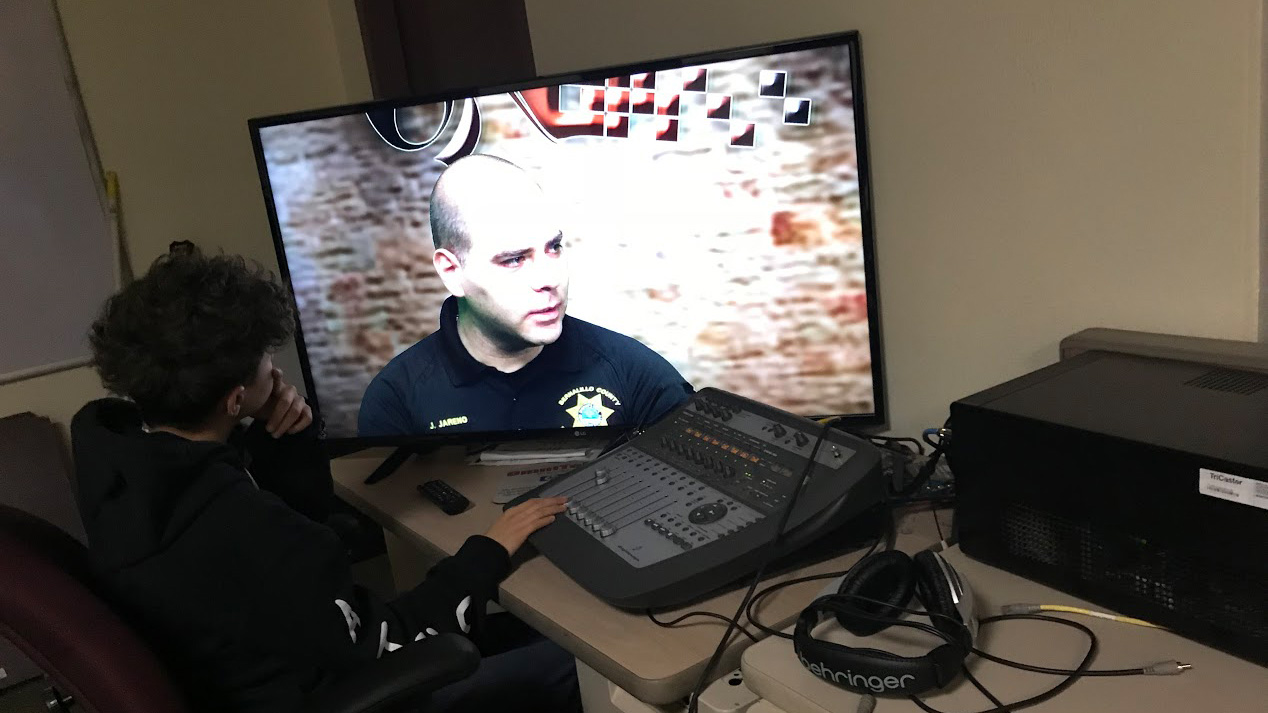

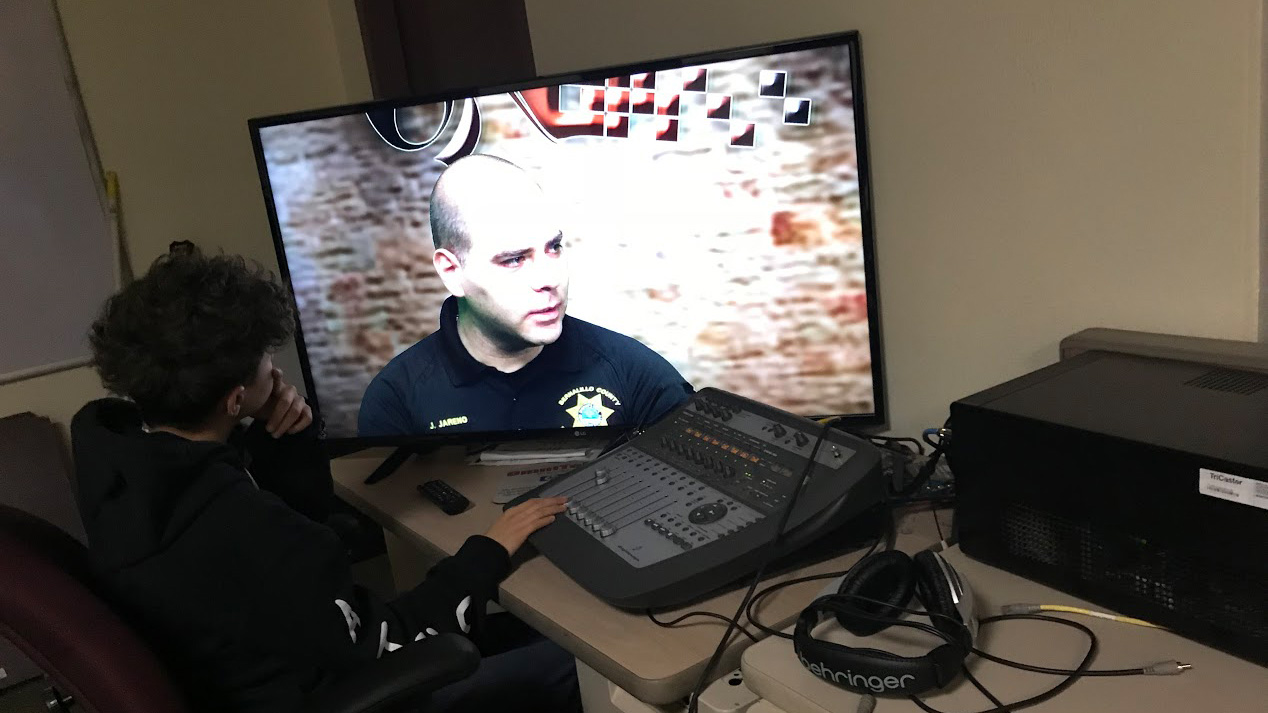

Editorial: A Path To Community Policing

Teaching Children And Officers Works

At MACCS with BernCo Sheriffs

Anthony Conforti

Latest Article|September 3, 2020|Free

::Making Grown Men Cry Since 1992

At MACCS with BernCo Sheriffs

Anthony Conforti