The Tragedy

The KiMo Theatre was successful for its first quarter century, but tragedy waited in the wings, striking just before 4 o’clock on Thursday, Aug. 2, 1951. According to accounts in the Albuquerque Journal and Albuquerque Tribune , about a thousand people were in the theater to see the Abbott and Costello film Comin’ Round the Mountain when a water heater exploded into the lobby. Chunks of plaster, scalding steam and glass shot into the air. When the dust and chaos settled, eight people were injured; several were treated for fractured arms and legs, and one man lost an eye. Tragically, the most seriously (and fatally) injured was Robert (Bobby) Darnall Jr., a 6-year-old boy. Bobby had gone to the theater with two friends, 11-year-old Lou Ellen and 7-year-old Ronald Ross. The trio sat in the balcony watching This Is America: They Fly with the Fleet , a 16-minute short documentary about U.S. Naval Aviation Training. Bobby became frightened by a loud siren in the film and ran from the balcony, Lou Ellen in pursuit. The boiler under the stairs exploded just as Bobby entered the lobby, his head and face crushed when the blast hurled him into a wall.Bobby’s funeral took place the following Saturday morning at Fairview Park Cemetery. He stayed at rest—according to KiMo Theatre receptionist Jewel Sanchez, in Antonio Garcez’ book Adobe Angels: The Ghosts of Albuquerque —until that “one Christmas Day in 1974.”Bobby’s Return

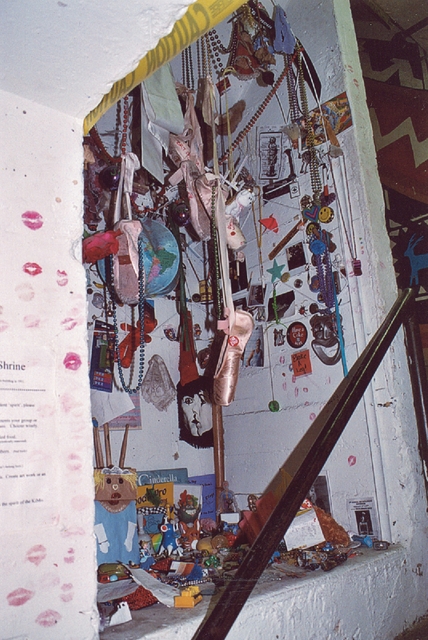

“It was just before Christmas, and the New Mexico Repertory Theater Company did A Christmas Carol ,” Dennis Potter, the KiMo’s longtime technical manager, explained. The director, Andrew Shea, noticed some doughnuts strung up against the brick wall at the back of the stage, supposedly left as an offering to Bobby’s ghost. Shea ordered them removed, a decision he and the cast would soon regret. Potter, who was there that fateful night, explained: “About 10 or 15 minutes into the show, weird things started going wrong. … People were forgetting their lines, people were tripping and falling on stage, odd pieces of equipment would fall from the ceiling, light bulbs exploded. Electrical cables fell down … light gels came off and fluttered down during dramatic moments … windows and doors on the set were either not opening or were opening when they weren’t supposed to. It was just really weird. They almost literally didn’t get through the show, there were so many disruptions.”Finally, somehow, the disastrous show concluded. According to Potter, the director replaced the doughnuts. With the doughnuts returned, the ghost agreed not to ruin the next show, and indeed it went off perfectly without so much as a dropped line. From then on, as long as performers left doughnuts for Bobby, performances went fine. The doughnuts eventually gave way to a more extensive shrine in a nook beneath the stairs to the dressing rooms—an altar still filled with toys, notes, photos, cheap jewelry, ballet slippers and so on. Some say an actor who forgets to leave something for Bobby puts the entire play at risk. According to some sources, Bobby continues to haunt the KiMo and has ruined other performances since. Writer Scott Johnson claims, “For a period of time, it seemed that not one performance went off without some type of disaster. … Sightings of Bobby are continuous, year round.” There are a few other reports of people seeing—or experiencing something attributed to—Bobby’s ghost, though none are detailed enough to investigate. The story of the KiMo Theatre has all the elements of a good ghost story, including the tragic death of a young boy and mysterious and unexplained happenings. Yet all the reports—true or not, and absent further investigation—are simply stories and anecdotes, not hard evidence.Enter the Ghost Hunters

Albuquerque ghost hunters Ron and Sherri Andree, along with their group New Mexico Paranormal Investigations (NMPI), claim to have found evidence of Bobby’s ghost in the decorated halls of the KiMo. The NMPI team has appeared on television several times in regard to the KiMo story, including on KRQE Channel 13 in an award-winning feature segment broadcast Halloween 2007. The NMPI team conducted a one-night investigation, searching for evidence of Bobby or other spirits. It used cameras, electromagnetic field (EMF) detectors, dowsing rods, thermometers and other equipment. Investigator Sherri Andree added, “We thought about what a 6-year-old from the ’50s would like to play with, so when we did our investigation we brought him a baseball and some Silly Putty.” It’s a sweet thought, though it’s not clear how a disembodied spirit without human hands would play with a baseball or Silly Putty. During the investigation, NMPI reported finding “anomalous EMF energy,” a “wisp of energy” and so on, as well as taking photographs it claims are of Bobby’s ghost.Cody Polston, the founder of another ghost-hunting group, the Southwest Ghost Hunter’s Association, also looked into the KiMo ghost story. The description in his book Haunted New Mexico contains a few accounts of Bobby, “who has been seen playing on the stairs leading to the balcony. He is described as having brown hair, wearing a stripped [sic] shirt and jeans.”… But Is It True?

At first glance, the evidence that Bobby Darnall haunts the KiMo Theatre seems impressive. Eyewitnesses saw unexplained, seemingly paranormal poltergeist phenomena during the ruined Christmas production (and later plays); ghost experts confirmed the existence of something supernatural at the KiMo, complete with “anomalous” photos. But one dictum of skeptical investigation is, “The devil is in the details.” In this case, the ghost is in the details—or isn’t. The disastrous Christmas Carol production is key to understanding the KiMo ghost story, for several reasons. It is the first time Bobby Darnall’s ghost was linked to mysterious occurrences at the KiMo. Perhaps more importantly, it is something tangible, something that can be verified. Most of the “evidence” for ghosts consists of odd feelings, ambiguous photos and occasional sightings—things that can’t really be examined or tested. But the unexplained exploding lights, mysterious falls and objects moving on their own—witnessed by thousands of people on several occasions—is much closer to hard evidence. Something —whether Bobby’s ghost or some other mysterious force—supernaturally ruined the production of A Christmas Carol on Christmas Day, 1974. Or did it? The first step in unraveling the mystery was verifying the date. According to several sources (including Garcez, in his book Adobe Angels ), the doomed production was held on Dec. 25, 1974. Yet there was no production of A Christmas Carol on that date at the theater. In fact, a newspaper archive search revealed that the KiMo was at that time an adult theater and patrons that day saw a pornographic film called Teenage Fantasies . (The tagline was “If ‘ Throat’ made you tingle, this will make you twitch!”) If Bobby was present that day, the early ’70s porn was probably more disturbing to the child ghost than the lack of doughnuts. Potter, the eyewitness, instead placed it sometime in the late ’80s or early ’90s; his memory was hazy about not only the year but the decade. With some detective work, we narrowed down the year to December 1986, then contacted others involved with that production of A Christmas Carol . We spoke to Steve Schwartz, the actor who played Bob Cratchit, and asked him what he remembered about that fateful night. “It went great, it was a wonderful performance,” he said. A wonderful performance? With all the forgotten lines, exploding lights, props mysteriously moved by unseen hands, actors tripping onstage and so on? Schwartz replied, “That sounds like good copy, but I can’t corroborate any of that. I don’t remember any problems like that, or any problems with the show.” The technical manager and an actor in the same play had two completely different memories of the show. Of course, people’s memories change over time, and though Mr. Schwartz didn’t recall problems with the play, someone else might. To get a third eyewitness account, we contacted Andrew Shea, who directed the play and whose dismissive doughnut disposal allegedly led to the ruined performance. Shea, now a film director with a 2007 feature called Forfeit , spent eight years directing plays at the KiMo, from 1984 to 1991. He also disputed Potter’s recollection: “I don’t remember it being a disaster in any way,” he said. Furthermore, according to Shea, the story of him taking down the doughnuts and then replacing them after the disastrous performance never happened. He also discredits other stories about ongoing strange occurrences at the KiMo: “There were no events during my eight years there that didn’t have mundane explanations. … I don’t recall anything supernatural or out of the ordinary happening.” So the play’s supporting actor and the director both discredit the ghost story. A final nail in the coffin comes from newspaper accounts of the play. Surely such a mysterious and infamously disastrous performance would have been noted in the Albuquerque Journal or the Albuquerque Tribune reviews. Instead they were positive; not one mentioned any problems or the events Potter described. All the evidence points to one inescapable conclusion: The ruined play—the very genesis of the KiMo ghost story—simply did not occur; it is but folklore and fiction.Spawning the Story

Where does this leave Dennis Potter and the countless articles his tale spawned? Potter is not a liar, nor is he crazy; he simply did something we all do from time to time: He made a mistake and misremembered. Decades of psychology research show that human memory is remarkably fallible. The brain is not, as many suppose, a sort of tape recorder that accurately preserves what we experience. Instead, memories change over time. Until and unless we are confronted with evidence to the contrary, we will continue to confidently believe our memories. (For an excellent discussion of memory mistakes and how false memories can be created, see books such as Memory , by Elizabeth Loftus, and Brain Fiction , by William Hirstein.) Psychology helps explain how Potter’s faulty memory could create a ghost story. But hundreds of sources, from Antonio Garcez to Albuquerque ghost hunters to local television reports and websites, repeated the story of Bobby and the doomed show. How could every account have gotten it wrong? The simple answer is that Potter is the sole source of virtually all the information. The journalists, writers and “investigators” just repeated the stories, never bothering to check the facts. In fact, most of the information on the KiMo ghost exhibits shockingly sloppy research and even outright plagiarism. For example, ghost hunter Cody Polston, founder and president of the Southwest Ghost Hunter’s Association, heavily plagiarized a book chapter on the KiMo ghost. Nearly half of a two-page entry on the KiMo ghost from a 1999 book called Haunted Highway: The Spirits of Route 66 is lifted verbatim (and uncredited) in Polston’s 2004 book Haunted New Mexico. With so many authors simply copying each other’s work instead of doing any actual research, it’s little wonder errors are repeated and myths are taken as fact. If they can’t be bothered to do their own research, they certainly can’t be trusted to do a credible investigation. There was indeed a tradition of hanging doughnuts at the KiMo, but Potter says it started when someone would get coffee and doughnuts for the cast and crew. “Usually an extra cup of coffee or doughnut would be left at the end of the day,” Potter explained. “As a joke … we’d take the doughnut and tie it up on the electrical conduit on the back wall. … It was a souvenir collection, an oddball history of the building.”Ghostly Evidence

With some investigations and a few pointed questions, the story of Bobby Darnall’s ghost collapses like a haunted house of cards. But an obvious question arises: What about the ghost hunters who claimed to find evidence of Bobby’s ghost? What phenomena at the KiMo are they interpreting as evidence of the paranormal? To answer this, some background on ghosts and ghost hunting is helpful. First, despite decades of searching, no one has yet found hard evidence of life after death or spectral visits. Instead, ghost hunters accept a far lower standard of evidence than scientists and skeptical investigators do.Much of the “evidence” provided by the NMPI investigators about the KiMo consists of vague feelings, senses and impressions. According to the report, “A team member had a very uncomfortable experience in the basement area. … ‘I felt a huge sense of sadness. … I felt so sad that I wanted to just start crying.’ ”Is this evidence of a ghost? Or is there another explanation? The problem is, of course, that these feelings cannot be independently or scientifically verified; there’s no test for a “sense of sadness.” They can, however, be explained by psychology and the power of suggestion: Just because a person has a panic attack doesn’t mean the perceived threat is real. (A friend of mine with an anxiety disorder had panic attacks when he crossed bridges; his fear, sweating and racing heart were real, but the threat to him was all in his mind.) In the same way, if a ghost hunter is convinced that he or she is in a room with a scary, angry ghost, that person will likely have experiences similar to those the NMPI staff describe—even if no ghost is there. Most ghost hunters realize their personal feelings are neither good science nor good evidence, and therefore they use more reliable tools and equipment. On the face of it, this is a step in the right direction, from subjective feelings to objective measures. But the problem is that the science and methodology don’t necessarily improve with better gear. For example, many ghost hunters (including the NMPI) use dowsing rods when searching for ghosts, conveniently ignoring the fact that dowsing rods have never been proven to find ghosts. NMPI, along with the Southwest Ghost Hunter’s Association, also uses digital thermometers, digital cameras and electromagnetic field (EMF) detectors—again, none of which has been shown to find ghosts. Aside from a few “anomalous readings” from the EMF detectors, one of the NMPI’s favorite pieces of evidence for ghosts is something called orbs. These are “unexplained” round or oval white shapes that appear in photos and are claimed to be ghosts. Orbs may seem otherworldly because they appear only in photographs and are usually invisible to the naked eye. They are often unnoticed when the photo is taken; it is only later that the presence of a ghostly, unnatural, glowing object is discovered, sometimes appearing over or around an unsuspecting person. In fact, many ordinary things can create orbs, including insects, reflected flashes and dust. To those unaware of alternative explanations, it’s no wonder that orbs spook people. (For more on this, see Benjamin Radford’s article “(Non)Mysterious Orbs” in the September/October 2007 issue of Skeptical Inquirer magazine or Kenneth Biddle’s book Orbs or Dust ?) The ghost hunters made another mistake. The NMPI website has a short write-up of its investigation, and one photograph shows an orb at the top of the KiMo’s stairs; the caption reads, “Note orb at location of Bobby’s death.” However, Bobby Darnall did not die on the stairs, as the NMPI investigators claim. According to a photo and caption on page 2 in the Aug. 3, 1951 Albuquerque Journal , “Balcony stairs directly over the heaters were undamaged.” Since the stairs above the heater were “undamaged,” it’s virtually impossible Bobby was on the stairs (much less on the landing where the “ghost photo” was taken) when the explosion occurred. Had Bobby been on the stairs, the concrete stairs themselves would have shielded him from the blast underneath. The ghost hunters are even wrong on a more basic point. In what is perhaps the final irony, not only did Bobby Darnall not die on the staircase where his supposed ghost was photographed, he didn’t even die at the KiMo Theatre! According to the Aug. 2, 1951 Albuquerque Journal , Bobby Darnall was alive when he left the KiMo: “Police said the boy had a faint pulse when picked up in the theater lobby, but he was dead on arrival at St. Joseph’s Hospital.” So Bobby actually died in an ambulance somewhere on the streets of downtown Albuquerque. Just as Potter did not intentionally create the story of the KiMo ghost, the ghost hunters did not intentionally hoax or mislead anyone with their EMF readings and orb photos. Their “evidence” is simply a series of misinterpretations and mistaken assumptions. To be fair, the low level of science is typical for amateur ghost hunter groups nationwide. They are staffed by sincere people with good intentions but a poor understanding of investigation, research or scientific methods. Perhaps most troubling, such ghost hunting organizations portray themselves as experts and authorities on ghosts and the paranormal. They sell books, give lectures and charge money for seminars, supposedly teaching people how to conduct ghost investigations.Death of a Legend

The inescapable conclusion is that there is simply no evidence of a ghost at the KiMo Theatre. Ultimately, the KiMo ghost story is not a lie nor a hoax—but it’s also not true. Faulty memories and poor research created the KiMo ghost when combined with standard theater ghost lore and some misguided ghostbusters. The story spread, told and retold, hashed and rehashed, each iteration adding or omitting details without anyone bothering to check the facts until finally a ghost was created. The KiMo ghost has been the subject of local lore for at least a decade. While some may mourn the passing of a good ghost story, no harm can come from learning the truth. Only when the KiMo story is acknowledged as fiction, not fact, can the memory of little Bobby Darnall truly rest.Benjamin Radford is a longtime scientific paranormal investigator and author of three books and hundreds of articles on critical thinking, investigation and mysterious phenomena. He has investigated, and solved, many ghost cases, including the Santa Fe Courthouse Ghost mystery in 2007. In his purely imaginative spare time, he also writes and directs films and created a board game called Playing Gods. His websites are RadfordBooks.com and PlayingGods.com.

Mike Smith is a researcher and author of Towns of the Sandia Mountains . He writes for many publications, including New Mexico Magazine and Local iQ , and has a website at MyStrangeNewMexico.com.