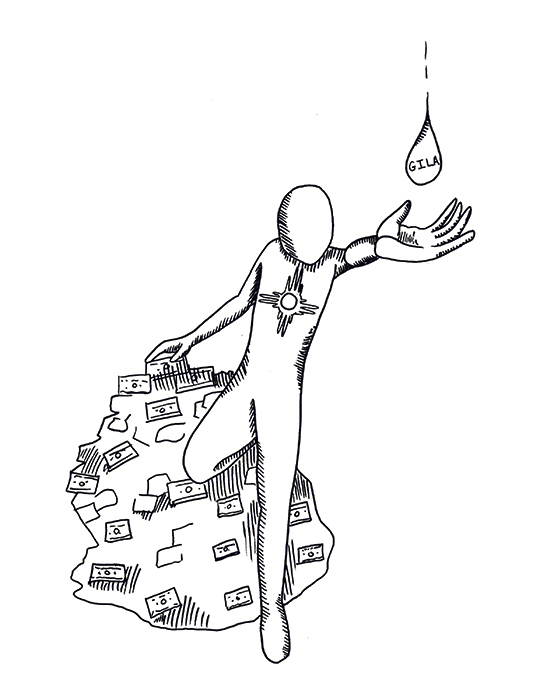

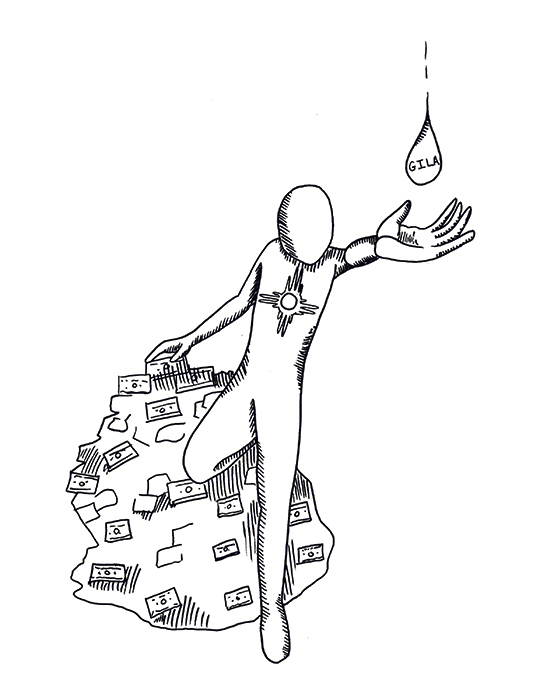

The Last Wild River

Gila River Diversion Project Seeks To Secure Water For New Mexico At Any Cost

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992