Red, White And Black

Being Black In Albuquerque In A Post-Obama World

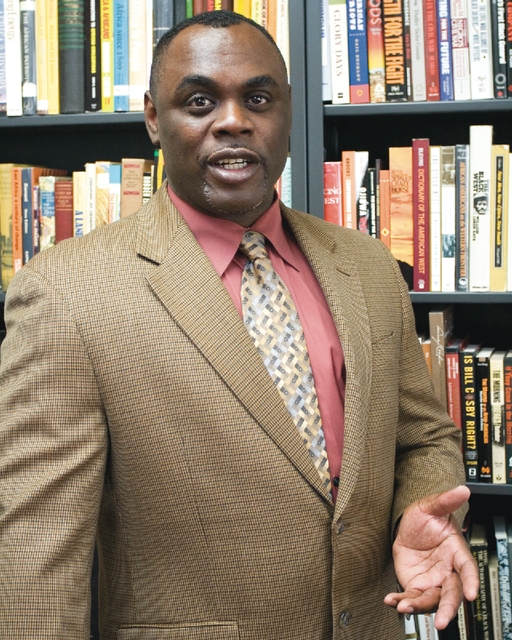

“For people who operate on grassroots levels, there’s a tremendous amount of hope. They’ve been vindicated in some ways.” —Dr. Jamal Martin

Eric Williams