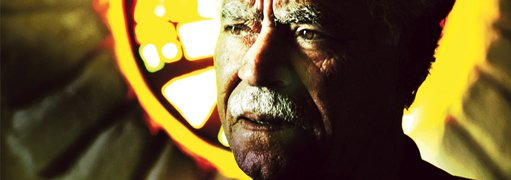

He’s hardly a stranger to censorship. Just inside the doorway of Rudolfo Anaya’s cozy Westside home is a white cardboard box. It’s full of articles documenting instances when his landmark Chicano novel Bless Me, Ultima was suppressed. “Every time it’s banned, a fellow writer calls me up and says: Hey great! Wish I could get all that publicity you’re getting.”Sales increase, he says, and libraries can’t keep Ultima on the shelves.“But the problem is real, of course, that there are people who still think their way is the only way.”On Jan. 1, Arizona dismantled Tucson’s Mexican American Studies program. This prompted schools to pull books associated with that curriculum from classrooms. Included were Ultima and The Anaya Reader . Also yanked were works by Sherman Alexie, Sandra Cisneros, bell hooks and scores of others. The Tempest by William Shakespeare made the hit list, too. “It’s a struggle,” Anaya says. “Since the Chicano movement started and we were writing contemporary literature, there was this backlash. It may be stronger than ever because of this extreme conservative political mindset.”It’s been a long battle, and it doesn’t look like it will be over anytime soon.In 2010, Arizona lawmakers passed HB 2281, which outlaws courses that are deemed to:• promote the overthrow of the United States government• promote resentment toward a race or class of people• be designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group• advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individualsTom Horne, then the superintendent of public instruction, championed the bill because of ethnic studies classes taught in the Tucson Unified School District. Horne argued that these courses divided the students—Asians studying Asian studies, etc.—“just like the old South.” He was particularly concerned with the Mexican American Studies program, though, charging the lesson plans and textbooks were not approved by the school board and teachers were getting carried away with their message. Courses taught historical inaccuracies, he alleged, and widened racial divisions.John Huppenthal took Horne’s post in 2011. He posited on June 15 that the Mexican American Studies program remained in violation of the new law. At the end of the year after several hearings, Judge Lewis Kowal ruled it was within Arizona’s rights to withhold 10 percent of state funding from the region’s schools. Huppenthal ordered the Tucson district be denied millions, so the school board voted to do away with the program. As part of the curriculum’s demolition, certain books were boxed up and put into storage.Arizona doesn’t exist in a vacuum, Anaya says, and we have to be concerned about close-mindedness cropping up within our state lines, too. “Quite frankly, they’re bigots, and they exist everywhere,” he says. “We have to be vigilant, and we always have to fight against censorship, any kind of censorship.”He digs through the files, searching for one article in particular that appeared in the Albuquerque Journal in late February 1981—more than 30 years ago. It’s about a measure in the New Mexico Legislature that aimed to set standards for schoolbooks. Sen. Christine Donisthorpe (R-San Juan) announced during a hearing that the Bloomfield School Board ordered Bless Me, Ultima to be burned. Donisthorpe was a member of that school board. She’s quoted as saying members personally ensured copies of the novel were lit on fire. Ultima , set in rural New Mexico, had been used as part of a cultural awareness class in Bloomfield, N.M.Since the burning was in his home state, “that was the most traumatic,” says Anaya. “That’s pretty extreme dictatorship.”Novels are often rooted in place and culture, he says. “Haven’t we always read the Southern writers? Don’t we study the early New England writers? Of course we do. So why shouldn’t we read the literature of the Southwest?”When young people know the language, literature and art of their culture, it gives them a sense of identity, he explains. “Once you have a sense of identity, you then can compete in mainstream culture,” he says. “But if you are lacking that sense of identity, you are more apt to give up and drop out.”He says he can imagine how the students in Arizona must have felt after the school board sent the message: This literature is not worthy of study. “It’s telling them, You are not worthy.”The study of culture profits all students regardless of ethnicity, he says. “We have to live together. Isn’t knowing about each other better than not knowing? Resentment and prejudice come when we don’t know.”A Houston group called Nuestra Palabra is aiming to run “wet books,” or contraband literature, back into Arizona. Tony Diaz, who’s leading the charge, has been in contact with Anaya, and the Librotraficante Caravan will stop at his house for a meal while in Albuquerque.In the end, Anaya says he trusts Ultima will be back on Arizona’s classroom bookshelves. In every instance of banning filed away in his cardboard box of suppression, folks wouldn’t stand for it. “The good people of the community will come back and say, We want our kids to read all sorts of literature because that’s the way of a democracy.”

Librotraficante Banned Book BashThursday, March 15, 7 p.m. National Hispanic Cultural Center 1701 Fourth Street SWlibrotraficante.com