If you’re like me, you spend a reasonable amount of time navigating this burg in a petro-fuel-powered vehicle. Often, such devices contain other devices lodged inside of them, including various forms of radio wave reception equipment that can be interfaced with for listening purposes whilst one drives.Election season provides an opportunity for various individuals and organizations to add to the mix of DJ banter, familar tuneage and commercial call-outs for everything from the latest in sleeping systems to fantastic footwear technology too good to ignore—all meant to be absorbed for later consumption by car-bound customers who have their ears in the air.The additional, election-age information usually takes the form of campaign and issue endorsements or deconstructions. While our eight lucky candidates for mayor have yet to hit the airwaves in a substantive way, the calls for and against the Healthy Workforce Ordinance are already adding weight to mornings otherwise filled with the scatological humor of radio personalities known by handles like “The Hoff,” as well as comfortable-as-old-shoes-songs like “Motoring,” by Night Ranger.The ads I’ve heard so far support the ordinance—an initiative that started as a public petition and has been advanced by our City Council. Those adverts and the bill proposal itself are sponsored by several local progressive and worker-centered nonprofits. The radio spot in question speaks to the working class of Albuquerque through the use of familiar language and situations. In one such announcement, an obviously fraught mother with a familiar Burqueña accent and word usage fusses over her sick daughter, lamenting the fact that she can’t take time off to care for the child.While the repeated use of the term mija and its derivatives are emotional inducements guaranteed to play well to a specific audience, it’s important civic business to take a look at the ordinance—and what the culture that customarily uses such loaded phrases faces when they become too ill to attend to their work day duties.It’s no Arcadian myth that the proletariat lacks in sick leave benefits. For example, my neighbor Todd lives next door in his mother’s house; he’s in his late 40s. He works at a local auto mechanic’s shop. For the past week, Todd has been ill with a kidney infection—I know this because my wife has been bringing him chicken soup—and has not been able to make it to work. His boss knows the facts and his job is in solid standing, but he’s not getting any income in the interim and it shows.A shoulder-to-the-wheel member of the working class, with a predilection for heavy metal music, sci-fi television and a late model Toyota SUV that beats the hell out of my ‘85 Volvo, Todd’s become anxious and listless as his health slowly improves. Bills are going unpaid—with a salary of $80 per day, he’s afraid he’s going to get behind quickly and might have trouble procuring groceries, dog food and gas as a result. Of course such workplace-related stress just contributes to his malaise and many in the public health field agree that such stress further prevents or delays employee health and readiness.And he’s not alone, Todd is one of a growing number of Americans who have jobs that do not provide much in the way of benefits, including the ability to accrue and use sick leave hours to be paid by the company—unless the government mandates such. When such employees get ill, they not only miss out on sustained productivity at their workplace, but their personal and familiar economies also suffer grieviously. Neither the business nor the individual benefit in such cases.Asking the city administration to regulate this situation seems to be the essence of what government was designed by the founders to do; providing for the general welfare of citizens ultimately means a healthier, more able and more adaptable workforce.As it stands the proposed ordinance has seen stiff legal challenges from some members of the local business community who feel that it will ultimately undermine profitability, preventing owners from trickling down excess plata they might otherwise use to pay a living wage, hire more employees or buy that awesome 2018 Escalade just sitting there on the lot. As it stands, the proposal—all seven pages of it—will appear on the Oct. 3 ballot.The proposed legislation has been criticized for featuring labyrinthine language and demonstrating an anti-business sentiment. It’s important that each citizen voter read through it beforehand and decide for themselves. In an ironic twist, the ordinance has been most succinctly summarized by local employment attorney Jeremiah L. Ritchie, who wrote:“The proposed ordinance, if approved by voters, would require that employers provide accrued paid sick time of one hour for every 30 hours worked. This would apply to all employees that work a minimum of 56 hours per year, whether they are seasonal, temporary, or part-time. The leave may be used for a wide range of mental or physical health-related absences, including the illness of a family member.”I don’t know about you, mijitos y mijitas, but that sounds pretty damn good to me; those who argue otherwise run the risk of looking like craven capitalists at a time when our city and nation crave leadership imbued with a sense of shared purpose and moral responsibility. To be clear, providing for the health of our citizens through this ordinance is the first step in re-humanizing government services and business practices. To do otherwise would unfairly defer the economic well-being of all parties involved. Once problems like public and employee health and welfare are rectified, other issues that seem out of reach—like failed education systems, pervasive poverty and consequently crime—may be easier to fix as well.

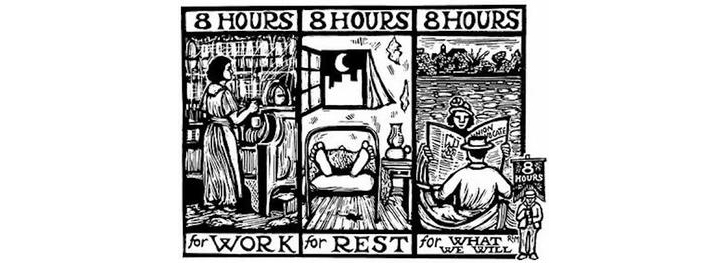

The City of Albuquerque Municipal Election:Tuesday, Oct. 3, 2017Early Voting takes place between Sept. 13 through Sept. 29