The Land Of The Dead: Forgotten History At Fairview Cemetery

Forgotten History At Fairview Cemetery

A memento left on Deborah Ernice Bauer-Fout’s grave by her daughter.

Ty Bannerman

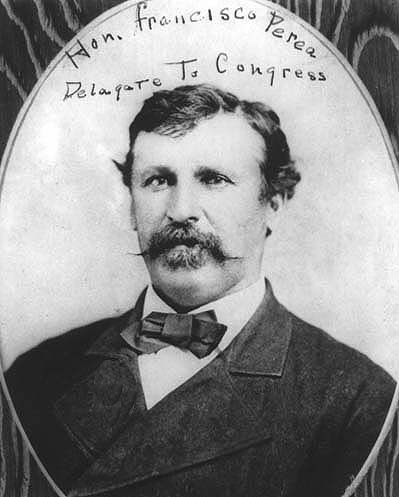

Francisco Perea defended Albuquerque during the Civil War and fought in the Battle of Glorieta Pass.

Suffragette and Congresswoman Ruth Hanna McCormick founded Sandia Prep and Manzano Day School.

Fairview, Albuquerque’s oldest public cemetery, has suffered from years of neglect.

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com

This monument marks the site of Fairview’s earliest recorded burials.

Eric Williams ericwphoto.com