Baseball: Making Claim To A Foul Ball Is Seldom Easy

Making Claim To A Foul Ball Is Seldom Easy

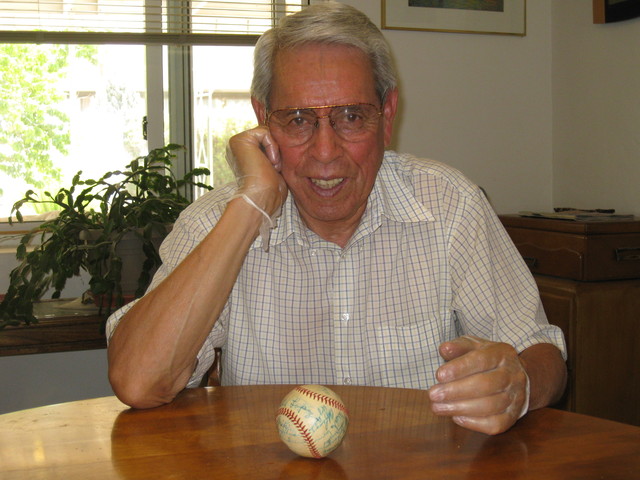

Art Duran

Toby Smith

Toby Smith

Toby Smith

Fans at Isotopes Park get ready for a game

Toby Smith