I believe it is due in part to the fact that it is a rejection of the slick, soulless, mass-produced technology of today and a return to a time when it was ornate and understandable.”Every culture that embraces steampunk makes it their own. Patrick Barry, a member of New Zealand’s League of Victoria Imagineers, has seen myriad international examples. “All have a different flavour, world vision and cultural base for the artists and writers to draw from,” he writes via email, “and it shows.” Even in his tiny hometown of Oamaru, steampunk has taken off. Three groups just mounted an exhibition, a fashion show and several other events. “Oamaru has a population of about 13,000 people. We had 11,000 people visit the exhibition” over its six-week run, he says.Some of the most committed steampunkers dress up in period garb and take part in live-action role playing games. Most LARPs (think Dungeons & Dragons but in costume) are sword- and sorcery-based, but Steam & Cinders is one of only a handful of steampunk-themed games, and their ranks are growing.Once a month, some 100 players gather for a weekend at a 4-H camp in Ashby, Mass. The game’s premise? A crashed dirigible has stranded folks at a frontier town called Iron City, next to a mysterious mine. Engineers, grenadiers and aristocrats vie for supremacy. There are plenty of robots to fight (players dressed in cardboard costumes sprayed with metallic paint) and potions to mix (appealing to the mad scientist in us all). Players stay in character for 36 hours straight.Indeed, dedicated steampunkers are lured by fashion. To dress up as a privateer and pilot flying machines powered by “lift-wood,” or to play a scientist who meddles in alchemy, the required accouterments include military medals, parasols and aviator goggles.“Yes, it’s a fantasy world, and it’s not England,” says Steam & Cinders founder Andrea DiPaolo. “But getting to dress in British garb and speak in a British accent is something I enjoy.”“It Wants to Teach Us Things”

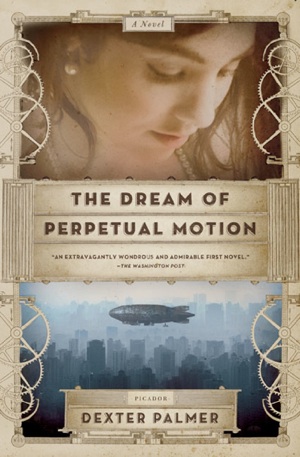

Previously, most works in the steampunk genre would have been set only in the Industrial Age. Over time, explains Dexter Palmer, author of the novel The Dream of Perpetual Motion , the term "steampunk" has undergone “definition creep.” “Nowadays the label’s much more comprehensive,” he says, “and seems to refer to any retro-futuristic or counterfactual work that features machines with lots of gears, or lighter-than-air flying craft, or similar sorts of things.” For example, Terry Gilliam’s dystopian 1985 satire Brazil has been retroactively embraced as part of the genre.In Palmer’s novel, a greeting-card writer who is imprisoned aboard a zeppelin must confront a genius inventor and a perpetual motion machine. The author created a set of rules for his fictional universe: While things might be “scientifically implausible” to the reader, they would be "self-consistent and plausible to the inhabitants of the imaginary world." He based his ideas on source materials that predicted life in the year 2000 and then designed gadgets that seemed modern but used turn-of-the-century tech. One is an answering machine that functions by recording to a wax cylinder.Writers and publishers are striking while the steampunk iron is hot. “We can tap into the enthusiasm of a reader who can imagine an alternative version of the 19 th century,” says Ben H. Winters, author of this summer’s mashup Android Karenina .Winters steampunked Tolstoy’s novel by re-envisioning Anna Karenina in a 19 th -century Russia with robotic butlers, mechanical wolves and moon-bound rocket ships. (Sample line: “When Anna emerged, her stylish feathered hat bent to fit inside the dome of the helmet, her pale and lovely hand holding the handle of her dainty ladies’-size oxygen tank.”)“Hopefully, we’ll be adding to the fandom of the mashup novel by introducing a new fan base: the sci-fi crowd,” says Winters, who also wrote 2009’s Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters. “One of the really wonderful things about Steampunk,” Jake von Slatt writes on steampunkworkshop.com, “is that it, more than any other subculture, seems to want to teach us things.” And, like the punk and goth movements before it, what’s being taught is another way of looking at the world.Steamcon’s Diana Vick adds that another appeal lies in its largely optimistic and romantic—not dark and cautionary—outlook. “We also embrace and foster good manners and dressing up,” she says, “which are both sorely lacking in society today.”Bruce and Melanie Rosenbaum aren’t particularly into costuming, but they break out period garb when attending an event. They say they love turn-of-the-century fantasy but, Bruce says, “you don’t want to live in the 19 th century in terms of conveniences.” That’s why they retrofit modern appliances or hide them behind facades of functional art.Climb to Bruce Rosenbaum’s third-floor study and you’ll enter a world of a sci-fi/Victorian mashups. The attic space feels like a submersible, packed with portholes, nautical compasses and a bank vault door. His computer workstation desk is ornate and phantasmagorical, ringed with pipes from a pipe organ. It’s a place where you can imagine Captain Nemo banging out an ominous dirge. Or the ghost of Jules Verne hammering out a few emails.“How much more fun is it to make something ornate and beautiful, rather than boring and unadorned?” asks Melanie. “There’s freedom with steampunk. … Almost anything goes.’”With freedom come vast stores of potential. Steampunk could be the next goth, or even bigger. “I think this is the beginning of steampunk as a new sort of thing, as a pop culture phenomenon,” says von Slatt. “I think it’s the tip of the iceberg.”Calling All Steampunkers!

steampunkworkshop.com

steampunkworkshop.com

A version of this article appeared in The Christian Science Monitor.

Ethan Gilsdorf is the author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms (Lyons Press). He contributes regularly to The Boston Globe, New York Times, National Geographic Traveler and The Christian Science Monitor.