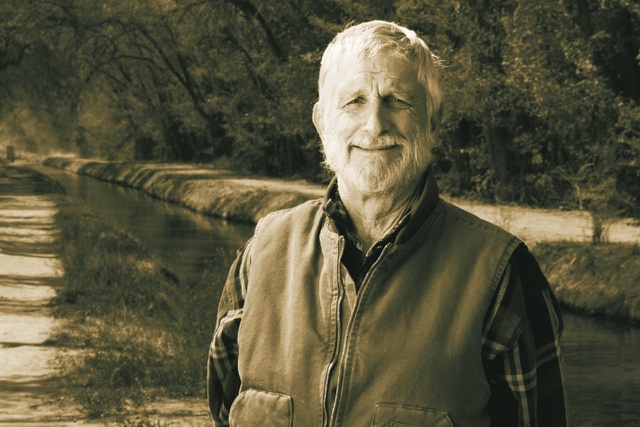

Before germ theory and the sanitary practices that resulted, doctors were mystified about the role of microorganisms in infection and death. The idea of hand-washing was controversial. Surgical procedures were performed in unseen filth. Years from now, an ignorance similar to the kind exercised in antiquated medical practices might be blamed for modern society’s treatment of its environment. Since the World War II era, New Mexico—once a place where people were sent to recover from illness—has been infiltrated by toxins. Much of the pollution can be attributed to the corporate and military entities that colonized the state. The laws of ecology dictate that everything has to go somewhere. In New Mexico, waste materializes in Santa Fe’s drinking water, polluted by trace amounts of radioactive runoff from Los Alamos National Labs. Or a plume of chemicals spreads beneath the Albuquerque’s South Valley, deposited by GE, Chevron, Texaco and others. In his book The Orphaned Land: New Mexico’s Environment Since the Manhattan Project , veteran Albuquerque journalist, poet, novelist and teacher V.B. Price exposes the state’s toxic legacy as a means of safeguarding the future. Price, who moved from Los Angeles to attend UNM as a freshman in 1958, spent seven years writing a tome that tells a regional history of a careless, contentious and complicated modern age. Over breakfast in the North Valley, Price discussed a few of the subjects tackled in The Orphaned Land . How was the Manhattan Project a turning point in New Mexico’s environmental history? New Mexico had been a health center. It had been a mining center too, but mining was still relatively primitive compared to what it is today. It was also the home of three profoundly responsible agrarian communities—Pueblo, Navajo and Hispanic—who understood how to take care of the land, who were almost genius at the capacity to save water, to grow things in a place where nobody could grow them. So the sense of the land, and what we did with it, and how we operated on it, was very refined here. Then suddenly, here comes the Manhattan Project, and along with it an enormous amount of national industry. [It] didn’t care about New Mexico, didn’t care about our agrarian traditions, didn’t care about the fact that we were a health center with beautiful, clean air and clean water. We had this war to win. You point to a fictional New Mexico as an allegory for the one we’re living in today. When I discovered that New Mexico was in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World —the Savage Reservation where all the misfits and outcasts went and were locked behind a huge electrified fence—I thought, My God, this is the metaphor for a state that has been turned into a sacrifice zone by the military, by the mining industry, by the oil and gas industry. Not that we don’t need all of these things, but you don’t have to make a living and win wars by ruining the place that you do it in. So, while we’re not actually walled in, I think our national image is of a place that doesn’t really matter very much because it’s empty, and it’s filled by weird people who don’t really matter very much either. I think that’s the way we’re looked upon, which of course is the furthest thing from the truth yet. How do classism and racism factor in? It’s important to know it’s not just New Mexico. What is the simplest place to dump your trash? On poor people. In places where there is rudimentary infrastructure that you can use and a population that nobody cares about. There’s between 650 and 1,000 open pit or underground uranium mines on the Navajo, Laguna and Acoma Reservations west of Albuquerque. Most of them have never been reclaimed. The Navajos were basically a cancer-free society until uranium mining. Everything about uranium mining is contested: “Do you think this is dangerous?” “No, I don’t think it is.” “Yes it’s dangerous!” “Is it dangerous?” “No, it’s not dangerous, don’t worry about it.” “Of course it’s dangerous, my kids are dying over here!” And on and on and on and on. It’s terribly cynical and terribly normal. What creates these situations? Socrates said a long time ago that nobody thinks they’re doing wrong. I do think that’s true. I think the key thing is the view that the ends justify the means. The ends of profit have justified in the past tremendous sloppiness when it comes to waste. Are you hopeful? I am. I’m hopeful for a number of reasons. I’m a grandparent: I can’t afford to be unhopeful. I’m hopeful because of what human beings can do if they want to. What can individuals do to help? One, you can associate with any number of dozens of environmental groups. Two, you can learn about conservation; you can learn what to do with your own trash. Three, you can educate yourself. In an information age when the Internet has virtually anything you want to know—even about this stuff—it’s a sin not to educate yourself. It’s not even that hard to do anymore. What’s your main message? Basically that we have been careless in the past. We’ve caused ourselves a tremendous amount of trouble that we’re going to have to solve in the future, and that we can solve it. … I really tried very hard to not make this a depressing book. The subject matter is depressing, but it’s not a doom and gloom thing at all. I think you can’t solve problems unless you know the problems exist.

The Orphaned Land: New Mexico's Environment Since the Manhattan Project By V.B. PriceUniversity of New Mexico Press, paperback, $29.95