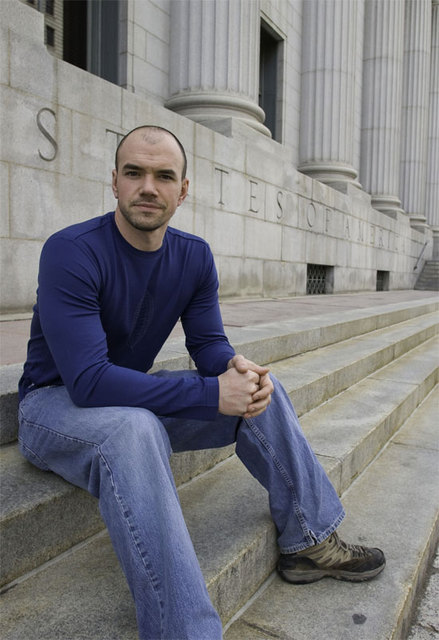

Tim DeChristopher walked into the oil and gas lease auction without a plan. It was December 2008, and 27-year-old DeChristopher was a university student and climate activist. The Bureau of Land Management was planning to sell the drilling rights to vast parcels of land during the last days of Bush’s presidency. It was the culmination of eight years of work by the Bush administration, DeChristopher says, a "brief window where the oil industry had everything it wanted." So the parcels were larger than usual and closer to national parks than ever, he explains. DeChristopher’s determination to really do something had been building. For years, he’d been riding his bike and writing letters and speaking to his congressional representatives. "I felt like my actions were not to the scale of the crisis," he says. When he got to the BLM auction, someone asked him if he wanted to be a bidder and handed him a paddle. "And I said, Yes." With that, DeChristopher became bidder 70.He started out easy. "I would wait for it to get down to one bidder, and I would drive it up for a while and then get out before I actually won anything." In just minutes, he would cost the oil companies tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars. But he decided he could be doing more—so he started winning every parcel. He claimed 22,500 acres of drilling rights in Utah that day. "Once I started doing that, I felt totally calm. I had a real feeling of peace come over me." DeChristopher is part of the climate justice movement, which has a different approach than what we’ve come to know as environmentalism. Climate activists don’t want a cleaner, greener version of the world we have now, he says. "That would still be a world filled with injustice. We’re not necessarily interested in making some big corporations a little more environmentally friendly." At times, the two movements are at odds. Environmentalists approach their work by appealing to the power structure that’s in place, he explains, and climate justice folks want to see that structure change. His movement is also more concerned about the impact of climate change on people, he says. "I don’t know that I would ever got to jail to protect plants or animals." In March, DeChristopher was found guilty on two felony counts related to interfering with the auction. He’s considering an appeal after his sentencing on Thursday, June 23. He could face up to 10 years in prison but has heard that, considering the sentencing guidelines, the prosecution is seeking about four and a half years. Were you surprised by the verdict? No. Not at all. Why not? What tipped you off? The jury wasn’t able to hear a lot of key information. They weren’t able to hear that this auction I disrupted was later overturned when the government admitted it was illegal in the first place. They weren’t allowed to know that I raised the money and offered it to the BLM after the auction, and the BLM refused to take it. I think the biggest factor for me was how intensely the jury was instructed that they were not allowed to use their conscience. It was really reinforced to them over and over by the judge that their job wasn’t to decide if this was right or wrong. They weren’t allowed to question whether or not the law they were enforcing was just. Even though you knew it was coming, how did it feel when you were convicted? Within a few hours afterward, it felt a little bit like a relief. … Once I finally got that verdict, I just kind of felt like: Now I can move on to the next stage, which I’ve already been preparing for for a while. So, jail time is becoming more real. It’s certainly scary, and it always has been. It seems to be the kind of thing that the closer it gets, the less scary it becomes. I have a good idea of where I would be sent to. I’ve been able to read the handbook, and I’ve seen the daily schedule. That makes it very real, to know exactly what I’d be doing each day. Not to sugarcoat it, but I certainly think it’s something that I can handle. Is there a list of things you’d like to accomplish before you go in? There’s some very basic stuff. I’ve got to sell my car and things like that. The last couple years, I’ve been trying to make sure that the momentum of this action would not be lost and that the impact of it would be something lasting.I’ve been working on this organization [Peaceful Uprising] that I built shortly after the auction. That’s really becoming a powerful force now and growing into its own and developing some strong leaders. That’s certainly been encouraging to see. I’ve been spending my time since the trial speaking to as many folks as I can, and trying to empower as many people as I can, to take action and helping them to get on that path. How long have you been working on environmental justice? I’ve been a full-time activist for two and a half years since the BLM auction. Before that I was very focused on environmental issues and climate change in particular. Those kind of issues have always been a big part of my life. Growing up in West Virginia, my mom was an activist fighting the coal companies in the early days of mountaintop removal in the early ’80s. So it’s always been a part of my life and values that I’d been brought up with. Is your mom proud of you? For a long time her sense of pride for me was dwarfed by her fear of what was going to happen to me. During the trial, she was speaking to one of my friends, and it was the first time she ever said it was worth it for me to go to jail. I think she’s been gradually coming to terms with the consequences that I will have to face, but she has been supportive throughout the whole process. What can really be done about climate change from an activist’s standpoint? We can prepare for it, is where we’re at now. We’re in a really interesting time as a movement. That’s part of why the climate justice movement has been emerging as a distinct force—because there’s a growing awareness that it’s probably too late for any amount of emissions reductions to prevent some sort of collapse of our industrial civilization. What that means is that we’ll be navigating through the most intense period of change that we’ve ever seen, or perhaps, that our civilization has ever seen. When you consider the future that we have on the horizon, it becomes very important who’s in charge and who’s calling the shots. …It’s not just about reducing emissions anymore, but it’s about defending our humanity through whatever difficult times lie ahead. That’s why we’re seeing two separate movements today. There’s one movement that’s still primarily focused on emissions reductions and that sort of thing. And there’s one that’s at least as focused on building the kind of power structures and communities to hold onto our humanity through ugly times. You’ve said that costing the fossil fuel industry money is the only way to change its behavior. How can people do that? Getting in their way I think is the biggest thing. But ultimately I don’t think it’s about convincing the fossil fuel industry to change its behavior. I think it’s about overthrowing the fossil fuel industry, kicking them out of our political system and having a political system that’s driven by human beings. When you look at innovation, it’s rare that any individual or organization that was responsible for one big level of innovation was responsible for the next level. There were no carriage companies that became car companies. There were no typewriter companies that became computer companies. We can say, “Oh they’re not necessarily fossil fuel companies. They’re energy companies, and they could just as well be clean energy companies.” That’s nice, but it’s not realistic. When you look back, has it been worth it? Absolutely. My mindset at the time was a very direct-action mindset. You know, If I can keep this oil in the ground, then it’s worth it. That part of it has happened. … The new administration overturned the auction and kept those parcels protected. The action also inspired others and catalyzed this public discourse about what our role as citizens should be when our government is acting illegally. I think that could prove to be more important than just protecting those parcels. Even for me, the personal impacts are something I never really expected. I went into it with this sense of necessity, that I had to act and that it was worth it to make these sacrifices. What I’ve seen since then is that it’s also really liberating, that it actually has felt good to be in this position. It made me a more contented person to be firmly resisting the path that we’re on. There’s been kind of this healing process for me that makes it worth it, as well.

A talk with Tim DeChristopherPresented by New Energy EconomyMonday, June 13, 6 p.m.Greer Garson Theatre Center University of Art and Design1600 Saint Michael’s Drive, Santa Fe$10 suggested donationpeacefuluprising.orgbidder70.org